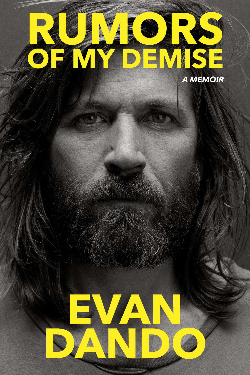

Coincidentally, in tandem with Lemonheads frontman Evan Dando’s new memoir, Rumors of My Demise (Gallery Books), I’m also reading David Lee Roth’s 1997 tell-all autobiography, Crazy from the Heat. Both are packed with salacious stories about the indulgent lifestyles of these in-the-right-place-at-the-right-time musicians, these boy wonders living Peter Pan lives and seemingly escaping consequence with ease. But surprisingly, it’s only Roth who writes with remorse, humility, and wisdom.

Coincidentally, in tandem with Lemonheads frontman Evan Dando’s new memoir, Rumors of My Demise (Gallery Books), I’m also reading David Lee Roth’s 1997 tell-all autobiography, Crazy from the Heat. Both are packed with salacious stories about the indulgent lifestyles of these in-the-right-place-at-the-right-time musicians, these boy wonders living Peter Pan lives and seemingly escaping consequence with ease. But surprisingly, it’s only Roth who writes with remorse, humility, and wisdom.

That’s not to say that Dando’s book isn’t without merit or endless entertainment. With a ghostwriter in tow (perhaps just someone who transcribed Dando’s fanciful stories as he told them while supine on a couch), the prose is not as lucid nor poetic as I’d expected. After all, in my mind’s eye, Evan Dando was the archetypal grunge icon, a loquacious storyteller, and the cut of his jib made me a lifelong devotee to the Lemonheads’ best work. It’s a Shame About Ray belongs on the ‘90s Mount Rushmore with Nevermind, Ten, and Siamese Dream. He was a statuesque Adonis figure, and much to his chagrin, the face of what is now considered “bubblegrunge.” Truly, most of the joy in reading his memoir is in the details of his songwriting and recordings. The Lemonheads’ streak with Atlantic Records is pure gold. But for Atlantic, gold wasn’t enough—they wanted Nirvana numbers.

Dando’s knack for effortless melody and simple three-chord pop was unparalleled. That was something that probably propelled him through life from a young age. No reader is going to relate to the silver spoons childhood spent on Martha’s Vineyard or in TV commercials, or at a prestigious arts high school. There’s also little empathy for the “trenches” the Lemonheads had to endure to eventually make it to MTV and a major label deal. They’re that rare band that toiled for years in the tail of Boston’s mid-punk comet (they were referred to as “sweater-punk” in the local press) to come out of the other end ready for the changing musical landscape. Yet, in those times, Dando was already battling addiction and a paralyzing sleepwalking demon that follows him throughout the story.

Drugs are a focal point, particularly heroin, which Dando tosses around like it’s weed, though we all know it’s not. They fuel all of the charmed adventures (a jovial LSD jaunt into the scaffolding around Atlantic with Johnny Depp ) and the unbelievable misadventures (Dando and Gibby Haynes wrecking Depp’s Porsche in pursuit of crack) that this seemingly lost soul escapes unscathed. There are also several incidents in which Keith Richards plays codependent to Dando’s discrepancies. Yet, as many times as rehab is mentioned in the text, Dando seems content living a life on some kind of reality-numbing substance.

Kurt Cobain also hangs like a ghost in Dando’s memory and pulls away from the nonchalance of the narrative. Dando seems hung up on believing Cobain killed himself thinking that Evan was in a relationship with Courtney Love (Kurt’s wife). Here’s where Rumors of My Demise comes unhinged, or at least a bit sensational. Certainly, Cobain projects a wide shadow on a similar face-of-a-generation figure like Evan Dando, but in surviving decades now, Dando should have moved past that trauma. He hasn’t learned how to articulate whatever pain he has but yet makes mentions of all of the priceless sweaters he inherited in Cobain’s death.

Still, it’s those dichotomies that make Rumors of My Demise worth reading and an excellent portal into a time that doesn’t have much self-reflection or crucial criticism. I had the pleasure (or perverse pleasure) of seeing the Lemonheads in 2025. Dando, apparently sober, laboriously sang through Ray and Come On Feel the Lemonheads, but throughout he would stop, play an oblong cover, tell a nonsensical aside, switch guitars a few times, then wander backstage to get a kiss from his current partner. He genuinely showed humility that a sold-out crowd still wanted to hear his songs. As the show veered past two hours, it embodied everything that makes Dando a complicated genius. Which is kind of what his book tries to tap into: the fact that we all contain multitude versions of ourselves.

Your Comments