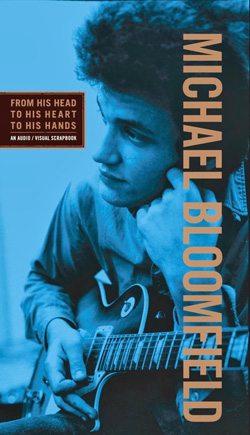

One doesn’t have to go too far out on a limb to say that Michael Bloomfield is underrated. For many music fans—even those who are relatively well versed in the music of the ’60s and ’70s—Bloomfield is simply the guy who played lead guitar when Bob Dylan went electric at the Newport Folk Festival. The fact is, though, that Bloomfield produced a wealth of recorded material during his short lifetime that stands alongside the best blues music made during that time period. Some 33 years after Bloomfield’s death, From His Head to His Heart to His Hands (Columbia/Legacy), an excellent boxed set compiled by Al Kooper, goes a long way toward doing justice to Bloomfield’s legacy.

One doesn’t have to go too far out on a limb to say that Michael Bloomfield is underrated. For many music fans—even those who are relatively well versed in the music of the ’60s and ’70s—Bloomfield is simply the guy who played lead guitar when Bob Dylan went electric at the Newport Folk Festival. The fact is, though, that Bloomfield produced a wealth of recorded material during his short lifetime that stands alongside the best blues music made during that time period. Some 33 years after Bloomfield’s death, From His Head to His Heart to His Hands (Columbia/Legacy), an excellent boxed set compiled by Al Kooper, goes a long way toward doing justice to Bloomfield’s legacy.

The set, which contains three CDs and one DVD, begins with three songs from Bloomfield’s 1964 audition with Columbia Records’ John Hammond Sr. Accompanied only by a bass, Bloomfield’s lively performance indicates his early mastery of the blues. The feisty “I’ve Got You in the Palm of My Hand” and “I’ve Got My Mojo Workin’” represent Bloomfield’s early recorded work for Columbia, backed by friends from the fertile blues scene in his hometown of Chicago. Bloomfield’s contribution to Dylan’s Highway 61 Revisited is recognized via two previously unreleased tracks that will be a treasure to Dylan fans: a revelatory instrumental version of “Like a Rolling Stone” and an alternate version of “Tombstone Blues” featuring the Chambers Brothers on backing vocals. Rounding out the first disc is a number of selections from Bloomfield’s two best known bands, The Paul Butterfield Blues Band and The Electric Flag. The former’s “East-West” features a lengthy and choice display of Bloomfield’s sonic fireworks, while the latter shines with a version of “Killing Floor” that’s equal parts rollicking and scorching.

The second disc consists of material from the Bloomfield/Kooper Super Session collaboration and the series of concerts the two men staged in the wake of that album’s release. Bloomfield’s playing on the slow blues of “Albert’s Shuffle” and the horn-augmented “Stop” is amazingly expressive, and there is great interplay on “His Holy Modal Majesty” between Bloomfield and Kooper, who plays the Ondioline electronic keyboard on the song in an attempt to mimic John Coltrane. Keeping in the Super Session mold, the live tracks and covers of “59th Street Bridge Song (Feeling Groovy)” and “The Weight” capture Bloomfield at his best. He adapts perfectly to whatever mood the ensemble pursues, and his ability to switch from rabid blues playing to jazz-tinged licks is unparalleled. These songs also occasionally feature Bloomfield’s often-overlooked vocal skills, and his sultry lead on “Mary Ann” is particularly noteworthy.

Following the Super Sessions period, Bloomfield retreated from the spotlight, disillusioned with the record business and battling personal demons. Disc three of the set chronicles the last 12 years of Bloomfield’s life, during which he sporadically played low profile shows and contributed to friends’ recordings. He made a great sideman as witnessed on his complementary playing on Janis Joplin’s “One Good Man” and Muddy Waters’ “Can’t Lose What You Ain’t Never Had” and his sizzling leads on a handful of tracks recorded with Electric Flag vocalist Nick Gravenites in 1969. But Bloomfield also retained the ability to be a compelling frontman, as heard on solo songs recorded during a live appearance in New York in 1977. His country blues playing and singing is excellent on “Darktown Strutters Ball,” and he showcases his playful side to an appreciative audience with “I’m Glad I’m Jewish.” Just three months before his death in February 1981, Bloomfield had the opportunity to reunite with Dylan when his former collaborator made a tour stop in San Francisco. The set chronicles that moment with a recording of Dylan’s “The Groom’s Still Waiting at the Altar.” Bloomfield is on fire, and Dylan sounds like he’s charged by his old friend’s energy.

The film Sweet Blues rounds out the set and features extensive and insightful interviews with Bloomfield’s friends, bandmates, and family that give a nuanced look into the man behind the guitar. Highlighting the hour-long film are two impressive live performances, one a slide-acoustic solo rendition of “He’s a Dyin’ Bed Maker” filmed near the end of Bloomfield’s life, and a frantic and blistering excerpt from The Electric Flag’s set at the Monterey Pop Festival. The film fittingly complements the music on the set, and the entire package makes a strong case that Bloomfield may, in fact, have been the best guitarist of his generation.

Your Comments