Once proto-punk finally became regarded as “a thing,” it was too little, too late. The ’77 punk movement had ignited into a raging inferno, engulfing every square inch of rock & roll’s corpse, entrails and all, as if it were attempting to rid a crime scene of any DNA or fingerprints. Although not immediately felt, the emergence of punk signaled that the end was nearing for album-oriented rock and its card-carrying fleet. The seismic shift in the underground, instigated by the likes of The Stooges and the MC5 at the dawn of the ’70s, was far too great for any Sabbath or Zeppelin leviathan to withstand. If rock & roll was supposed to be about rebelling, then punk must have equated to mass murder. The vileness and savagery and filthy stench that dogged the Sex Pistols were sheer evidence of this changing of the guard. They were rock & roll processed through a meat grinder, and Johnny Rotten was the one pulling the levers. Not even disco, which at the time was enjoying an upsurge in popularity in the music charts, was fireproof from punk’s angst. The dominos were starting to topple. People were pissed off, crying out for a regime change, and for good reason. Rock & roll, although “punk” by definition in its earliest stages, had now become an overly corporatized, predictable gimmick that was about to have its fucking head lopped off.

Once proto-punk finally became regarded as “a thing,” it was too little, too late. The ’77 punk movement had ignited into a raging inferno, engulfing every square inch of rock & roll’s corpse, entrails and all, as if it were attempting to rid a crime scene of any DNA or fingerprints. Although not immediately felt, the emergence of punk signaled that the end was nearing for album-oriented rock and its card-carrying fleet. The seismic shift in the underground, instigated by the likes of The Stooges and the MC5 at the dawn of the ’70s, was far too great for any Sabbath or Zeppelin leviathan to withstand. If rock & roll was supposed to be about rebelling, then punk must have equated to mass murder. The vileness and savagery and filthy stench that dogged the Sex Pistols were sheer evidence of this changing of the guard. They were rock & roll processed through a meat grinder, and Johnny Rotten was the one pulling the levers. Not even disco, which at the time was enjoying an upsurge in popularity in the music charts, was fireproof from punk’s angst. The dominos were starting to topple. People were pissed off, crying out for a regime change, and for good reason. Rock & roll, although “punk” by definition in its earliest stages, had now become an overly corporatized, predictable gimmick that was about to have its fucking head lopped off.

While punk rock, as unorthodox as it always was, had retained a sense of catharsis and urgency up until this point, something happened when it swept through the South Island community of Dunedin, New Zealand, at the tail end of the ’70s. At this stage, punk 101 had already infiltrated the NZ landscape to the north in Auckland, as groups such as Proud Scum, Toy Love, the Terrorways, and the Suburban Reptiles helped spawn a vibrant music scene that emulated the loud-hard-fast of Iggy and his Detroit-rockin’ minions. To the south, however, a much different monster was taking shape, as the Dunedin ilk, while open to the insurgence of punk’s venom, was just as in touch with their pop-leaning inclinations as well. Launched by a Christchurch record store manager named Roger Shepherd in 1981, Flying Nun Records ushered in what would become recognized as the so-called “Dunedin Sound,” a mix of lo-fi experimentation with jingle-jangle guitars and Velvet Underground–inspired pop minimalism. Of the earlier bands that emerged from this scene, The Pin Group and The Clean have often been pinpointed as the harbingers of this sound, however, it wasn’t until the release of an untitled quadruple EP in 1982 that everything really started to fall into place for the budding label.

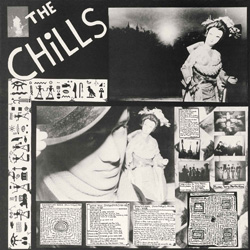

Often referred in name to by its unofficial title, the Dunedin Double, its release introduced the world to four unknown bands at the time: The Chills, The Sneaky Feelings, The Stones, and The Verlaines. While the dent initially made by the album was quite modest when first released to the listening public, it managed to capture a sound that was authentic and native to its surroundings, much the same way Rough Trade did in the UK, and in later years, Sub Pop, with the Pacific Northwest music scene. Recorded on a portable four-track over a two-week period by Chris Knox (Toy Love, Tall Dwarfs) and Flying Nun producer and technician Doug Hood, the lo-fidelity of the songs is in a more dim and overcast vein in comparison to the material that some of these bands (namely The Chills and The Verlaines) would go on to release further down the road. On the surface, a song such as “Kaleidoscope World” by The Chills is a classic Flying Nun song. Although a tad lackadaisical in comparison to a “Heavenly Pop Hit” or a “Pink Frost,” the nuts and bolts that held all of these songs together and made them so memorable in the first place—the shuffling pop hooks, the jingle-jangle guitars, and the singsong choruses—are clearly in the mix . The same goes for the contributions from The Verlaines, whose skewed pop formula has provided no shortage of lasting influence either. Opening up their album side with the chugging, off-beat “Angela,” the band stumbles through the three-minute plus song with sloppy fast-strummed guitars before catapulting into the smeared pop of “Crisis After Crisis” and “You Cheat Yourself of Everything That Moves.”

On the other end of the scale are the two lesser-known bands that anchor this album, the first being the Sneaky Feelings. While not widely viewed at the forefront of the Flying Nun banner the same way The Chills and Verlaines are, the sheer talent and influence this band has had upon the Dunedin music scene should not be diminished. Led by Scottish native Matthew Bannister, the music of the Sneaky Feelings was much more in tune with heroes from the ’60s like The Beatles and The Byrds than anything remotely punk rock, although this blueprint didn’t differ much from anything The Chills or Verlaines were doing around the same time. The song “There’s a Chance” can easily be mistaken for a Verlaines’ song, with its sweeping, psychedelic guitar melodies and somewhat melancholic vocal delivery, while the driving “Backroom” bridles with a dose of trebly fuzz and crisp drum beats.

And then there’s The Stones, a little-known band in the Flying Nun universe. whose own contributions to the label, while minimal in terms of numbers, supersedes their longevity as a functioning band. Featuring the late Wayne Elsey, who would later go on to form the equally short-lived DoubleHappys, the three-piece offers up four songs that are more on par with the primitive post-punk of Roy Montgomery and The Pin Group. The songs are shrouded in a dark, echo-laden atmosphere from the gloomy pop of “Something New” to the tribal thump of “See Red.” “Surf’s Up” sounds like the band channeling Television, with spidery guitar lines that turn and twist and hi-hat snatches that pop and click around thick barbs of bass, while Elsey croaks and sneers like Tom Verlaine.

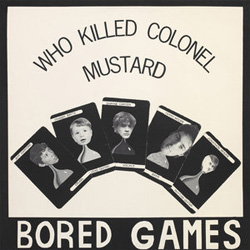

The Stones were never meant to be together for very long, which is probably why the handful of recordings they managed to lay to tape during their brief existence leave a lot to be desired. This can also be argued when discussing the Bored Games, a fellow NZ band, whose then 17-year-old singer, Shayne Carter, would eventually become an integral player in the Dunedin scene first with Elsey in the DoubleHappys, before moving onto the Straitjacket Fits and Dimmer in the late ’80s and early ’90s. Formed while the band’s members were still attending high school in 1979, the Bored Games’ sound was rooted in Ramones-styled gutter punk riled with chainsaw guitar rhythms and 1-2-3-4 song tempos—you know, typical teenage shit. After splitting in 1981, Flying Nun issued the band’s only recording a year later. Titled Who Killed Colonel Mustard, this four-song EP, which features the slapdash gusto of “Bridesmaid” alongside the unnerving brattiness of “Happy Endings” was reissued once again with the Dunedin Double by Flying Nun for Record Store Day last month. In recent years, the iconic NZ label has re-released albums from the likes of the Bird Nest Roys, The Bats, Snapper, Skeptics, and The Clean, amongst others. Let’s hope they keep this tradition alive.

The Stones were never meant to be together for very long, which is probably why the handful of recordings they managed to lay to tape during their brief existence leave a lot to be desired. This can also be argued when discussing the Bored Games, a fellow NZ band, whose then 17-year-old singer, Shayne Carter, would eventually become an integral player in the Dunedin scene first with Elsey in the DoubleHappys, before moving onto the Straitjacket Fits and Dimmer in the late ’80s and early ’90s. Formed while the band’s members were still attending high school in 1979, the Bored Games’ sound was rooted in Ramones-styled gutter punk riled with chainsaw guitar rhythms and 1-2-3-4 song tempos—you know, typical teenage shit. After splitting in 1981, Flying Nun issued the band’s only recording a year later. Titled Who Killed Colonel Mustard, this four-song EP, which features the slapdash gusto of “Bridesmaid” alongside the unnerving brattiness of “Happy Endings” was reissued once again with the Dunedin Double by Flying Nun for Record Store Day last month. In recent years, the iconic NZ label has re-released albums from the likes of the Bird Nest Roys, The Bats, Snapper, Skeptics, and The Clean, amongst others. Let’s hope they keep this tradition alive.

Your Comments