To be a student on the campus of Kent State in the mid-70s must have been a heady time. Post–National Guard snafu, hippie idealism turned to cynicism and the seeds of dissent (or the birth of punk nihilism) were quickly being sown. Classic rock virtuosos were still the vanguard, but experimentalists in fusion and prog were making headway. Within spitting distance of Kent, scenes were taking shape in Akron and Cleveland that would change the course of music (at least within the underground) forever. If you were lucky enough to be a Golden Flash back then, it’s likely you caught 15-60-75 at one of their resident gigs on Water Street. These were indeed “gigs,” as they were first and foremost a bar band. It was hard blues and rambling rhythmic workouts that composed the foundation for the Numbers Band, as they became lovingly better known, though that was just a starting point for leader Robert Kidney. In this microcosm of strong counterculture, they became a nexus connecting eras.

To be a student on the campus of Kent State in the mid-70s must have been a heady time. Post–National Guard snafu, hippie idealism turned to cynicism and the seeds of dissent (or the birth of punk nihilism) were quickly being sown. Classic rock virtuosos were still the vanguard, but experimentalists in fusion and prog were making headway. Within spitting distance of Kent, scenes were taking shape in Akron and Cleveland that would change the course of music (at least within the underground) forever. If you were lucky enough to be a Golden Flash back then, it’s likely you caught 15-60-75 at one of their resident gigs on Water Street. These were indeed “gigs,” as they were first and foremost a bar band. It was hard blues and rambling rhythmic workouts that composed the foundation for the Numbers Band, as they became lovingly better known, though that was just a starting point for leader Robert Kidney. In this microcosm of strong counterculture, they became a nexus connecting eras.

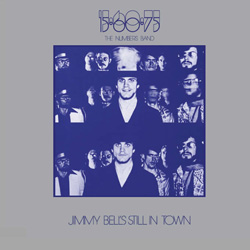

To call Jimmy Bell’s Still In Town (Exit Stencil Recordings) a missing link in rock’s progression is not hyperbole, it’s just the years the album has sat unheard have actually given it that much weight. There were studio attempts into the ‘80s and beyond, but none of it touches the mania and chaos of the Numbers Band’s live repertoire, which still lives today. The Numbers were a band’s band, prescient in sparking impressionable youth to form Devo, The Pretenders, and Pere Ubu, but managing to be an entity unto themselves and rarely straying outside of Kent. They embraced all sounds, sounding like everything at once, yet resembling none of it.

Perhaps that’s why Jimmy Bell, their lone live document, has remained a lost treasure for so long. It’s sheer singularity and inherent “otherness” is hard to grasp, unless of course, you were there. The 1976 performance was recorded at Cleveland’s legendary Agora Theater in front of a crowd eagerly anticipating headliner Bob Marley. The Numbers play long, sinewy, sinister grooves. The title track alone goes through 13 minutes of Kidney doing his best Lou Reed/Robert Johnson runs while the band reaches an incendiary peak. There are no hooks, no choruses, just endless searching and freedom. In retrospect, there were very few groups of the era to dabble in such a total musicality—maybe the Dead, maybe Zappa—finding pathways in which to include jazz skronk , heavy psychedelia, and Bo Diddley. The brass was likely a sticking point for some. Enter the room when the saxes of Tim Maglione and Terry Hynde (Chrissie’s brother) were on blast and you’d think it was the J. Geils Band signed to ESP or Chicago on a brown-acid bender. Give it some time and they become indispensible, an element of drama and action that propels these jams. The same can be said for Michael Stacey’s guitar work. While Kidney steeps the songs in a monotone bluesman call and response, which is equally blunt, acerbic and poetic, Stacey dodges it all with both lysergic leads and proto-punk thrift. If the Numbers had a nucleus, it was Stacey’s playing. Nowhere is that balance more noticeable than on the ouroboros cycle within “About Leaving Day.” Before this deluxe reissue, which includes the entire concert, this was the finale, with Kidney proclaiming, “If it gets hard to feel, It gets hard to love,” a fitting couplet for the band. It wasn’t so much that you “get it,” what mattered was getting into it.

Your Comments