Wexner Center, Columbus, October 10

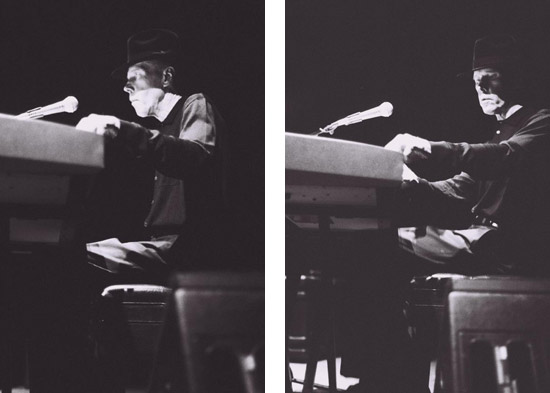

by Michael P. O’Shaughnessy (text and photos)

Sometimes things have a way of just working out. A month ago, Jandek was a complete mystery to me. Only a few times in passing had his name come up, and one day a recording of his Your Turn To Fall album appeared. A couple of weeks after that his name started appearing in the papers advertising a show at The Ohio State University’s Wexner Center for the Arts. Surely there was more to this enigmatic artist than the desperately skeletal, spectral crooning over atonal pluckery that fills the aforementioned album if the man was scheduled to play at such a prestigious artistic institution. Perhaps this was providence, a sign, an opportunity. The man alone in my headphones would be live on stage, and perhaps the less I knew going into it the better. But the signs and whispers didn’t stop; at another show it was revealed that low-power FM deejay, punk-racket musician, and former club owner Adam Fleischer, on a whim, contacted Jandek in the hopes of playing live with him, and Jandek instead took Fleischer’s suggested local musicians and pieced together a band. Ryan Jewell would be playing percussion, local jazz et cetera session man Derek Dicenzo playing the bass, and Cincinnati noise maven C. Spencer Yeh would be playing who knows what for Jandek. Going into the show oblivious was quickly becoming impossible, as this was much more of an event than previously let on. Derek Dicenzo, a consummate professional, is known for his incredibly skilled but not quite restrained improvisation. Ryan Jewell unabashedly digs everything to which he can invent a rhythm (that is to say, everything), and C. Spencer Yeh is said to make even the most mundane sets he sits in on transcendent. Would there be any room for that lonely sound in the headphones? More importantly, would they even be able to speak the same language?

This tentative pastiche of musical styles converging inside the Wexner Center (in the midst of a giant, internationally coveted Andy Warhol exhibition, no less) raised questions of high art versus low art, the DIY aspect of impulsive noise music versus the academic improvisation of jazz all colliding with the solipsistic sound of Jandek plunking a guitar alone in a room. This was to be a truly singular experience.

Inside Wexner’s Black Box performance space, designed like a top shelf recording studio, the possible idea of an environment of dirty punk DIY ethic disappeared. Two keyboards were set up on stage left, drums opposite on stage right. In between were a bass cabinet with an Echo-Plex on top and an array of effects pedals next to strange metal and cardboard cylinders and a violin. The room was nowhere near packed, but the 75 to 100 people there focused intently as Jewell raked his modified violin bow on the rim on his rack tom, back and forth, cultivating a creak and groan through his kit. The rest of the band kicked in raucously, as a unit, as if they’d been playing together for months instead of the few hours they’d jammed for earlier in the day. Dicenzo melded with Jewell’s rhythm, emitting a throbbing subsonic low end as Yeh squealed away on his effected violin. Jandek (should we call him Sterling?) simply and deliberately keyed his organ, pulsing the low keys along with the band through the physically arresting cacophony. It was as if the professionalism and emotive facets of jazz and noise, respectively, met in the middle and had a child right there on the stage. The homunculus of sound that was right then and there continued to grow and transform into the specter of songs as Jandek asserted himself at his organ and the band clairvoyantly knew to chill just a little, just enough, so his man-lost-in-a-catacomb vocals could climb out and be revealed. As all of this music was improvised, the audience could only catch those words that were audible. Jandek was singing from a book on his organ, and the sound he pulled from those keys was akin to the Tall Man from Phantasm crooning along with a cathedral organ. It was the church of Jandek, and everyone quieted down for the sermons.

Over the course of eight songs, the band went from cathartic noise to slow-moving sound hodgepodge, swelling and throbbing underneath Jandek’s eerie organ tones, and culminated with a song as close to pop as an improv band could get. During the midpoint of the set, Yeh kneeled with one of his cylinders and blew it like a didgeridoo, passing his hand over the end to focus the wind against the microphone. Jewell pulled out one of his toys, a tin funnel with an embalming tube attached to the spout (like a beer bong) and gurgled through it, his free hand scritching and scratching a guitar pick against the grain of his drum head. Dicenzo kept the sound on this planet, warping his bass chords through the Echo-Plex sparingly. Jandek diligently kept on those deep organ keys, until the swell of sound approached full intensity and he changed keys, pushing the noise back so he could interject vocals. This formula, while incredibly effective for the first five songs or so, began to wear at the hour mark. As the crowd was informed before the set that it would last only an hour and a half, everyone realized that this would be the only time they would be able to experience a performance of this ilk and kept patient. Incredibly, Dicenzo, Jewell and Yeh, all bearing gifts from their respective ends of the musical spectrum, were able to speak Jandek’s language fluently and with purpose, and not one person in the crowd doubted their conviction to the translation. Sometimes things just have a way of working out.

Radio Silence/A Selected Visual History of American Hardcore Music

Columbus Discount Records vs. Sub Pop

Skins & Punks

Kraftwerk and the Electronic Revolution

Agent Orange Live Review

Alice Cooper Live Review

The Shoegaze Top 10

Digital Downloads Round-Up

Live Reviews of Radiohead and Bon Iver

Joe Strummer: The Future Is Unwritten

An Agit Writer at the Pitchfork Festival

Daft Punk's Electroma

R.I.P. Noel Sayre

Heavy Metal in Baghdad