The Future Is Unwritten

by Stephen Slaybaugh

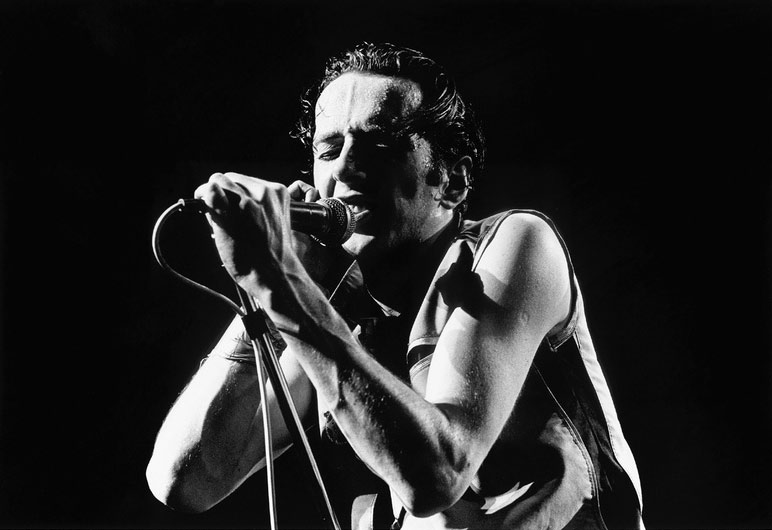

There’s been countless cinematic retellings of punk’s heyday, with a good portion of them focusing on Britain’s storied iconoclasts, the Sex Pistols and the Clash. (The rest usually zero in on the Ramones.) Having already directed a film on the former (The Filth and the Fury), Julian Temple turned his attention in the direction of the latter, focusing on Joe Strummer, the band’s rhythm guitarist and primary mouthpiece. But just like The Filth and the Fury wasn’t a simplistic, straightforward telling of the Pistols’ story, neither is Joe Strummer: The Future Is Unwritten (recently released on DVD) just a standard biopic.

Temple’s primary structure for the film is a forum with which Strummer himself was enamored: the campfire. With Joe’s World Radio broadcasts interjected as soundtrack, Strummer’s bandmates, friends, fans and associates gather to remember the departed singer. (Strummer died in 2002 at the age of 50 of congenital heart disease.) It’s the perfect vehicle as Temple is able to cover all aspects of the man’s life depending on who is telling the story. Childhood chum Dick Evans and cousins Ian and Alasdair Gillies reminisce about Joe as a boy (then John Mellor) through a montage of photos from the diplomat’s son’s childhood years. Former 101’ers recall their experiences with their former bandmate between seldom seen archive footage.

Of course, Strummer was best known for his work with “the only band that ever mattered,” the Clash. Drummer Topper Headon’s recollections of Joe as being somewhat intimidating and of his eventual ousting from the band as a result of heroin addiction are particularly candid. Similarly, guitarist Mick Jones seems to let his guard down a bit, revealing his misgivings that the Clash never reunited. Such memories are matched to rare video of the band in their prime. However, conspicuously absent from The Future Is Unwritten—and this is one of the film’s few faults— is bassist Paul Simonon. I mean, if Terry Chimes (the band’s first drummer who later returned to fill in for Headon) and Keith Levene (the band’s third guitarist in their short-lived initial five-man line-up) are going to be included, Simonon had better be as well.

Perhaps most interesting is the material covering Strummer’s life post-Clash. Even the 10 minutes spent on the usually ignored period when Strummer and Simonon continued on without Jones is more than the Cut the Crap-era Clash is ever paid. Friends tell of Strummer struggling to regain his confidence after the band was finally put to bed, and how he eventually found his voice again by melding all the music that had held his interest over the years. It seemed with his new band, the Mescaleros, that his career had been reborn after a decade of being almost completely dormant. Hence, his death was all the more tragic.

With each one of the many people Strummer touched during his life—from Matt Dillon and Jim Jarmusch to Bono and Joe Ely—recalling their time spent with the man amidst the glow of a campfire, the film is imbued with much more than the just the cold hard facts. The fire reflects the warmth with which most remember Strummer, as well as lending a communal feel that would sit well with the former squater and punk progenitor.