Balloon Man

by Stephen Slaybaugh

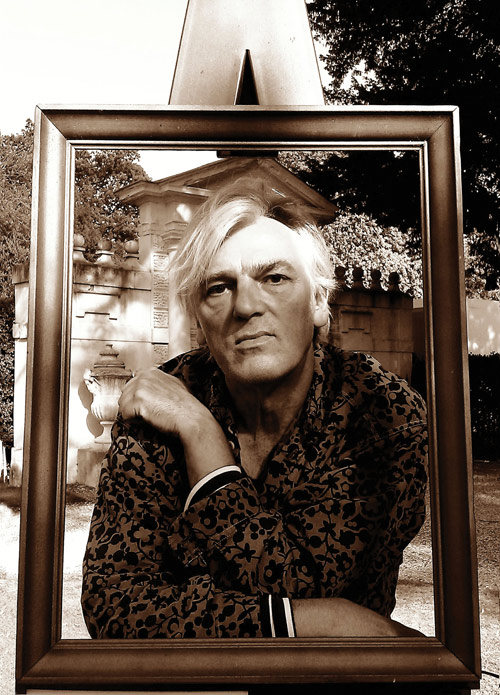

Since emerging as the leader of the Soft Boys in the late ’70s, Robyn Hitchcock has proven himself to be a songwriter unlike any other. Though the Soft Boys, who disbanded in 1980 after two albums, are often remember for “I Wanna Destroy You,” an anti-war ode often mistaken for punk nihilism, it is the idiosyncratic songbook that Hitchcock has continued to expand in the subsequent years that is more remarkable. In exploring love, death, and the strange entaglements of everyday life, Hitchcock has created his own lyrical lexicon of surreal imagery and quirky wordplay. His songs occupy their own realm, one which gurgles with fleshy tendrils, fishy creatures, and frog men having tea amongst the moss.

Since disbanding his backing band, the Egyptians, which included Soft Boys Morris Windsor and Andy Metcalfe, in 1993, Hitchcock has worked with varied ensembles, including the Venus 3 (Peter Buck, Scott McCaughey and Bill Rieflin) for three records. His latest album, Love from London, was made with Paul Noble, a producer and bassist more likely to be found working with pop groups like Sugababes. The pairing isn’s as unnatural as it might seem, with Noble’s electronic touches meshing with Hitchcock’s quirkiness particularly well on cuts like “Death and Love” and “I Love You.” In many ways, the new approach helps differentiate the album from past records dominated by acoustic guitar.

Hitchcock recently turned 60 and, to celebrate, played a concert in London where he performed songs from each of his records. With his past and present so succinctly juxtaposed, it seemed the perfect time to catch up with him on the phone.

Your name often has the word “cult” proceeding it, as in “cult following” or “cult singer-songwriter.” Do you feel “culitish” or that you engender a certain breed of fan?

Robyn Hitchcock: I think I define “cult” by now, don’t I? It used to be Manson and now it’s me. It’s fine, it’s just a way of saying that some people get what I do and most people don’t for some reason. It could have something to do with blood groups. Occasionally, there are windows through which more people see me and then those windows close again and I’m only visible to a certain coterie of people. I don’t really know. I’m too wrapped up in myself to know how or why I appeal to other people, apart from obvious intersection points, like if you like certain kinds of music—late ’60s music particularly—then you’d like me, I suppose. But even that’s not guaranteed. As long as enough people are listening to keep me going—which there are—then I’m okay.

You’ve worked with people like Peter Buck, Johnny Marr, and John Paul Jones, who have enjoyed massive success...

RH: I have, but they’ve all been with figures who have appealed to the popular imagination in a very broad sense. I don’t know how they themselves would have fared on their own.

But being around those people, have you gotten a sense of that sort of superstardom and does it bother you at all that that kind of success has alluded you?

RH: Do you mean am I peering jealously into their backsides, waiting for them to take me out to lunch? No. It’s very much a scale. Usually, wherever you are, there is somebody who is better off than you are and someone who is worse off than you are. From my perspective, there are musicians I know who are more respected and wealthier than me and those less so. The thing is to make the most of what you have. It is in our nature never to be satisfied, but on the whole, I don’t know that being rich and famous necessarily satisfies anybody. It tends to set up certain hungers that are hard to appease. You develop a monster you have to feed, and you can’t tell it that it’s had enough. I do know people who have coped with it extremely well, but they are usually people who are musicians rather than celebrities.

When I went into this, I was more of a personality than a musician, and to some extent, I still get reviewed for my attitude more than for what I actually do. But that’s the nature of the business. What I am now at 60 is a pretty well respected guitarist. Acoustically, I am a pretty good guitarist, and I’m erratic on the electric guitar. I have the respect of my peers, and I’m able to work with people like Martin Carthy, Graham Coxon, and Peter (Buck), obviously, for a long time and a little bit with Johnny Marr, as you say. I feel like I’m in good company as a musician. And JPJ (John Paul Jones), who has a broad palette and many musical accomplices. I saw him two weeks ago playing with a Norwegian improvised group called Supersilent, which has no vocals and no arranged songs. The music just exists for an hour and a half and then goes away again. He goes from that to working with Dave Grohl and then to the opera he is working on. John really enjoys being unconfined, and that’s quite inspiring. Most of us like to play with other musicians is what I’ve discovered. Musicians are curious, a little bit envious, and sort of fascinated by each other. I’m much more interested in and know more about musicianship than stardom, but the other danger with stardom is that you become famous for being on the map rather than for why you are on the map. I have no interest in that at all.

I read an interview where you were talking about how you see yourself now as more of a performer than simply a songwriter...

RH: As much as, yeah. I originally wanted to be a songwriter. I didn’t really think I was a very good singer or guitarist, but I was good enough to perform my own songs. I still think that I’m finding my own voice. I’m learning to relax and to sing more gently, rather than hollering or sing in a shouting way. I’m still working on performance. Just standing there with a guitar, there are so many different ways you can project and use different nuances of your voice. I’m still learning it just as I’m working on variations of the G chord. I haven’t gotten bored playing the acoustic guitar at all and I’ve been playing it for 43 years!

Taking that view of being a performer, has that changed the way you approach making records?

RH: Not really. The records tend to be reactions of the previous ones. If I make a sparse record, I’ll make a lush record next, and then I’ll make a sparse one again. I don’t think I’ve learned anything about making records. I know a certain amount about writing songs. A record, especially a single, has a life of its own. An LP is a mood, and a single is like a very short story. But a single needs to have enough monosodium glutamate or high-fructose corn syrup—well, maybe not as toxic as that—but some sort of sugar buzz to make you want to play it again. The album was an arbitrary length determined by how much music you could record on a vinyl disc and that changed with the CD and it became too unwieldy. But there is still a reflex action a lot of us have to make albums because that’s what we were taught to do ever since Sgt. Pepper. I think it’s still possible to do a collection of songs that have a mood or an atmosphere that will make you want to listen to it, the way you want to listen to Astral Weeks or Time (The Revelator) or I Often Dream of Trains. It tends to be the moody records that are the ones people want, the dark green ones that plumb the depths. I can’t intentionally make those records, but I’ve made a couple records that do have a mood people seem to like. The other ones are more like collections of songs, and I have no idea if I’ve recorded them well or arranged them properly or performed them right—I just don’t know. There are probably things I just don’t get about making records, unfortunately. Maybe if I could get hold of Brian Eno...

It’s interesting the way you are talking about records because I was thinking that with this one maybe you tried to suit each song to a particular style.

RH: I don’t know. I don’t think anymore than usual. We tried to bring out what we thought the right feeling was in each song, but I don’t think they differ that much. But I don’t have that much perspective on it. I’m very happy with it as a collection and as a sound. Paul did a really good job in mixing it, fine-tuning it, and putting in all these blips and warbles and things that I wouldn’t know anything about.

I didn’t mean that it’s incohesive in a negative way, but that the songs stand on their own apart from each other.

RH: Hopefully they’re not all different versions of the same thing. They’re not 10 asparagus stalks or 10 fish sticks. There’s a tomato and a grapefruit and a carrot and an avocado in there.

Having written some 500 songs at this point in your career, is it difficult to keep from repeating yourself?

RH: No, but there are probably patterns that I go to. Like a painter might be partial to blue or green, there are probably certain musical flavors that I like that I go back to a lot. Then there are other things that I discover that I incorporate for awhile. Like when people get hold of something like a new watch or a new boyfriend or a new girlfriend, they play with it a lot and then it becomes part of their life.

Lyrically, you use a lot of the same kind of imagery that tends to be sci-fi inspired. Did you grow up on sci-fi novels that came to bear on your songwriting?

RH: Yeah, HG Wells, JG Ballard, Ray Bradbury, Brian Aldiss, and the dystopia novels like Brave New World and 1984. “The future’s uncertain and the end is always near,” to quote Jim Morrison, but fraught with possibilities. The end is always near for us because it’s in our nature: we aren’t designed to last. That’s why I see apocalypses everywhere because I know we’re not going to last very long. Our individual lives are short so we have to live with the knowledge of our finite consciousness, and in that period, we desperately produce things. If I knew I was going to live for a thousand years, I’d probably write only one song every decade. We’d all work a lot slower because there’d be no rush.

But yes, I was very aware of what you call science fiction. And my father (Raymond Hitchcock) wrote a number of novels which were un-categorizable. They were somewhere between comedy, satire, science fiction, and sex romps. He had an imagination and a sense of humor so they had a lot of trouble defining him. I’m pretty much the same, only I work in the field of music. If I have a guiding principle, it’s that you can put anything in a song lyrically. Musically, my guiding principle is that I’d never do anything that The Beatles wouldn’t do. That marks me as a conservative and a traditionalist, even though during their day The Beatles were very inventive. But I think it gives me a good grounding as a songwriter because there is something about the instinctive way The Beatles constructed their songs that have made them last. I hope my songs will last because they are well made. I know that my template is an old one, but I think it’s a good one. But my lyrical approach is pretty much my own.

You just did a 60th birthday party show where you played material from every record, right?

RH: Yeah, we went backwards. We started with Love from London and then went back through every record that I’ve released, finishing with A Can of Bees, the first Soft Boys album. It was fun!

Did you have the people who played on those records perfrom with you?

RH: Yeah, I had Morris Windsor and Kimberly Rew from the Soft Boys. I had Nick Love and Mark Allen, who were both in one of my songs, “Clean Steve,” come and sing on it. Green Gartside from Scritti Politti, who is a more recent friend, played, and I had my recent London band—Paul, Jenny Adejayan, Lucy Parnell and Jen Macro—and Graham Coxon, Steve Irwin, Terry Edwards and Tim Keegan. So yeah, I had a gallery of old and recent friends helping out.

In going over every record you’ve made, are there ones that you found you like less than when you originally made them or albums that you like more than when they originally came out?

RH: There are songs that I’ve outgrown here and there, but a lot of my old songs seem to have known more about life than I did. It was as if one part of me was warning the other part, “Hey, look! This is what you are doing! This is what you are missing!” It was like the songs were a kind of periscope that could look above my immediate feelings and see my overall situation. Some of them knew more than I did, and other ones sound a bit childish and I don’t do them anymore. But it wasn’t hard to find at least one song off each record that I liked, and I did some of the more popular songs and some of the more arcane. It was great, though, we just went backwards and accelerated into the past.

There are a couple places on the new record where it seems like you are dealing with getting older. Do you find that as you get older you are more conscious of it?

RH: No, I was actually more elegiac and did more looking back mournfully 30 years ago when I did I Dream of Trains. Most of my wistful songs were written when I was turning 30. I’m always aware of mortality. Along with fish and cups of tea and dodgy English sex, I’m associated with being a nostalgic, mournful, retrospective guy. I’ve always looked backwards. I’m not aware of having any particularly new perspective on life in these songs.

My theory is that life flows through us rather than we go through life. People think you go through life and see different things, but I think life goes through us and perhaps we’re not moving at all. Life goes through us, and at the end, it is drained out of us, and what was us is just a husk. A newly dead person is so like a living person, but there is one vital thing missing: life. Maybe we don’t die at all, just our bodies die. We are our bodies while we are alive so it’s a bit of a paradox. But the current of life is passing through us. You need love because there is death, and certainly you need sex because there is death. We want to hang on to each other, but you can’t hang on to anyone or anything, and even yourself goes in the end. That’s where romance and sadness come from, because you want to hold onto someone and you can’t.

You were talking before about the apocalypse. “The End of Time,” which ends the record, obviously seems apocalyptic. Is that about your own apocalypse or a broader apocalypse?

RH: Yeah, because we are all finite, it makes us think in terms of apocalypses. “Après moi le déluge.” After me, the flood. Life cannot possibly go on without me. Who will see the world when my eyes are closed? There will be no one there to see it (except everybody else). But by the same token, whether we all die at once or if we die in sequence and are born in sequence, as has happened, it doesn’t make that much difference. It’s just each of us dying, though it’s a more scary thought for it to be in one go. Existence will carry on regardless of the human race. We didn’t invent existence, we just invented the word for it. Obviously, I think about these things and I always have. I don’t think I am anymore apocalyptic or obsessed with mortality at 60 than I was at 20. I suppose the only thing I’m more aware of is the need to just get on and do things while I can, so I feel less like sitting around, putting my feet up and gazing back over the years. I feel more like getting out there and doing it while I can.

Is there some reason you would stop doing this besides physical limitations?

RH: No, absolutely none. Even if I couldn’t tour or was under house arrest or the Vatican put out a fatwa saying that I would be slain if I released anymore records, I would go on producing music even if no one heard it. And if I couldn’t make up songs, I’d paint or draw. I’d like to carry on producing stuff even after I’m gone if I can find a way to do it, like endow a computer with some of my neural circuits and say, “Off you go, son.” I’d happily send my brain into eternity to continue producing things.