The Kids Are Alright

by Stephen Slaybaugh

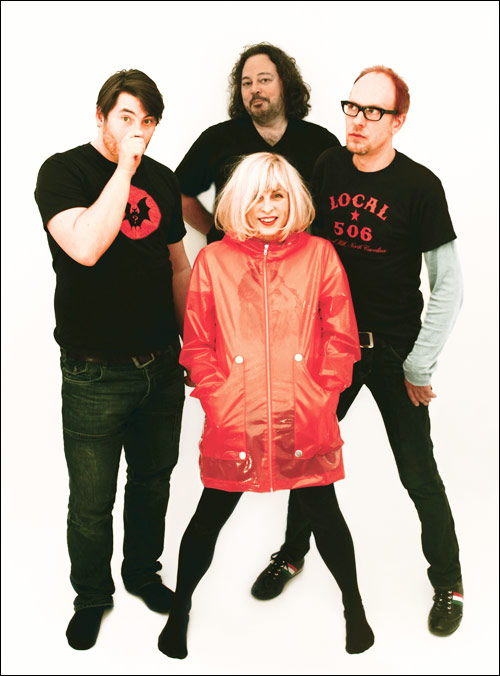

Dutch band Bettie Serveert first came to the attention of American audiences as part of the indie rock vanguard on the Matador label in the early ’90s. Their debut, Palomine, was marked by vaguely bittersweet pop songs highlighted by Peter Visser’s frayed guitar jangle and Carol van Dijk’s brusk vocals. Though they never strayed too far from that combination, after a couple more albums, American interest in the band waned. But though records have become more sporadic and drummers have come and gone, Bettie Serveert has continued to persevere, much to the joy of their devout audience here and abroad.

The band’s latest album, Oh, Mayhem!, finds them taking a straightforward approach, carving out 10 rough-edged pop songs that don’t lack for hooks. I caught up with Visser to find out how things have changed and stayed the same over the years.

It’s been a few years since the last Bettie Serveert album. Does that feel like a long time to you or the natural time between releases?

Peter Visser: We released the Me & Stupid album in 2011, so that means more or less an album out every year and a half or two years, which is kind of long still.

Has the creative process changed over the years or is it the same as when you made Palomine?

PV: That’s a difficult question. It’s changed a bit, but not a whole lot, even though Palomine was made in a different setting with a different drummer. These days, Carol starts a song and after she has some bits and pieces, she and I get together to work on it and demo it, then go to the practice space with the whole band. Then again, for this album, two songs were written with the whole band in the practice space, so it depends on the situation and the vibe.

You recorded Log 22 yourself, but you’ve gone back to studios since then. Did you discover you didn’t like recording yourself?

PV: Log 22 was really great, because it was the first time we did everything in-house. I had bought a 16-track recording machine, and it was like being in kindergarten. You could do anything you wanted to do, whether you were going to use it or not. We found out with a couple CDs after that, though, that when you record everything all at home, since you can do everything in ProTools, you polish it way too much. I found myself working on an outro for several days. So then we thought, if we book a studio for just a couple days and play live, we’d get back some of the rawness. Many times, people have said to us that they like the CDs, but that we flourish live. So we thought we’d play live in the studio and have the best of both worlds.

I read that you only had half the songs written when you went into the studio. Did you make the others up on the fly?

PV: Not really. Half the songs were more or less finished, and the other half were just skeletons of songs. It was kind of tricky because we only had five days. You never know what is going to happen, so we were lucky to pull it off.

Private Suit was a pretty mellow record and the ones after—especially the last two—have been more bombastic. So that’s been pretty intentional then?

PV: Private Suit was made with John Parish, and he had a vision and a sound in mind. With this one, we had Joppe as drummer, and he plays really loud so sophistication is out the window. Also, for some reason, the older we get, the more fun it is to play louder. This one is also back to basics, which is nice because the way you play a song on the album is also the way you play onstage.

You were talking about booking the studio for a set amount of time, and I was wondering about the economics. Is it the same in Holland these days as it is in the States, where you don’t sell records and everything has to be scaled back? Is there still government money available for bands?

PV: The government is cutting back on subsidized venues and such. Last year, they cut back like 100 or 200 million Euros on culture, which is a lot of money for such a small country. A lot of orchestras and venues had to close. Then, it is the same as in the United States, where all the Virgin Records and shops like that are closing down. There are almost no shops where you can buy records. So for a band like us, who isn’t a Top 40 band with massive hit singles, it’s kind of hard. We try to get by and maintain the band. If I look back when we just started, the advances we had in the early ’90s, that’s no longer happening.

The song that ends the record, “DIY,” seems almost like a mission statement. Does it take a certain amount of self-motivation to keep the band going?

PV: The motivation is there, and all you need is the money to make it happen. The love of music and love of playing live is still there. If it wasn’t, it would be impossible to make a cool record. You have to love your music because otherwise it will be fake.

Over here, you guys are still largely remembered for Palomine. Do you feel that way and is it frustrating to you that you are still living up to that record to some extent?

PV: Yeah, it’s a blessing in a way and it’s difficult sometimes. When we last toured the United States, the people in the audience were appreciative of the new songs, but they always screamed for the old songs.

Tell me about the artwork. It looked like you were smothered with stuff.

PV: Carol told me that she had a dream with that cover for the album. We were making a video for “Had2Byou,” and Carol came up with the stop-motion idea. Every Thursday, we came together in Carol’s apartment, and one of the band members had to lie still on the floor and hold the remote control for the video camera, which made separate shots if you pressed the record button. In between shots, something changed on your face. We had like a million photos, which put together made the video. One of the photos became the album cover. For me, they had pancake batter and put it on my face and glued all the little things with the batter. I had to lie still for more than four hours. Afterward, I went to take a shower to get it off and the shower flooded. It was a fucking nightmare!

With the title, why “Oh, Mayhem!” and not just “Mayhem” like the song title?

PV: The “oh” gives it a little more lightheartedness, like a sigh. We translated it in Dutch, like “oh, crazy madness.” Mayhem can be good and bad. It can be destructive, but it can be constructive as well. Sometimes you have to break stuff to build it again. When you are in love, there’s mayhem, but it can lead to something good. So it was meant to show that it can go either way.

Would you say there was a certain amount of mayhem that went into making this album?

PV: There always is! There’s always a lot of craziness, panic, different opinions, and fights about different opinions. But you need to have that struggle to come up with something better. If you are satisfied easily, you take it all for granted. We want to have something special, and since we are easily bored with ourselves and what we do, we try to come up with something that pleases ourselves. Even the differences in musical tastes between us are really big, so to get to a point where all four of us are satisfied takes a lot of arguments. When it works out, it works out for the best.

You mentioned the Me & Stupid project before. Is that something that will continue or will it just be a one-time thing?

PV: You never know, of course, but the way it came together was there were two guys in Holland who had a project called In a Cabin With. They were looking for artists and musicians in Holland, and they’d take them to someplace in the world and make a record with musicians in that location. They approached Carol and asked her if she wanted to do it. They said she could go to Mexico, Australia or someplace else I can’t remember. Australia has always been on the list for Bettie Serveert, but it has never happened. Carol said—and I’ll always be thankful for this—she would go to Australia, but I had to go with her because we operate as a team. The In a Cabin With guys were subsidized by the government and they said that they would never get the money. Carol told them if that was the case, then it wasn’t going to happen. Someway or another, they got it together, and the two of us went over there. We recorded the album in Sydney and Byron Bay in a couple of days and the rest of the two and a half weeks we were on the beach.

Had you ever met the guys you played with before?

PV: No, but we used to have an Australian tour manager when we toured with Buffalo Tom. His name was Anthony Treuer. He used to live in the United States, but now he lives in Sydney. So I gave him a call and asked him if he knew of a fabulous bass player and drummer. He came up with a couple names, and it was the drummer of You Am I (Russell Hopkinson) and a bass player who used to play with Evan Dando (Matt Wicks). We went in the studio with them for two days, from noon to 6 o’clock. After the second day, we almost had the whole album done, and it felt like we had been playing together for 20 years. Then we went to Byron Bay and there were two singer-songwriters who could play whatever instrument you pointed at. We wrote a song together, and Carol and I wrote another song at the swimming pool where we stayed. It was a really relaxed way to make a record.

You guys tend to go someplace when you make records, even if it’s not as exotic as Australia. Do you feel like you need to hole up someplace to make an album?

PV: Yeah, we definitely need to be in quarantine. This time we picked a place that is in one of the highest points in Belgium, almost to the border of Luxembourg. It was really in the middle of nowhere. Herman (bassist Herman Bunskoeke) has a family and a job, and if we recorded in Amsterdam, he’d have to go home and take care of the kids. With the four of us being in that studio, there was a real focus. It was nice because there was a house with it, so we’d be in the studio during the day and at night in the house drinking wine, so it was kind of like being on holiday too.