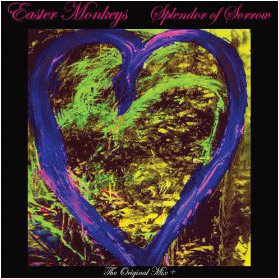

Splendor of Sorrow

Smog Veil

The Easter Monkeys formed in Cleveland in late 1980, featuring remains from local cult legends Pere Ubu, the Mirrors, the Impalers and the Kneecappers. It’s easy to forget how briskly that original punk-rock match-flick radiated, as even by 1980, rent-dodging slobs like these Easter Monkeys were invoking the names of Albert Ayler and Jimi Hendrix to stave off stagnation. And there is a bit of an expansive squall in the Monkeys’ mix, though it never envelops the more invigorating dung-flinging of the riffs and singer Chris Yarmock’s amazing city bus exhaust pipe of a wail. After all, the band’s true inspiration was Ghoulardi, the insane late night horror movie host who made every Cleveland kid in the ’60s a little weirder for the wear.

This remixed reissue of the band’s only album, posthumously released in 1990 (originally recorded in 1983 for a supposed cassette giveaway), starts with perhaps the most effective one-two kidney punch of any 1980s Cleveland rock album. “Take Another Pill” is a self-pharma excoriater that marauds around wearing an apocalyptic post-core frightwig in the vein of northeast Ohio scared slob-punk crews of the era (Spike in Vain, Shadow of Fear, Idiot Humans). In comparison, “Underpants” (“You might trip on them when they’re on your feet...”) then jarringly dishes out one of the catchiest, most fully realized “alternative rock” non-hits ever. And on it goes, back and forth, with slithering chorus-pedal guitar lurches turning a corner onto a knife fight and back down another damp, industrial wasteland alley.

“Nailed to the Cross” is like if Killing Joke were either murderous or funny, and spent their after-overtime hours drinking in the Flats in 1981. Suddenly, in the urban midnight haunt of this album, comes some skronky sax, a slide guitar racer (”Monkey See, Monkey Do”), then a spy-flick riff waltz with movie soundbites and requisite Ghoulardi reference (“Camera Fo’”).

The Monkeys’ swing was in line with some of the leathery graveyard punk that simmered through the 1982–85 vortex—Flesheaters, Gun Club, Poison 13, Tex & the Horseheads. But the cracked country roots of those acts aren’t as apparent here. Cleveland’s graveyards were right next to the dilapidated factories and shuttered record label offices of what was once the fifth largest radio market in the country. So the spooks herein are of the classic ’60s garage variety (“Heaven 357,” “My Baby Digs Graves”). Teen drummer, Linda Hudson, was the sister of Pagans’ singer Mike Hudson, so the sauced sourness of that crew comes through here too, if all a part of Cleveland’s amazingly fruitful, continually revelatory post-punk landscape.

Though mostly a spirit to the opaque, encroaching nuclear war mood of early-80s American midwest post-punk, there is a Blatz-hobble and humor hue (to the lyrics especially) that makes this album feel like a lost demo reel for a killer late-night movie show host job. Speaking of which, dig the fairly astounding DVD live show added to this packed package—two-camera, in color, from 1982, at the old Cleveland Agora (no longer standing). While the live extra-tracks on the CD are from 1983/84 (and show the band trudging towards even murkier material), this 1982 show has them at their peak, Yarmock holding court like if Gene Rayburn and Ghoulardi had a baby and they called it punk’n’droll.

Here’s where reissue reviews recall ubiquitous escalating drug problems and band fisticuffs. But really, who knows, as the fine first-hand liner notes are a reprint from an old CLE zine article and only recount the basic formation and Cleveness of it all. But in our era of every wart and zit in close-up, it’s probably best to leave the mystery of the Easter Monkeys mysterious.

Smog Veil seems to be on a mission to reissue every batch of boozers to strap on a guitar in northeast Ohio from 1979 to 1989, and this is their most essential release yet. So if I’ve got their ear, how about a complete Squelch comp? Huh, huh?

Eric Davidson

Make the World Go Away

Hozac

Wizzard Sleeve states right off on their Hozac debut, Make the World Go Away, that, in fact, “Alabama’s Doomed.” As citizens of the surly South, frying up the Lord’s Prayer into a glue-wave tainted themesong on the state of their ailing environment seems the perfect summation of what makes Wizzard Sleeve unique. Broadcasting from the middle of nowhere, there’s a streak of local color throughout Make the World Go Away, and like, say, TV Ghost, who carpet bomb the desolation of Indiana for inspiration, they use the middle of nowhere to their advantage. Not to dwell on trailerpark stereotypes, but it’s safe to assume that within this cultural ground zero, these kids would be townie wasteoids were it not for the Chrome and Thomas Jefferson Slave Apartments records snuck across the border. Wizzard Sleeve remind me more of the family that used to live a few blocks closer to the train tracks than I did, who would build the gnarliest haunted house out of cardboard and sheet metal. They’d spend a week outside with cheap beer, hammering and stapling, then after Halloween, become the mysterious recluses of the neighborhood for the rest of the year.

Listening to the intense downer vibes on Make the World Go Away, you get the feeling Wizzard Sleeve exists as this family, locked away in the basement, huffing high on their own writhing misery. As relative rookies, they’ve learned the mistakes of a band like the Lost Sounds and smothered the frantic mess of wires down to oozing stoner blues. On this opposite course, the acidic syrup of their wayward synths can get a little gruesome. “Excavating Heaven” drags to a bottomless pit, void of any enchantment by its end. It’s almost a graceful, if ugly in spirit, gesture—they know, at nearly five minutes of abject gook, “No Mongo,” will make you uncomfortable. But for every draining dirge, there’s an “Invisible City” or “Pterodactyl Meltdown,” songs that prove Wizzard Sleeve’s youth isn’t useless. Even among the crustiest of damaged punk, a diamond or two shine through. Just make sure to take a shower after living through this one.

Kevin J. Elliott

The Shape of Energy

Afternoon

With winter approaching at a fairly horrifying rate, it’s nice to have any type of reprise. Not everyone can hop on a plane and chase the sun, so the more budget-minded person seeking to extend the Indian summer might want to slap We All Have Hooks for Hands’ The Shape of Energy on the ole hi-fi.

The six-man band from Sioux City hasn’t crafted an ode to fun in the sun or a concept record to that one faithful summer. But they cram so much energy (no pun intended) into this record that The Shape of Energy plays like the soundtrack to a beach blanket romp nonetheless. The wide-open production style, the gang vocals and the live quality of the songs makes the record seem like reclaimed 45s from a jukebox found somewhere along Route 66.

The most striking thing about the album, however, is that this density never seems cluttered. While the touring version of the band is a core six members, there an additional four to five members in the studio. Like an updated version of Phil Spector’s famed Wall of Sound, a distorted lead guitar intertwines with a cleaner and more delicate rhythm line and horns echo the background vocals. (The only downside is that the vocals get the same treatment, and as a result only snatches of the lyrics reveal themselves at a time.) “Lessons Burned” shifts from a slow burning intro into a dance rave-up and then a hard-hitting down-tempo outro in a very tidy three minutes without sounding awkward or disjointed. Then there’s the epic galloping swoop of “Be Love, Be Wild” that seems custom made to accompany images of happy couples running through brightly lit fields.

Until global warming takes its inevitable and welcome toll on the climate, We All Have Hooks for Hands will serve nicely as an audio UV lamp.

Dorian S. Ham

Chez Viking

Lovitt

Is it possible to have distractingly perfect drum tuning? Where you know the drummer is human and playing a plain ol’ skins and sticks drum kit, but the sound that comes from them is more in tune than the rest of the instruments and you can’t get past it? The Mercury Program, while not crippled by this flawlessly peculiarity of perfection, is definitely hindered by the fidelity. It’s like having the Pope at a card game: sure, he’s a smart guy and probably decent company, but he’s infallible. If a trick goes down he doesn’t like, he’ll just change the rules to suit his favor.

Chez Viking could benefit from a little production dirt under its fingernails, a few sound skeletons in its closet, and maybe an aural lie told here or there. “Arrived / Departed” could have been a Rush outtake that just didn’t have enough grit to fit on Signals. Drummer Dave Lebleu is beyond proficient, dynamic and chromatically faultless—his parts make or break the songs. It’s just that the sound of the record loses appeal quickly because everything is apparent and obvious within the production, robbing the listener of any mystery. Instrumental bands should be, by nature, mysterious. They have no voice to explain what the songs are about, and when the sounds of the instruments aren’t questioned, they are taken for granted and then... well, boring. If the sounds the instruments make aren’t exciting, then why would anyone want to listen to the songs the sounds make up? High-fidelity recording used to be a professional standard and low-fidelity records were looked down upon as pedestrian. But in the age of Pro-Tools and Garageband, it’s almost too easy to make a record sound like Mutt Lange recorded it. The kicker is that the tracks on Chez Viking are almost fresh and exciting, but suffer from the purity of their virginal production. Sometimes the most perfect are the most dull.

Michael P. O’Shaughnessy

MP3: “Arrived/Departed”

Islands

Labrador

The best break-up albums generate the kind of emotional catharsis that rarely takes place in real life. Conversely, bad break-up albums allow the newly single listener to laugh at how silly people can sound when they whine about their ex. But Islands, the new album by Swedish indie rockers the Mary Onettes, is a break-up album that doesn’t really fall into either category. Phillip Ekstrom’s lyrics are straightforward, slightly sentimental (though never risibly so), and truthfully a bit unmemorable. But by writing lyrics that, in a different context, might be viewed as mediocre, Ekstrom has given voice to the average split-up, in all of its banality. The narrator of these songs isn’t about to go off the deep-end, nor is he making a mountain out of a molehill. As a result, Islands doesn’t always make for thrilling or profound listening, but at least it provides a refreshingly genuine take on the most universal of genres.

Existing in stark contrast to the relatively unadorned lyrics are the lush compositions that lie beneath them. The jangly guitars that are pushed to the forefront of other ’80s college rock revivalists, like Pains of Being Pure at Heart, are here obscured by over-the-top orchestra hits and schmaltzy yet guiltily catchy string melodies (think the Cure by way of Jens Lekman). Opener “Puzzles” is not only the most well executed example of this sound, but also one of the only songs of the past few years to achieve the dizzyingly epic Arcade Fire quality that so many lesser bands have recently attempted. Other highlights include “The Disappearance of My Youth,” which is driven by a manic reverb-soaked piano line, and the infectious “God Knows I Had Plans.”

The band rarely changes gears throughout the record, and a great number of the melodies sound suspiciously familiar. But the novel combination of outsized concert hall production and ’80s echo-pop, along with the everyman quality of the lyrics, makes for a unique album.

David Holmes

MP3: “Puzzles”

ALBUM REVIEWS

Morrissey, Swords

World's Greatest Ghosts, No Magic

Jacuzzi Boys, No Seasons

Pants Yell! Received Pronunciation

Annie, Don't Stop

Tape Deck Mountain, Ghost

Bassnectar, Cozza Frenzy

DJ/Rupture and Matt Shadetek, Solar Life Raft

Weezer, Raditude

Ben Frost, By the Throat

White Denim, Fits

Brilliant Colors, Introducing

Thee Oh Sees, Dog Poison

Holopaw, Oh, Glory. Oh, Wilderness.