Secret Earth

Ba Da Bing

For what do we, the impassioned fanatics of New Zealand’s Dead C, owe for the trio’s recent remembrance, revival and current renaissance? The resurrection of Siltbreeze? The current boom of bands aesthetically in debt to the euphoric improvisational post-rock sludge that arrived in the late ‘80s? Or the simple fact that the Dead C have never really left, and what’s remained dormant has been their itch to get completely bent again? It’s likely all three reasons. With the re-issues of classics Eusa Kills and DR503 by Jagjaguwar Records and a rare (and brief) tour of select cities in the States, a scum rush to gobble up each and every slab of abstraction the group has produced is a mania that has gone beyond insular collectors and into a forum of popular culture quick to catch up and crown them for triumphs of a decade past.

Grand enough an event then is the release of Secret Earth, which finds the Dead C returning, or maybe just turning back to the humble guitar/feedback/percussive caterwauling that was in stark contrast to their bucolic surroundings. Nothing sounded like the Dead C in those heady Siltbreeze days, and Secret Earth is a reminder of the strangulated sonic ubiquity albums like Harsh ‘70s Reality and Tusk represented. It was thought that maybe the trio was hobbling on in middle age, as previous releases had shown them lost in ambling minimalism and electronic blip fuckery not all that damaged or even unique. Within the Secret Earth none of that exists; it is pure in it’s adherence to amplified noise, industrial shrapnel propelled into feedback squalls, and drum jams never quite finding a comfortable balance. As with each successive album in Dead C’s “rock” era, there’s a density that forms from their perpetual crash; what may begin as a “song” coagulates into a mass of hypnotic chug. “Plains” is a perfect example, as its last five minutes are mesmerizing as a singular riff is repeated like waves ad nausea while everything in the periphery is blurred out under a muddy crust. Dig and dig, that’s where the Dead C rewards, deep underneath when the root is revealed. Secret Earth is another stunner for the ages.

Kevin J. Elliott

Welcome to the Night Sky

Labwork

On Wintersleep’s third album the band pushes against the darkness, sometimes reveling in the destruction, but just as often succumbing to the desolation of the losing battle. This album would sound great in a club with a crowd singing along, but it hits more than hard enough in the dark, when most of the world has gone to slumber.

Welcome to the Night Sky kicks in with mid-tempo histrionics, atmospheric chords, a pulsing bass drum, and racing high hat patterns, but the noise gives way to Paul Murphy’s desperate voice, drifting out of the “lost, lonely night.” One short verse and the band continues hammering out its instrumental discontent. This is largely the pattern for the duration. The band lays out an anxious explosion of distortion before Murphy chimes in with his esoteric, literate, and (usually) evocative scrawlings. Then the band rages on. It’s a pattern that fellow Canadians in the Tragically Hip mined 15 years ago and was then bluntly canonized by the mainstream success of York, Pennsylvania’s favorite sons, Live. Songs like “Dead Letter,” though more evenly paced and thoroughly forlorn, bring to mind Australian hitmakers Powderfinger, especially their almost painfully bleeding-hearted album Odyssey Number Five, now nearly a decade old. Wintersleep get more cacophonous than any of their forebears, however, and avoid the pitfalls of over-earnestness by drawing back to a slightly more patient and detached posture on “Astronaut,” “Laser Beams,” and “Oblivion.”

Murphy (the presumed lyricist, though the album contains almost no liner notes) is a devout humanist and symbolist and so, despite his occasional unwillingness to commit to cogent sentences, he satisfies the rules of alternative rock by providing chanted mantras (“belly of a whale, belly of a whale”) and pained proclamations (“we’re alone in this wilderness”). When the band pairs his intensely troubled revelations to its radio-ready, mosh-worthy bombast, the album falls into place as a worthy successor to the best of its aforementioned peers.

Matt Slaybaugh

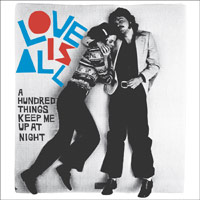

A Hundred Things Keep Me Up At Night

What’s Your Rupture?

The first two tracks on A Hundred Things Keep Me Up At Night prominently feature saxophone. It’s been awhile since I last listened to 2006’s Nine Times The Same Song, but I don’t remember any saxophone. I don’t generally like sax in rock music, but somehow Love Is All gets it right. Luckily, the sax is limited to only a few tracks.

Love Is All remind me of two other female fronted post-punk outfits, Essential Logic and Delta 5. The difference being that Love Is All also incorporate Swedish indie pop elements (see “Movie Romance” and album opener “New Beginnings”), as well as some Phil Spector production hallmarks like the reverb drenched wall-of-sound on “When Giants Fall” and “A More Uncertain Future.” The drum tracks often sound like the classic drums and tambourine beat from “Be My Baby,” while I can even hear the Selector in “Last Choice.” Love Is All are at their strongest when incorporating the post-punk, pop and noise influences equally. “Big Bangs, Black Holes, Meteorites” and the first single “Wishing Well” do exactly that and as such are definite standouts.

A Hundred Things Keep Me Up At Night is beyond catchy: it’s fun and you can dance to it. What else can you really ask from your Swedish indie rock?

Tom Butler

MP3: “Wishing Well”

Year of Explorers

KFM

I’m not one to suppose that in the present the entirety of Scotland’s music scene is without an original thought, but a great majority of the NME’s cheat sheet is rife with rip-offs and retreads—only stricken with that thick, tartan accent. Every couple of years, though, there are a handful of bands that pique the interest of the indie-rock underworld, and as we wait patiently for Franz Ferdinand to return (are we?), it’s pretty easy to revel in the wild experimentation and/or disco-punk herk-n-jerk of Edinburgh’s Magnificents.

In lesser hands Year of Explorers could be a disaster. In form and function, the backbone of the Magnificents’ songwriting relies heavily on the deft melody of Franz, but the band forgo the carbon copy by texturing their sound with a barrage of synths and circuit bending. To their credit, the Magnificents don’t succumb to simply grafting on electronic accoutrements to bolster their already catchy choruses, instead they operate in two modes, both of which make them unique to what could be considered a tired genre. “Ring Ring Oo Oo” is the most obvious, wholly romantic and new wave in its intent by showering the guitars with a glittering rain of Tubeway Army esotery. “How Longs Gone” is another example of this mainline pop, but gurgling and churning beneath are layers of echoed oscillations and keyboard snarl.

The most intriguing quality of Year of Explorers is its dark side, evident on the title track, where a menacing organ leads the future-punk into corners that recall Screamers and even late-period T.S.O.L.—if that can be believed. Still, as drugged and dreary as this apocalyptic, maximalist synth band becomes, a song like “Dedridge Cowboys” asserts that all the bright progressions and neon smokescreen are not for naught, but for adding a cheeky yet engaging gloss to their already infectious, if not everyman, pop.

Kevin J. Elliott

ALBUM REVIEWS

Skeletons, Money

Q-Tip, The Renaissance

Wild Beasts, Limbo, Panto

The Cure, 4:13 Dream

O'Death, Broken Hymns, Limbs, and Skin

Crystal Stilts, Alight of Night

Deerhunter, Microcastle

Like a Fox, Where's My Golden Arm?

Gang Gang Dance, Saint Dymphna

The Sea and Cake, Car Alarm

Tobacco, Fucked Up Friends

Magnetic Morning, A.M.

Her Space Holiday, XOXO, Panda and the New Kid Revival

Deerhoof, Offend Maggie