Parallax

4AD

As prolific as Bradford Cox is as a songwriter, his biggest fault has always been the inability to discern between what stands as an Atlas Sound recording and what should be reserved for a Deerhunter staple. That’s a good situation to be in, though, as I could have started this review by decrying Cox’s inability to edit his output. But among the multitude of releases under both guises—and the neverending freebies he finds fit for consumption—it’s hard to find a reason why he wouldn’t want to share everything. With Parallax, the excellent follow-up to last year’s glowing Logos, Cox does a fine job increasing that divide and further creating a world in which his solo endeavors and experiments can thrive. Where Deerhunter fires with more structure (and more of the trappings which one would associate with a “rock band”), Atlas Sound records tend to accentuate Cox’s true spirit as a hermetic bedroom-fidelity explorer, even as the sonic depth has grown with each album.

In the past, Atlas Sound recordings were where Cox focused on fine-tuning his fever-dreamed atmosphere. Sometimes this led to songs ambling in distant twinkles and blurred melodies played long past their enjoyment and falling into sleep mode. Or it meant dealing with a variety of whims that tore through cohesiveness. Logos, for instance, reveled in that drowsy idiosyncrasy and netted bright wondrous results, but didn’t feel whole. Parallax tends to reel in Cox’s penchant for drifting and in turn brings a new clarity to his most personal of songs. Before he might have hid amongst the micro-beats and syncopated synths of “Te Amo,” but here he has found a conspicuous voice that reaches for a higher register. Phrases are given abundant nuance, and it’s almost as if Cox is inviting us in for a change.

Various signs (new coif, high fashion glamour shots, tidier arrangements) point to Cox wanting Atlas Sound and Parallax to make his softer, introspective singer-songwriter persona more visible, and nowhere is that more apparent than on “Mona Lisa.” The simplest of Parallax’s tracks, it’s a folk-pop song made with acoustic guitars, sprinkled with piano, and on par with the best of Conor Oberst or Britt Daniel. The album’s centerpiece, “Mona Lisa” suggests this record is Cox’s first love letter. Whether written to his music or to his muse, the roomy bop of “My Angel Is Broken,” the lonely desolation of “Flagstaff” and the still elegance of “Terra Incognita” are directed towards an inspiration that hasn’t been there before. Perhaps it’s Cox’s want for his songs to be accepted on a plane outside of the Deerhunter sphere, on some kind of refined plateau. There are certainly moments, like the handful of songs following “Mona Lisa,” that project his songwriting as such. Still, Parallax is not a monumental shift. There are enough ambiguous qualities within the songs that keep Cox’s Atlas Sound strangely obscured. All one has to do is get lost in the murkiness of “Doldrums” to realize his obsessions with ambience, out-of-body psychedelia, and past 4AD artists who perfected what he is searching for here.

Kevin J. Elliott

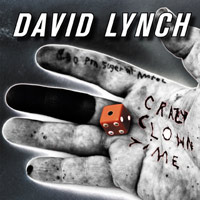

Crazy Clown Time

Sunday Best/[PIAS]

Iconic filmmaker David Lynch’s surrealist films have long employed music and sonic touches as part of their strange auras. Indeed, what would Blue Velvet have been without Roy Orbison’s “In Dreams?” Or Twin Peaks without Angelo Badalamenti’s score or Wild at Heart without the use of Powermad’s “Slaughterhouse?” It’s not surprising that the director has tried his hand at music-making, most notably on last year’s collaboration with Danger Mouse and the late Mark Linkous (a.k.a. Sparklehorse), Dark Night of the Soul, but Crazy Clown Time marks the first time Lynch has created a solo album.

As one might expect, Lynch’s latest endeavor is a strange bumpy ride. It begins with a collaboration with Karen O, “Pinky’s Dream,” that juxtaposes the Yeah Yeah Yeahs frontwoman’s soaring vocals with sepia-toned guitar reverberations. Nothing too outrageous. On the following track, however, Lynch takes an unexpected turn, running his own vocals through auto-tune and matching them to a techno beat and some repeating synth lines. Singing “I want to have a good day today” like it was a mantra of sorts, the track is mindless, but not soulless.

The remainder of the record is similarly bi-polar, Lynch playfully reveling in his own esotericism. “Football Game” is perhaps the most compelling of his strange forays. Narrating a tale of infidelity under the Friday night lights in a mealy mouthed voice, Lynch portrays a slice of small town Americana against a backdrop of minimalist guitar strokes and drum taps. “Speed Roadster” seems to have come from a similar place, one perhaps just up the road from Lumberton (Blue Velvet’s setting), and Lynch casts the same noir lighting on this song. Ultimately, Crazy Clown Time suffers for its eclecticism, but not without striking gold a few times.

Stephen Slaybaugh

Replica

Software/Mexican Summer

Remember the laser machine that turns Jeff Bridges into a computer image and zaps him into the Tron world? Or the killer Hal 9000–like building in the first season of X-Files or that printer Andy Warhol used to churn out a computer-generated portrait of Debbie Harry? Replica is the sound of those machines chopped down and screwed into one mega Voltron future-past tone bank. Oneohtrix Point Never is like the boy version of IUD, minus the sex fluid plus lots of cool analog synths and some piano sounds. I was tempted to write this review in binary, but I would never be able to capture the correct inflection. In fact, I’m not sure I have the right equipment to listen to Replica correctly, but if I dig long enough I might be able to find my mom’s old Apple IIGS and see if I can get the thing to boot up. In the meantime, I have to be careful not to blow my speakers. The title track is a haunting piano riff held up by atmospheric electronic swooshes and bimps which end up conjuring a slo-mo beach scene in my mind, waves crashing into gigantic eroded shore stones. Not all of Replica is sleepy minimalism, and while you may recognize some of the analog sounds, there’s no Boards of Canada easy dancer here either. “Sleep Dealer,” “Nassau” and “Child Soldier” are weird pastiche pieces, rhythmic, but not for the sake of base body movement. “Up” is a house party–ready head-nodder until around the two-minute mark, when the toms disappear into a swirling rainbow black hole of whale sex sounds and angels playing pattycake. If there’s a better song to accompany the thousand-yard stare than album closer “Explain,” I haven’t found it yet. Sure it’s interesting to see live electronic music, if only to see how they pull it off on the spot, but Replica is actually enjoyable to listen to, so let it work itself out on your big speakers.

Michael P. O’Shaughnessy

Dive

Ghostly International

Tycho is the alias of Scott Hansen who also makes his bones as a graphic designer under the name ISO50. It maybe a cheeky wink to the nerds or just a coincidence that he shares his musician name with a prominent mooncrater when his design work is often associated with the term “sun-drenched.”

Dive is an interesting beast. It’s an ethereal soundtrack to a travelogue, but isn’t just background music. It holds your attention, but doesn’t bludgeon the listener over the head. It’s a very smart record. Too many times all-instrumental sets skimp on musicality. The songs on Dive are filled with movement and ideas, but without being busy. It’s a fine balance of being evocative without being so abstract that it turns into mush, and Tycho hits the perfect blend. Even within the space there are tight song structures, yet it’s not as hooky as similarly structured songs due to the lack of obvious repetition. It’s sophisticated, but also has a loose organic feel to it. The combination of electronics with the occasional appearance of guitar gives it a warm and, well, sun-drenched sound. As the time falls back and the sun begins its journey to the land of forgotten things, it would probably be a smart move to throw on Dive and try to extend the feeling of endless summer for as long as possible.

Dorian S. Ham

Welcome to Condale

Apricot

You’d be hard pressed to find a band more suited to its name than Summer Camp. The London-based duo is a wunderkind collaboration between singer-songwriter Jeremy Warmsley and journalist Elizabeth Sankey. The twosome began releasing music under a cloud of anonymity via MySpace early last year, and then they exploded thanks to favorable, albeit unwarranted, reviews. Eventually, their identities were unmasked, and a little more than a year later, they’re releasing their first full-length, Welcome to Condale.

The album begins with a bang in the form of the dreamy synth-pop kicker, “Better Off Without You,” a blistering anthem of female empowerment. The magical aspect of the album is that it might as well be a soundtrack to your favorite ’80s movies, or maybe even the remnants of a movie in itself. In fact, the hazy eponymously titled song leads with a quip from a John Hughes film. Its predecessor, “I Want You,” is the quintessential ’80s homage, wrapped in heavy synths and loaded full of lust. It’s pure pastel pop and teenage nostalgia tied with a pink ribbon. “Done Forever,” with its creepy organ-like buzz, tricks you into thinking it’s a mere lament, but quickly coalescences into an electro beat, pacified by Sankey’s bluesy vocals.

Make no mistake, though, the upbeat mood changes sharply with the haunting, “Nobody Knows You,” a shrill plea with vocals as raw as Beki Bondage and the soul of Adele. For a self-proclaimed writer, Sankey has a beautiful, unrefined voice that shouldn’t be hidden by the written word. The vibe continues on “Down,” plastered with upbeat, fuzzy dreamscapes. At their best, Summer Camp is as enjoyable as Pains of Being Pure at Heart, while in their lesser moments certain songs ebb toward an affecting drone. Summer Camp has created their own soundscape of adolescent lust, love, loss and fun, which they summed up perfectly when they said that Welcome to Condale is their “love letter to the days of being a teenager.”

Jennifer Farmer

ALBUM REVIEWS

EYE, Center of the Sun

The Juan MacLean, Everybody Get Close

Skinny Puppy, hanDover

Low Roar, Low Roar

Tom Waits, Bad As Me

Gauntlet Hair, Gauntlet Hair

Strange Boys, Live Music

Spectrals, Bad Penny

The Beets, Let the Poison Out

Björk, Biophilia

Ryan Adams, Ashes & Fire

Real Estate, Days

Jane's Addiction, The Great Escape Artist

My Brightest Diamond, All Things Will Unwind