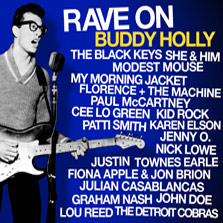

Rave On Buddy Holly

Fantasy/Concord

Though his career lasted just 18 short months, Buddy Holly and the music that he made are indelible components of the fabric of rock & roll. Before Holly died at the age of 22 in a tragic airplane accident that also took the lives of Ritchie Valens and JP “Big Bopper” Richardson, he and his Crickets made three albums and recorded more than 20 singles, though several of them were released posthumously. While hardly as flamboyant, Holly stands with Elvis, Little Richard, Jerry Lee Lewis and Chuck Berry as one of the architects of rock & roll. His distinctively hiccupy vocals and rhythmic guitar playing were direct influences on the second generation of rock & roll, specifically the Beatles, who chose their name because of its similarity to the Crickets, the Rolling Stones, whose Keith Richards attended one of the shows on the Crickets’ 1958 British tour, and Bob Dylan, who saw Holly play in Duluth just two nights before his death. Holly’s talent extended to experimenting in the studio (you can hear it in the guitar tones of “Peggy Sue”), and one can only imagine the records he would have eventually made had his life not been cut short.

The Lubbock, Texas native’s legacy, though, is sometimes not remembered with the same reverence as his contemporaries, perhaps due to the brevity of his career or as a result of his mild persona. Fortunately producer Randall Poster and Gelya Robb have chosen to commemorate Holly’s upcoming would-be 75th birthday with a 19-track collection of artists reinterpreting his work. Such records are never without some bumps, but the thought is to be applauded regardless.

That said, there are some true gems here. The Black Keys lead off the record with a sparse, but moving rendition of “Dearest,” which is then followed by a version of “Everyday” done by Fiona Apple (who knew she still sang, right?) and Jon Brion that’s faithful to the original, but shows how truly timeless the song is. Cee Lo Green’s “(You’re So Square) Baby, I Don’t Care” accomplishes the rare feat of retaining the feel of Holly’s version (mainly the jumpy backbeat) while adding all kinds of new instrumentation. Julian Casablancas, along with backing from Matt Sweeney, manages a similar accomplishment with the album’s title track, blending effects laden guitars and synths while emulating Holly’s vocal inflections.

Modest Mouse’s “That’ll Be the Day” and Lou Reed’s “Peggy Sue” only resemble the originals in their lyrical content and vocal melodies, but work nonetheless. Much less successful is Paul McCartney’s take on “It’s So Easy,” which is belabored and contrived (sorry, I don’t buy a 60-something Brit jive-talking), while She and Him’s “Oh Boy” falls utterly flat. And I probably don’t need to explain why Kid Rock shouldn’t even be on here. Otherwise, though, there are few duds, and it’s exciting to hear Holly’s music given new life with such great results.

Stephen Slaybaugh

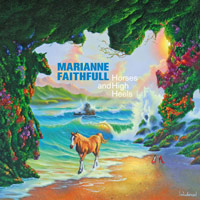

Horses and High Heels

Naive

Over the course of Marianne Faithfull’s long career, she’s tried out plenty of musical genres. She began as a folkie starlet singing mod-inspired songs written mostly by other people, but moved on to weed-scorched rock in the ’70s and then cocaine-laced disco in the ’80s. She eventually developed an obsession with Weimar-era workers’ music, a la Threepenny Opera and Kurt Weill, before teaming up with alt-rock icons like Beck, PJ Harvey and Nick Cave earlier this decade.

All of this has informed Horses and High Heels. There’s groovy boozing in “Back in Baby’s Arms,&rdquo highfalutin, properly annunciated vocals in the title track, and drug-dusted eeriness in “Love Song.” With clean and professional production and top-notch musicianship, there’s nothing missing from this album—except for the weirdness. Faithfull’s been involved in pretty much every musical scene that’s mattered over the last 40 years, but it’s the freaky stuff that’s been the most interesting on past records. Here, though, there’s no “Eye Communication” or “Blue Millionaire” or “Why D’Ya Do It?” Maybe this is Faithfull’s way of saying that those years were fueled by some pretty evil stuff, and it’s time to grow up and play it straight. There are running themes of regret, nostalgia, and times passed in the lyrical subject matter, with songs like “The Old House,” “Eternity,” “Past Present and Future” and “Goin’ Back” all dealing with what happened and where the singer is left after those changes. Faithfull’s life story is one of the most interesting in rock lore, especially considering that she’s related to one of the most powerful empires in human history and the guy who “masochism” was named after. She spent most of her time destroying herself in the periphery of rock royalty, and Horses and High Heels is a pretty clear reflection of the decisions she made when she was on top of the pop world. This record might not lift you out of a depression, but it might give you comfort knowing that someone else had it easier and fucked it up worse.

Michael P. O’Shaughnesy

MP3: “Why Did We Have to Part?”

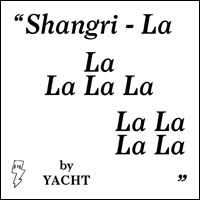

Shangri-La

DFA

Yacht, excuse me, YACHT (a.k.a. Young Americans Challenging Higher Tecnology, but without proper capitalization, it’s merely a boat) is a genre-bending, technologically stimulating multimedia project/band created in 2002 by Jona Bechtolt. Bechtolt released three albums and toured relentlessly before vocalist Claire L. Evans joined the effort on 2009’s acclaimed See Mystery Lights. Two years later, the duo shows off their musical progression on their latest release, Shangri-La.

From the first songs, the upbeat electro jam, “Utopia” and it’s unequivocal opposite, “Dystopia,” the weighty content and theme of the album becomes abundantly clear. Despite lovely vocal harmonizing and haphazard layering (Architecture in Helsinki meets the late 1980s), the content is melancholic and hopeless, delving into subjects ranging from destruction to overpopulation to religion. Maybe Shangri-La is meant to serve as a merely ironic warning of sorts? Some lyrics are blatantly attention-grabbing (“The earth is on fire. We don’t have no daughter. Let the motherfucker burn”), while others are eloquently structured in the form of thought-provoking statements (“We let our children multiply, because we’re afraid of dying.”) On the whole, however, Bechtolt and Evans have an uncanny ability to structure perfectly paced poetics out of the strangest tempos, rhythms and beats. And it’s hypnotic. Though YACHT is primarily an electro-pop outfit, it’s clear that Shangri-La draws upon various bits and baubles of inspiration, from the disco groove on “I Walked Alone,” to the blues- and funk-flecked “Holy Roller.”

Though the tracks on the album are loosely based on the concept of its title (the elusive place concealed from man), each song proffers some new insight into the destruction of society, mankind and the earth, but offers no solutions. One may never know the answers, but regardless of the implications of such heavy thoughts, what wondrously danceable ruminations Shangri-La doth make!

Jennifer Farmer

MP3: “Dystopia (The Earth Is on Fire)”

Eye Times

Trouble in Mind

It’s been three years since the release of the Wax Museums’ self-titled debut LP, but there’s little sign of rust on Eye Times, the band’s first release on the Trouble in Mind label. Hailing from the fertile Denton, Texas music scene, the quartet’s early 7-inch records quickly built the band a reputation for delivering blistering punk jams. Eye Times certainly builds upon that reputation, with the major evolution perhaps being the band’s more controlled and precise attack.

Indeed the 13 tracks on Eye Times, which clocks in at just less than 22 minutes, come off as short, repeated blasts delivered with a snotty Ramones-like efficiency and an attitude reminiscent of early Devo. Lyrically, the album playfully explores everything from the mundane in “Sunburn” (“I don’t want to wear sunblock. I think it looks so uncool,”) to the raunchy in “Breakfast For Dinner” (“I don’t want bacon. I just want what she’s got.”). But it’s not all pure hijinks: the album’s centerpiece, “Bruiser,” could be the punk anthem of the summer. The sound on Eye Times is essentially the standard guitar, bass, drums and vocals approach, with just the occasional incidental electronic noise (as in the synth effect that adds extra creepiness to “Mosquito Enormo”), but the band’s mastery of the punk idiom keeps the proceedings from getting stale.

Ron Wadlinger

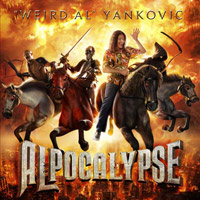

Alpocalypse

Jive

I’ve seen Weird Al Yankovic live a total of two times. The first was in the early 2000s, when I was about 10 years old and he played the Del Mar Fair in suburban San Diego. He was my favorite artist. The second time was when I was 19 years old at this year’s Fun Fun Fun Fest. Aside from a few new songs and an updated polka, the differences were pretty much indistinguishable.

Just like how Alpocalypse is pretty much indistinguishable from the rest of the records the man’s made during his career, which, surprisingly, is going on 30 years. But Al wins, where, say, Gallagher and Carrot Top fail, out of pure talent. He’s parodying good pop music, and maybe the hooks of “Born This Way” and “Party in the USA” work regardless of any jokey context. But his survivability and relative hipness is a testament to a long career of not taking yourself too seriously and keeping a clean nose. His jabs are easy—Queen becomes an anthem against annoying ringtones, and the Doors, a moody Craigslist tribute—but they work with their barefaced, family-friendly, but not in a bad way, charm. And hey, dude can sing, dude can write, and dude can be funny, even at 51. We’re lucky to have him.

Luke Winkie

ALBUM REVIEWS

Seun Anikulapo Kuti & Egypt 80, From Africa with Fury: Rise

John Paul Keith, The Man That Time Forgot

Cassettes Won't Listen, EVINSPACEY

Jeff the Brotherhood, We Are the Champions

Elysian Fields, Last Night on Earth

Thee Oh Sees, Castlemania

Antipop Consortium, Knives from Heaven

Oneida, Absolute II

Nigeria 70—Sweet Times

Ford & Lopatin, Channel Pressure

Arctic Monkeys, Suck It and See

The Ladybug Transistor, Clutching Stems

City and Colour, Little Hell

Seapony, Go With Me