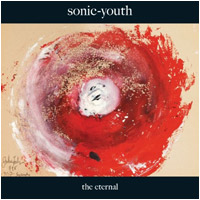

The Eternal

Matador

It’s been nearly three decades since Sonic Youth, having sprung from the intermingling of art and noise and punk strata in downtown Manhattan, started making records, and as such, each new release from the band is a paradox unto itself. With the band having long since cemented themselves into alt-rock’s foundations, a Sonic Youth record is no longer defined by how far it deviates from the norm, but rather where and how it deviates their norm. And there’s the crux of the conundrum: with each subsequent album further defining what a Sonic Youth album is (and isn’t), how can they sound like anything other than themselves when what they sound like is so distinctly nebulous? Can they exceed expectations when what is expected of them is to defy all expectations?

After the twin infinitives of Murray Street and Sonic Nurse with Jim O’Rourke, and re-orientations going even further back, Rather Ripped, Sonic Youth’s last release from 2006, was probably the most logical answer to that quandary. By descaling the band, both in personnel and in sound, Sonic Youth gave themselves room to renovate, maybe not so much on that album, but certainly on this subsequent record and first for Matador, The Eternal. With Mark Ibold (formerly of Pavement) becoming the full-time SY bassist after being brought on board to tour Rather Ripped, that could be taken literally. But more importantly the band has rediscovered their affinity for extrapolating within a (relatively) smaller framework, taking punk’s hard-boilerplate and rewiring with no-wave circuitry—much like they did on such albums as Sister, but with entirely different end results. Beginning coy and cool with “Sacred Trickster,” Kim Gordon’s paean to painter Yves Klein (if we’re to believe the press notes), they transition to “Anti-Orgasm,” easily the band’s post-millennial highpoint. At first comprised of noise outbursts and viscerally led choruses strung tautly together, the cut soon spirals into longer and looser bouts of the same that are no less exhilarating. It’s a juxtaposition of primal urges and refined deconstruction, which itself is an apt description for the greater portion of Sonic Youth’s output.

“What We Know,” one of a couple Lee Renaldo songs, works similarly, but in a much more composed manner. With the song’s guitar lines splintering at a moment’s notice, it’s the rhythm section that inadvertently takes the lead. Such is the case with “Calming the Snake” too; Ibold and drummer Steve Shelley lay down a B-line, Kraut-like groove over which guitar shards clash with and circumvent Gordon’s vocals, here emitting more sparks than have been heard from her in some time.

All is not golden on The Eternal (“Poison Arrow” is cliche by anyone’s standards), but in the grander scheme of the record, such minor foibles are hardly noticeable. Blowing minds may no longer be an option for these luminaries, but now simply satiating them is more than enough.

Stephen Slaybaugh

MP3: “Sacred Trickster”

Bitte Orca

Domino

First let’s get “Stillness is the Move” out of the way, because obviously it will stand alone as the one track on Dirty Projectors’ stunning new album, Bitte Orcathat will garner all of the praise and obfuscate the bewildering genius that lies in the heart of this record. In these three surreal minutes, David Longstreth’s sirens, Amber Coffman and Angel Deerodorian, weave an intricate tapestry of soulful harmony atop an attention-deficit beat and elegiac strings, in the process giving just as much credence to Mariah Carey as they do Homogenic-era Björk. Through sheer pop exuberance, this is the Dirty Projectors’ coming-out moment. With radio singles prepped and waiting, they’re likely twiddling their thumbs in anticipation of the public’s reaction to the rest of Bitte Orca.

The irony is that Bitte Orca is theoretically, in terms of the number of disparate elements at work in each song, the most challenging record of Longstreth’s career so far. That is in of itself a feat considering the templates he’s used in the past—namely a serpentine re-interpretation of Black Flag’s Damaged and an opera composed with Don Henley as the protagonist. For the most part Longstreth has made records too obtuse for their own good; besides the small cult he’s assembled from the beginning, his prodigious output has been met with the same disdain held for the gifted kid bussed away to the accelerated school. But after listening to Bitte Orca, the entirety of his back catalog takes on a new light, as if maybe Longstreth’s been ahead of his time all this time, rather than overly clever.

Though Longstreth’s frantically confounding guitar lines have here been reduced to allow for lucidity, and his once quavering voice reeled in to a bundle of confidence, the Dirty Projectors’ sound has neither been restrained nor repackaged for an expanding audience. It’s just that the precise juxtapositions Longstreth presents tend to push the boundaries of pop without jarring the comforts of the pop song, even when these elements are completely foreign, or in the case of the mathematical tropic-folk of “Temecula Sunrise,” time signatures shift like trap doors and whole measures go missing.

The exultant township harmonies of “Remade Horizon” race in and out of focus while Longstreth’s skittering guitar fights for air. A hallmark of the album is the use of West African syncopation and polyrhythm, but never does this extract or dissuade from the joyous blend the songs accomplish. It’s a healthy miscegenation void of the cultural signifiers that might warrant it musical colonialism, and a dense head-scratcher void of the overly technical methods employed by Longstreth. Using a scalpel to dissect the jigsaw of Malian riffs, old world madrigals, trip-hop throbs, sub-bass raindrops and grungy arpeggios that make up songs like “No Intention” and “Useful Chamber” would suck the life from this celebratory record that is very much alive. In that respect, Longstreth has created Bitte Orca as a communal statement for all world ears—or something more interactive that requires one’s own voice or percussion to fill in the gaps. Regardless of the challenge level (and contrary to your appreciation of the Dirty Projectors’ past work) there’s plenty here to make you a believer.

Kevin J. Elliott

More

Thrill Jockey

Whenever someone decides to start a rock band with only two instruments, it’s always the bass that’s left out of the equation. The success of guitar-drum combos like the White Stripes and the Black Keys only serves to perpetuate the notion that the bass player is the most expendable member of the traditional rock & roll nuclear family. But Baltimore’s Double Dagger refuse to adhere to that philosophy. They view the electric guitar as little more than a studio flourish and instead allow deafening fuzzed-out basslines to comprise both the backbone and melody of the 10 combustible anthems on their third album, More.

The decision to transpose catchy power-punk guitar riffs on the much lower registers of the bass lends a dark and heavy ambience to the otherwise exuberant melodies. That interplay between light and dark also creates a tense canvas for vocalist Nolan Strals’ suitably anxious lyricism. Throughout More, Strals broadcasts the loss of clear divisions between good and evil and right and wrong, while decrying individuals who continue to embrace these synthetic dichotomies. In “The Lie/The Truth,” Strals leads an infectious scream-a-long with the lyrics “There’s no lie, and there’s no truth. There’s something in between. That’s what we do.” It may sound like a trite sentiment on the page, but rocketed out of Strals’ bleeding vocal chords it sounds like a fiercely direct battle cry against moral absolutism.

That sense of immediacy coupled with the band’s brazenly unique use of minimal elements makes it easy to forgive the album’s lack of diversity and its more indulgent lyrics. Although More may not incite a worldwide protest of guitars, its angry and infectious songs will infiltrate the head of any listener willing to acknowledge that the best guitar-playing doesn’t always have to be on six strings.

David Holmes

MP3: “The Lie/The Truth”

Jay Stay Paid

Nature Sounds

It’s been more than three years since Detroit producer James Yancey, a.k.a. J Dilla, a.k.a. Jay Dee, died of complications from lupus. Dilla had a stellar 13-year career behind the boards and as a performer, but he still had to change his handle to J Dilla from Jay Dee to avoid getting confused for fellow producer Jermaine Dupri (J.D.). And while he worked with artists ranging from Janet Jackson to A Tribe Called Quest, he never became a household name. His unconventional production style and work ethic was heralded while he was alive, but it took his death to truly shine a spotlight on his work.

Despite the fact that Dilla maintained prolific work habits up until his passing, the majority of those tracks haven’t seen the light of day. This is due to estate issues that rival that of Jimi Hendrix as far as head-scratching decision-making. Luckily the stars have finally aligned for the release of Jay Stay Paid, the first official posthumous release overseen by Dilla’s mother Maureen Yancey (a.k.a. Ma Dukes).

Jay Stay Paid has more going for it than just good karma vibes. The record was mixed and sequenced by legendary producer Pete Rock, who worked closely with Ma Dukes, digging through hard drives, floppy discs and beat tapes to put the record together. The hook is that Pete Rock is hosting a “radio” show featuring the work of J Dilla, and the result is a surprisingly cohesive record that combines unreleased instrumentals with performances from emcees that either worked with Dilla while he was alive or are sonic brothers in arms.

While the idea of listening to a “beat tape” may seem like a task better suited to chin-stroking fanboys, Jay Stay Paid is a record that even casual fans can enjoy. The genius of Dilla wasn’t in his technical skills, but in the mischievous way he chopped and manipulated sounds and songs that really shouldn’t work together. Dilla also knew how to arrange a track. Like Guided By Voices’ Robert Pollard, Dilla had the particular ability to deliver a perfect complete musical thought in under three minutes.

And when it comes to vocals, the Roots’ Black Thought and up-and-comer Diz Gilbran best capture the playful spirit of the instrumental tracks, though no one really turns in a bad performance. Hopefully Jay Stay Paid is another step towards cementing J Dilla’s legacy.

Dorian S. Ham

Flowers

Polyvinyl

Tim Kinsella is a hundred bands. The songs on the new record from his long-dormant Joan of Arc shift from bedroom synth-jams to detuned folk exercises to Deerhunter-like hymnal snips, and there’s even a pre-emo, post–Cap’n’Jazz rocker. To ask for something more consistent would be missing the point; Joan of Arc have never had an exactly easy-to-nail-down sound, nor have they come off weird in any one clear particular way. Yes, Kinsella’s voice is all over the catalogue, same with his sparse guitar noodles and jags. Yes, it will take a few listens to figure out what the hell he’s singing about, like on “The Garden of Cartoon Exclamations.” A sparse piano leads a haunting chorus underneath Kinsella’s vocals, imploring in a Jabberwocky cadence to “leave the hows and fors of things for the Nilla wafers and Cheeze Puffs.” The good old Chicago indie rock sound comes through on “Life Sentence / Twisted Ladder”—it really could be a Cap’n’Jazz outtake. The stand out of the album, though, is the first track, “Fogbow.” It beeps and boops along, mellow-like with analog keyboard tones, then the vocals come in for a verse or so before an oppressively pleasing subsonic Korg synth sound oozes in under the chorus. The overall feel of the record is reminiscent of the newest Tara Jane O’Neil album—reverb-soaked and wistful—but Flowers is a little more summery and a little less sentimental. Kinsella and the veritable army of musicians with whom he worked to make Flowers have created a cohesive record that still manages to meander all over the place, a fanciful diversion for Sunday afternoon listening.

Michael P. O’Shaughnessy

MP3: “Explain Yourselves”

ALBUM REVIEWS

Deerhunter, Rainwater Cassette Exchange EP

The High Strung, Ode to the Inverse of the Dude

Apostle of Hustle, Eats Darkness

The Disciplines, Smoking Kills

Bachelorette, My Electric Family

Federico Aubele, Amatoria

Savath & Savalas, La Llama

Grizzly Bear, Veckatimest

So Many Dynamos, The Loud Wars

Tim Easton, Porcupine

John Vanderslice,

Romanian Names

Jarvis Cocker, Further Complications

Pontiak, Maker

White Rabbits, It's Frightening