Chemical Chords

4AD

Tim Gane set out to write shorter, louder, faster tunes for the new Stereolab LP, Chemical Chords. In that he has definitely succeeded. He’s also managed to put together Stereolab’s most diverse set since the one-two punch of Emperor Tomato Ketchup and Dots and Loops.

Gane and long-time collaborator Lætitia Sadier are looking back on tracks like “Self-Portrait with ‘Electric Brain’” (which would fit nicely on 1999’s Cobra and Phases), “Neon Beanbag” (which sounds like a long-lost “The First of the Microbe Hunters” cut), and “The Ecstatic Static” (which could be either early Stereolab or late Belle and Sebastian). They’re also looking forward, getting a little darker on the hip-hop laced “One Finger Symphony” and a little more metal on “Pop Molecule (Molecular Pop 1).” The vigorous hi-hats on the title track even manage to bring to mind the late Isaac Hayes.

Check out the four-on-the-floor drive of “Silver Sands.” Those retro-synths sound familiar, and when it hits the chorus you might think it’s the mid ‘90s, except that the song’s a good minute shorter than anything on those albums. “Three Women” might best sum up the new sound of Stereolab: three and a half minutes, layers of horns, a Motown beat, a bass-breakdown and a tiny, witty hook. This track, like several others on the album, captures Stereolab in one of their strongest songwriting modes. It also captures a sound that’s closer to their live textures than any other studio recording they’ve released.

All in all, Chemical Chords is worth anyone’s time, and is a welcome step forward for one of the most persistently idiosyncratic bands around.

Matt Slaybaugh

Music Tapes for Clouds and Tornadoes

Merge

It’s bittersweet to dare call Music Tapes for Clouds and Tornadoes a denouement for the Elephant Six era, but the album’s last song, “In an Ice Palace” tends to eulogize the movement in strict and stark melodies resembling the finality of such whimsy and heat-stroked psychedelia. Though the record has been billed as the closest sequel to Neutral Milk Hotel’s long, lamented (and much discussed) In the Aeroplane Over the Sea, it is evident that nothing—even a record as consuming as the Music Tapes’ decade-later sophomore effort—should be plagued with such pressure. In retrospect, Julian Koster was the collective’s mad scientist; he introduced the singing saw, the practice of recording on ultra-vintage equipment and the childlike aesthetic distractions (this one comes packaged with a kitschy pop-out construction) that made the E6 an almost mythical existence.

He was the one always following a narrative and an unattainable, distant muse. Here it’s the saga of a personified tornado, a reindeer, a choir of singing saws (which are prominent in the ethereal, yet old-timey, interludes), and various humans who inhabit his tiny world. In the context of the turn-of-the century nostalgia—and the nostalgia of Athens circa 1997—it sounds all too familiar. Yet moments like “Majesty,” which includes an orchestra of E6 alum (Will Hart, John Fernandes, Scott Spillane, Laura Carter are all credited), radiates the communal warmth felt in the wild layers of Olivia Tremor Control or Elf Power. Most of Clouds and Tornados, though, is Koster alone with his banjo, straining his voice for maximum emotion and by circumstance draining that emotion from the listener. While certainly not what many have been hoping for (the return of Mangum), it’s indicative of what that cherished epoch in Georgia represented, as each musician had their own niche even when they all worked on the same tapestry. Koster’s is ineffably coaxing life out of inanimate objects and re-imagining our childhood storybooks to song. And here, despite modern quiescence, he’s made a timeless folk record with just enough ebullience to link him to his past.

Kevin J. Elliott

How to Walk Away

Ye Olde Records

As long as it’s been since the band had any sort of relevance, Juliana Hatfield still remains—and might forever be—a member of the Blake Babies in my mind. The idea of her making her a solo record seems a departure from her main preoccupation as a member of that band. She’s still that Boston college-rocker, collaborator of Lemonheads, store clerk at Mystery Train. I guess I need to get past the past lives still living on somewhere in my cerebral cortex, for at this point Hatfield has been making solo records much longer than she ever did those things.

Her latest, How to Walk Away, exhibits all the traits that have made Hatfield a singular talent. First and foremost, it’s that voice, a combination of come-on and lament. Hatfield can sound melancholic singing the most sunny of sentiments. Here, through just 10 average-length tracks, Hatfield—despite being into her 40s—sings in a timeless coo. “Remember November” is an obvious autumnal nostalgia trip, but her tender confessions on “My Baby...” are bluntly honest, the words of someone dealing with the tears in a relationship in a mature manner. Throughout the album, this maturity shows. These are nuanced songs far more transcendental than the collegiate fare of “Drug Buddy” or “My Sister.”

How to Walk Away seems neither out of place nor of a certain place in time. It’s the sound of honest reflection, a capable artist in full control of her array of talents. Hatfield may still seem—and sound—like someone we knew long ago, but that doesn’t mean she hasn’t made a powerful and prescient record.

Stephen Slaybaugh

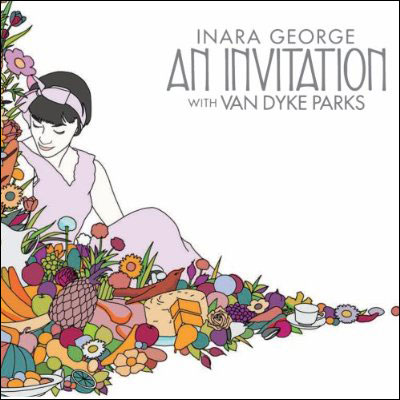

An Invitation

Everloving

Does Carla Bruni melt your heart? Did you mark the 20th anniversary of Gil Evans’ passing? Are you drowning in an indie rock whirlpool? Then Inara George and Van Dyke Parks have An Invitation for you.

Inara is the offspring of Lowell George, of Little Feat fame. That really has little to do with the record, except that Van Dyke Parks, (known primarily for his collaborations with Brian Wilson and his arrangements for super-cool songstresses like Joanna Newsom, Fiona Apple and Rufus Wainwright) was a good buddy of Inara’s long-departed father. One thing led to another and now here they are, releasing an album together.

George’s only previous solo effort, All Rise, was the kind of internet-ready electro-pop that seemed destined for the soundtrack to Grey’s Anatomy even before it landed there. An Invitation, however, is almost wholly different.

Aside from it’s glossy production, the songs on An Invitation seem almost old-fashioned. A few cuts take you straight back to yester-year, notably “Oh My Love” and “Acidental,” both of which would have been perfect for an early ‘60s Broadway musical. This flashback effect is due mostly to Parks’ orchestral arrangements, which hearken back to Bacharach, Rodgers & Hart and some of Sinatra’s fluffier moments.

On the other hand, “Dirty White” is most interesting for the tension between Parks’ loping, winds-filled arrangement and George’s lilting, alt-poppy melody. She makes like Jenny Lewis while he makes like Cole Porter.

Actually, the singer George most closely resembles is Regina Spektor, and “Idaho,” a sad story about a boy and a girl (“She tended bar in Idaho, looking for somewhere to be”), could have been lifted from one of her albums, if not for all the strings. Not that there’s anything wrong with that, but the similarities in their timbre are hard to miss. And it’s another point against an album that really wants to be a classic.

If you were the type to complain about such things, you might note that Parks’ orchestrations occasionally get so full and lush that the mix gets muddied. You might also grumble that George’s songwriting never quite rises above the pretty darn good. Or, you might just sit back and listen to that pretty voice singing those romantic lyrics over those light as air accompaniments.

Matt Slaybaugh

ALBUM REVIEWS

Conor Oberst, Conor Oberst

The Faint, Fasciinatiion

David Vandervelde, Waiting for the Sunrise

Télépathique, Last Time on Earth

Black Kids, Partie Traumatic

Neil Halstead, Oh! Mighty Engine

Falcon, Falcon EP

Andre Williams & the New Orleans Hellhounds, Can You Deal With It?

Takka Takka, Migration

Nas, Nas

CSS, Donkey

Bodies of Water, A Certain Feeling

Buffalo Killers, Let It Ride

Negativland, Thigmotactic