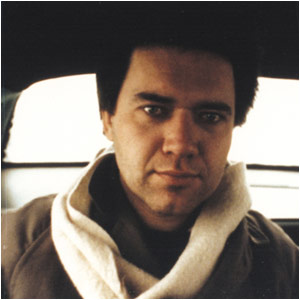

Blind Boy in the Back Seat

Columbus Discount

Any conversation regarding the primordial birth of the Columbus “sound” is for naught unless it includes a healthy volume of babble mentioning the many feats of Ron House and the two bands he launched as the ’70s were turning into the ’80s. It was a time when the line between punk and new wave was thin, and in the heart of Ohio, where Cleveland’s avant-viscerals were funneling down the Old 3C and Velvet records from a decade earlier were as awe-inspiring as the days they were released, that line was a blurry mess. In a city void of scenery and nary a landmark, House’s imprint on the cultural landscape is a monument. But monuments are built to sit in stoic quiet, so to call him such is a misnomer—the man is firmly implanted in the fabric of nearly everything that “goes down” in Columbus. It’s no accident that he currently fronts the town’s foremost punk-psychedelic supergroup, Sandwich. Active as the day he began, he’s got his fingers in every hole that allows. So much so, House-ian could easily be added to the lexicon of every half-life poised to start a band here.

Unless you were around back then, though, the Twisted Shouts and Moses Carryout aren’t likely to evoke much nostalgia. Great Plains and Thomas Jefferson Slave Apartments? Of course. But little is known about House’s earnest, yet equally as vitriolic, beginnings. As enthusiastically proclaimed by the honchos holed up at Columbus Discount, Blind Boy in the Back Seat has always been one of the label’s “fantasy releases” ever since their minds were blown by, no doubt, a well-worn hand-me-down copy of the original Old Age/No Age cassette that surfaced in 1986. The compilation, lovingly recorded, produced, assembled, and notated by Mike “Rep” Hummel and Tommy Jay, is a holy grail of sorts, the blueprint for the three decades of acerbic and distorted “campus” punk to follow. Hearing House at his most primitive on his first two undertakings plants the listener immediately in year zero. It’s easy to hear the sneering, confrontational, prankster House would become in his prime in songs like the eerie, Harrisburg-tinted ballad “Where the Windows Are,” the wonky pop of “Maps of Hell,” and the scattershot, one-stringed, dementia of “Twenty of Thirty People.” Though House is forever equated with his bratty bark—a hybrid of Jad Fair, Dave E. and Jonathan Richman—these recordings tend to magnify how influential his guitar playing would be amongst the denizens that later led Columbus into the 21st Century. Even in the brief instrumental moments of “Everyone Agrees with Me,” there’s local color teetering between ritualistic basement folk and the urgent violence of the Cleveland protos he cut his teeth on.

The biggest surprise, however, is how much this unique figure was in the same orbit of the soon to become legendary players around him. Rep goes on to hail the Twisted Shouts as “the most avant-garde group spawned in this town,” and as evidenced in the waves of white noise on “Love Yourself/Lose Yourself” or the electronically manifested squalor (provided by Chuck Kubat’s “audio-servo generator”) that runs untamed in “Statues Lose,” the Shouts undoubtedly cleared a room or two or three. Those takes, though, stand in serious contrast to the lilting psych trails he could conjure up when made to whisper or simply curb his enthusiasm. In the presence of guys like Rep and Jay (and on one track, the True Believers), he burrowed nicely under their ether. Despite that spectrum, what’s central to House is his gift to tell the tales that surrounded those nights with the ease of a hometown poet laureate. If it sounds like he’s the jack of many trades, with enough superlatives to fill a Lester Bangs rant, this is the place that cements them all. Whereas most compilations of this ilk are filled with throwaways and indulgently “lost” recordings, hearing House’s evolution is essential to eventually penetrating the exterior din and disaster of his later outfits. See this as a guide to appropriately appreciating the genius of his quotidian, yet ebullient, songwriting, which burns in the core of his music. The best part? Fade away he hasn’t.

Kevin J. Elliott

PRIMITIVE FUTURES

Hell, Yes! New Singles from Italy

All Hands Electric Singles Club Round One

Captured Tracks' International Division and the Birth of "Undie"

The Fresh & Onlys, August in My Mind EP

Introducing... Circle Pit

Nice Face, Immer Etwas

Guinea Worms, Sorcererers of Madness (4rd Year in a Row!)

Dead of Winter Singles Mixer

Introducing... Cloud Nothings

Nudge Squidfish, 20,000 Leagues Under Nashville

Night Control, Life Control

Hozac's Winter Storm

Introducing... Sweatheart

Carl Simmons, Honeysuckle Tendrals