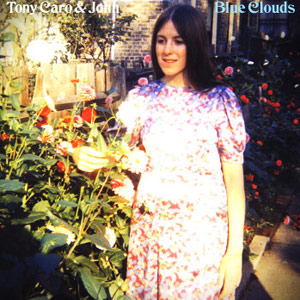

Blue Clouds

Drag City

Though All on the First Day, the one and only record by London trio Tony, Caro and John, has long been an integral piece of the ’70s British folk movement, it has remained more or less lore as few have actually heard the homespun 1972 release. And those who have heard it, fumble to find a place for it among the group’s contemporaries. Without a doubt, songwriters Tony Dore and John Clark tapped into the acid folk zeitgeist, echoing traditionalists like the Fairport Convention and the prankish madrigals of the Incredible String Band, but also the avant tendencies of Pentangle and the darkened corners of Comus. Still, even with those associations, the trio sound as if they existed outside of that time, or at least, within the insular (and unheard of in those days) world of bedroom recording. All on the First Day doesn’t take massive leaps to distance it from similar records—that distinction just happens to evolve naturally. But Blue Clouds, obviously isn’t that record (though an alternate version of the title track appears here), but an odd and sods assortment. However, it does an even better job showing the oblique paths Tony, Caro and John were taking in opposition to the bustling scene around them.

Upon first listen, there are a number of unassuming tracks that would easily place the trio among the British folk cannon. “Brigg Fair” is a Celtic downer evoking nostalgic melancholia, while “My Grandfather’s Clock,” full of bells and whistles, is the closest thing here to the Incredibles—almost to a fault. Soon, though, it is apparent Tony, Caro, and John had a much wider palette. There are subtle winks to the protest songs of Dylan and the pine-scented wanderlust of Lightfoot on songs like “Sally Free and Easy” and especially “Children of Plenty.” The latter also proves these were tunes just as informed by late-60s garage acts like, say, The Fugs. Even further beyond, the use of electric guitars becomes a noticeable difference, often times shredding and jamming their way through the album. Check out “Ton Ton Macoutes,” where it’s as if Hendrix or Randy Holden dropped in on the recordings. Despite all of these traits unbefitting of the folk of the time, the most glaring deviation comes with the group making great use of their general lack of resources, or conversely, how they adapted the technology of the time to fit seamlessly into such an acoustic-minded art form. From the outset, their primitive methods are apparent on the drumless buzzing pop bubblegum of “Forever and Ever,” and the drum machine–led sunshine of “Home.” The epic instrumental of “Fountains in the Snow,” with all of its neon oscillations and bubbling circuitry predates the electronic space-psych of Sensation’s Fix and the Silver Apples. Certainly not as amorphous as those projects by operating in the realm of folk, instead these excursions don’t distract and instead gild the songs with an alien mist. It might take awhile to get situated, but soon the realization is that Blue Clouds is not your ordinary British folk record. Even among the subject matter, it’s not even your ordinary folk record. As pastoral and calming as “Where Elephants Go to Die” may appear, Tony and John singing about “where you go when the apocalypse grows,” coupled with a wall of ominous synths is enough warning that the meadow is the last place you’d find them. Though Blue Clouds collects recordings from the trio’s entire existence (1972–77) it plays as a whole like a “lost” record finally found and adored. It sparkles as if untouched for decades, and reveals secrets that are illuminating if only because of the innovation at work during the trio’s creative peak.

Kevin J. Elliott

PAST PERFECTS

Loop

Bert Jansch, Heartbreak

Athens, GA - Inside/Out

Royal Trux, Accelerator

Crime & The City Solution, An Introduction to... Crime & The City Solution/A History of Crime: Berlin 1987-1991

The Normals, So Bad So Sad

Spain, The Blue Moods of Spain, She Haunts My Dreams and I Believe

Archers of Loaf, All the Nations Airports and White Trash Heroes

Blur, Blur 21: The Box

Can, The Lost Tapes

Sugar

The English Beat, The Complete Beat

The Guns

Lost Sounds, Lost Lost: Demos, Sounds, Alternate Takes & Unused Songs 1999-2004