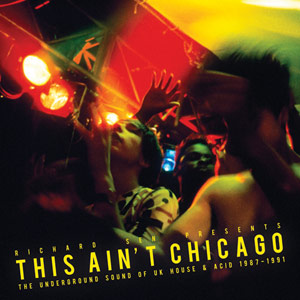

This Ain’t Chicago

The Underground Sound of UK House & Acid 1987–1991

Strut

I’ll readily admit that aside from owning an inordinate amount of New Order 12-inches, I’ve never been much of a dance music aficionado. That said, there was a short-lived period and style that captured my attention: acid house. Perhaps it was the lysergic connotations or the idealistic nature of the early rave scene, but acid house sparked my imagination when it emerged in the late ’80s. (The same was true of such seemingly unlikely practitioners as Genesis P-Orridge.) By 1988, while America was basking in the nostalgia of the anniversary of Woodstock, Britain was experiencing a true secondcoming of the Summer of Love, with ecstacy-fueled raves becoming a cultural movement. There were glimpses of acid that surfaced in the (American) mainstream (Soul II Soul), but when the phenomenon crossed the pond, something was lost in the transition, as witnessed by the morphing of acid into techno.

Fortunately, there are those that remember that brief period when acid was abundant. Richard Sen (of Padded Cell and Bronx Dogs fame) has put together This Ain’t Chicago, a two-disc compilation of tracks from 1987 to 1991. Released by Strut, who have a proven track record with these kind of comps, the release is a near-perfect encapsulation of the era, with singles from significant imprints like G-Force, Rhythmbeat, and Chill.

However, this album doesn’t start off on its best foot. Kid Bachelor’s Bang the Party released some crucial cuts of the era, but 1990’s “Bang Bang You’re Mine” isn’t one of them. The soliloquoy that runs through the song and the other vocals’ affectations make the track barely listenable. But that is the record’s only stumbling block, with the sparse R&B accents of Julian Jonah’s “Jealousy and Lies” from 1988 and Colm III’s synth-dappled “Take Me High” from 1987 being some of the earliest examples.

My only other complaint is that I wished Sen had arranged the set chronologically, as I think it would give a clearer picture of how acid house developed from the house music of Chicago and Detroit. But he no doubt was thinking like a DJ, creating a sonically cohesive mix. This is apparent by the division of the two discs. While cuts like Man With No Name’s “From Within the Mind of My 909” and Julie Stapleton’s “Where’s Your Love Gone?” feature many of the genre’s signposts (trickling basslines, highhat beats), they are moodier in temperament. And Jail Break’s “Mentality” probably owes as much to New Order as to Juan Atkins.

The second disc features bigger names in terms of commercial success, with Andrew Weatherall’s remix of Sly & Lovechild’s “The World According to Sly & Lovechild,” onetime Frankie Goes to Hollywood member Paul Rutherford’s “Get Real” and “Born in the North” by Us, whose line-up included A Guy Called Gerald. But the disc is also more emblematic of the tempos and sounds that came to define acid house. It was the atmospheric touches and general freneticism that made acid such a creative breakthrough, things that would become largely absent from techno. Such artistic innovation is perhaps most apparent in SLF’s “Show Me What You Got” and “Technological” by Bizarre Inc, one of acid’s only innovators to find success on the US charts (with “I’m Gonna Get You” in 1993). Both are prime example’s of acid’s most transcendent qualities. Unlike most other movements, acid was really confined to a time and a place, and as such, it wasn’t something that was widely experienced. Fortunately, the records still exist, as well as curators like Sen to create comps like this.

Stephen Slaybaugh

PAST PERFECTS

Silver Jews, Early Times

Codeine, When I See the Sun

Paul Simon, Graceland

Germs, (GI)

Eccentric Soul: A Red Black Green Production

David Kilgour, Here Come the Cars

We've Got a Fuzzbox and We're Gonna Use It

Medicine, Shot Forth Self Living and The Buried Life

Opeth, Blackwater Park, Deliverance, Damnation, Lamentations: Live at Shepard Bush Empire 2003

The Trypes, Music for Neighbors

Noh Mercy

fIREHOSE, Lowflows: The Columbia Anthology ('91-'93)

Doug Jerebine, Is Jesse Harper

Poison Idea, Darby Crash Rides Again: The Early Years