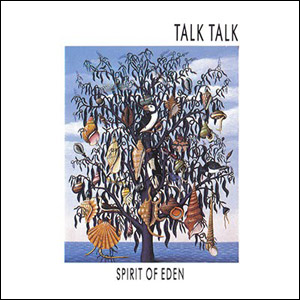

Spirit of Eden

EMI, 1988

Begun in the fashion of the electro new wave stylings of the time and hitting it big with “It’s My Life” (admittedly better than much of the ilk of the era), the title track off their second album from 1984, Talk Talk would eventually break further and further from their beginnings with each successive release. Teaming up with producer Tim Friese-Greene, who would become a permanent member of the Talk Talk fold, for their third album, The Colour of Spring, the band created their biggest commercial success, which stayed in the Top 10 of UK Album Chart for 21 weeks, while still evolving by leaps and bounds artistically.

As a result of The Colour of Spring’s sales figures, Talk Talk’s record label, EMI, gave the band carte blanche for their next recording. Barring their manager and EMI representatives from the proceedings, the band holed up in a deserted church for 14 weeks. There were stretches of time when Talk Talk was literally in the dark, playing in a candlelit void seemingly absent of time and space. Perhaps as a result and despite given ample funds with which to work, they managed to go over budget and turn in an album that they readily admitted didn’t contain any singles. EMI was none too happy, and the two parties ultimately parted ways.

But there was method to Talk Talk’s uncommercially viable madness. The resultant album, Spirit of Eden, is a largely under-appreciated masterpiece, a record whose potency has only increased with each passing year, at least to these ears. It was critically lauded upon release and writers as reputable as Simon Reynolds have credited the album as being ground zero for post-rock. But given that the band never played the record’s songs live and tSpirit of Eden never made much impact on a commercial level, I think it’s doubtful that its influence is anything so dramatic. No, this is a rarely heard gem still in need of re-examination by the masses.

It is on Spirit of Eden that singer and songwriter Mark Hollis proved his mettle, working with Friese-Greene to create a suite of six songs that are powerful when combined, but aren’t weekended by being heard on their own. The album combines Hollis’ naturally distinctive vocals with metallically resonant guitars and fiery harmonica belches. There’s as much blue-eyed soul as scorched blues and icy jazz, and when juxtaposed, these elements make for a record that seems comprised of pure emotion.

Beginning with the elongated intro of “The Rainbow,” which eventually dissolves into dewey piano pop, Spirit is sonically, if nothing else, about restraint. Each gesture is deliberate, even when saturated with noisy touches. “Eden,” which follows next, sounds like it was built from from the denouement of “Heroin,” the part where Lou Reed comes down and the part after the song that we didn’t get to hear. Its tom thumps and guitar clamor emphasize Hollis’ desperation in lines like, “Everybody needs someone to live by.” As marked by its inference to the album’s title, this is a pinnacle moment in the song cycle, and the track’s piquancy is palpable.

EMI tried to force “I Believe in You,” the second song on the album’s second side, into being a single. If any song from the record could be made to take on that form, it is this once, if only for a slightly snappier rhythm and Hollis singing more consistently throughout the track instead of in spurts. Still, this was not a record geared for radio and MTV, but rather detailed listening. There are few albums I can think of that are as subtle or as capable of so completely (and quietly) demanding of attention. “Wealth,” which ends the record, is like a modern hymnal, Hollis’ tender voice mixing with organ tones. It is a somewhat ethereal note on which to end, but this is a record that will forever be difficult to get a firm grip on, even as it continues to leave us spellbound.

Stephen Slaybaugh

PAST PERFECTS

Nick Lowe, Labour of Lust

Queens of the Stone Age, Queens of the Stone Age

Human Switchboard, Who’s in My Hangar?

Johnny Cash, From Memphis to Hollywood: Bootleg Vol. 2

Miles Davis, Bitches Brew Live

The Witches, A Haunted Person's Guide to...

Fela Kuti, "Power Show" Batch, Part II

Fela Kuti, "Power Show" Batch, Part I

Willie Wright, Telling the Truth

ESG, Dance to the Best of ESG

Sofrito: Tropical Discotheque

Squirrel Bait, Skag Heaven

Nine Inch Nails, Pretty Hate Machine

Orange Juice, Coals to Newcastle