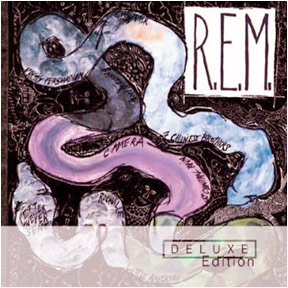

Reckoning Deluxe Edition

IRS

It’s hard to remember a time when REM wasn’t a member of rock’s grand hierarchy, when they were just the little band that could from Athens, Georgia. But just a couple decades ago—before hall inductions, before the rise to (and fall from) stadium tours, back when singer Michael Stipe had hair (and plenty of it)—REM was the great rock hope. They were firmly American, without any good ol’ boy rockist pratfalls, rooted in the underground, without being hopelessly inaccessible, and intelligent, but not too smart for their own good. They created music that was at once mythic and everyman, something borne from a quixotic equation of aspiration and a well-plied trade.

Even by the time of the band’s debut, Murmur, in 1983, REM had already begun to make a name for itself, both in sales and critical acclaim. Still, while that album was a fitting whisper of the jangled style that would come to epitomize “college rock,” with the following year’s Reckoning, the band became, well, one with which to be reckoned, unequivocally eloquent in its lyrical and musical evocations. On this album, the band divined a Southern gothic, Messrs. Buck, Mills and Berry finding new ways to connect the dots between Byrds, Big Star and Velvets, while Stipe was at both his most pragmatic and obtuse, delivering the pop equivalent of Absalom, Absalom! in miniature. (Life’s Rich Pageant would be his The Sound and the Fury.)

Like the difference between REM then and now, so too is it hard to recall what it was like hearing Reckoning for the first time 20-some years ago. I remember assuming it must be the Southern tongue of Buck’s guitar that sounded foreign, but from the first ringing notes and shuffling beats of “Harborcoat,” the band was creating a lexicon of its own, an insularity made universal. Similarly, Stipe’s imagery of fallen monuments and mixed brick and bramble were not so unlike the America of my own youth, but juxtaposed against the grandiose language more common to pop music, it too seemed alien.

While there really is not one wasted moment on Reckoning, recently reissued in a deluxe version with a second disc containing a live recording of a show from 1984 in Chicago, some remain unequalled. “So. Central Rain” seems a paean to something—forgotten cities, unresolved guilt—but it’s its vagueness that lends to an overwhelming feeling of loss. Similarly, “Time After Time (Annelise)” is lyrically comprised from dimly lit ruminations, but with such content combined with a backing that’s simultaneously intricate and primal, the song’s a small wonder of mood over content. Of course, the record is most well known for “(Don’t Go Back to) Rockville,” and deservedly so. With a plunky piano line and a simple guitar refrain, it’s not the greatest song the band ever wrote. Still, archetypically like CCR’s “Lodi” before it, the track is a barroom plea to avoid the deadend towns of the world. It may in part also be Stipe reminding himself that it’s no time to turn back—especially not when you have the future stardom that would await REM before you.

Stephen Slaybaugh

PAST PERFECTS

Pisces, A Lovely Sight

Big Star, #1 Record/Radio City

Mirrors, Something That Would Never Do

Various Artists, Smart's Palace

Miles Davis, Sketches of Spain

39 Clocks, Zoned

Company Flow, Funcrusher Plus

Nick Cave & the Bad Seeds, From Her to Eternity, The Firstborn Is Dead, Kicking Against the Pricks, and Your Funeral... My Trial

Stark Folk, Stark Folk

Dntel, Early Works For Me It It Works For You II

Cocteau Twins, The Pink Opaque

Ray Charles, Genius: The Ultimate Ray Charles Collection

Red Red Meat, Bunny Gets Paid

Chris Darrow, Chris Darrow and Under My Disguise