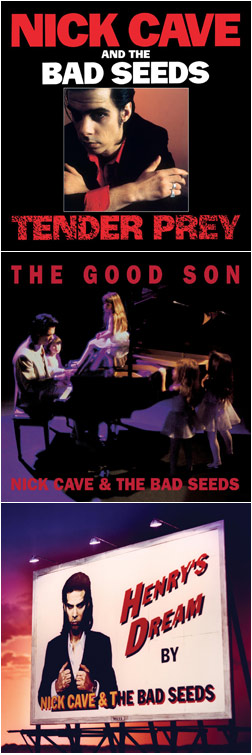

Tender Prey, The Good Son, and Henry’s Dream

Mute

Following on last year’s reissues, Mute has released their second installment of releases from the Nick Cave catalog. Like the first batch, this portion is served up in impeccable style, with each album including the original work remastered on CD and a DVD including the record in surround sound, videos, and the coordinating segment of Iain Foresyth and Jane Pollard’s Do You Love Me?, a documentary in interview form that includes past and present members of the band, Mudhoney’s Mark Arm, Matador boss Gerard Cosloy, critic Simon Reynolds, producer Flood, Suicide’s Alan Vega, and other lesser known people—pretty much everyone except Cave himself. Each set also includes extra video and audio rarities for download.

In many ways, Tender Prey, the band’s album from 1988, was both the culmination of all that had come before and the first to point to the directions they would take in the very near future. It was their last album to be recorded in Berlin, but also the first to feature guitarist Kid Congo Powers, formerly of the Cramps and the Gun Club. It is also possibly worth noting that Cave had hit rock bottom in terms of his drug use, though, as he insists in the liner notes, he has “always thought (his) particular proclivities were largely irrelevant to what (he) was trying to achieve as an artist.”

Of course, the album is highlighted by the leadoff cut, “The Mercy Seat,” made better known in subsequent years by Johnny Cash. The song is hard to ignore, with a particularly powerful inner dialogue from a prisoner on death row. That it ends in ambiguity—either concerning his declaration of innocence or his statement that he’s unafraid to die—makes it all the more powerful, Cave’s evocative telling backed by the Seeds’ ever ascending clamor. But the record is also so much more than this early climax. “Deanna” wraps a sleazy riff around Cave’s (New York) dolled-up warble of lines like, “I ain’t down here for your love or money. I’m down here for your soul.” And “City of Refuge” similarly draws its inspiration from some dark place as the band collectively chants about the song’s namesake.

Part of Cave’s principal appeal has come from calling on long traditions of song and bending them to his own warped vision. This approach became more pronounced with The Good Son, wherein he began to take on the persona of tortured torchsinger. From the opening notes of “Foi Na Cruz” (sung in the Portugese of the Brazilian locale where it and the rest of the album were recorded), Cave began constructing new modals and motifs in which to operate, essentially reinventing himself and his band as timeless arbiters. Here, he blankets his songs in parables distorted to the point of becoming more personal than archetypal, though admittedly they are that too. Musically, the album is more lush and subtle than the squalor of the Bad Seeds’ past. The centerpiece is “The Weeping Song,” which is based on a simple European children’s game, but is given an emotional weight from its patriarchal call and response. On the song, the Seeds take flamenco inflections and juxtapose them with the brooding of their pedigree. The record may at first appear to showcase a kinder, gentler version of Nick Cave and the Bad Seems, but there’s a good deal of angst simmering just below the surface.

If Cave has always worn his heart in his front breast pocket, then Henry’s Dream revealed his soul in a similar manner. There is something rambunctious about the album, and though the band ultimately had a lot of disdain for David Briggs’ production (I have to agree with them to some degree), the record captures their varied parts in a starker contrast. Kid Congo Powers and keyboardist Roland Wolf had left the band prior to the record, but here the reconstituted Bad Seeds sound bigger than they had in the past. For his part, Cave taps into his most melodramatic tendencies, almost sounding sweaty on cuts like “I Had a Dream, Joe” and “Brother, My Cup Is Empty.” It’s as if he let down some of the composure he had been building over the prior six albums, replacing that composed swagger with the spitfire of old. This is best on his run through “Jack the Ripper,” which bares little resemblance to the Screaming Lord Sutch standard.

Of course, Cave and his backing Bad Seeds have continued to morph in the eight years since Henry’s Dream’s release. (Indeed, the album only marks the midway point of the band’s discography.) But it was with these three albums that they delineated the past and the future, in many ways discovering who they were when they weren’t cognizant of it and who they could and would be. For the latter, we can eagerly await the next batch of reissues.

Stephen Slaybaugh

PAST PERFECTS

Paul Revere & the Raiders, The Complete Columbia Singles

The Jon Spencer Blues Explosion, Dirty Shirt Rock 'n' Roll: The First Ten Years

The Plimsouls, Live! Beg, Borrow & Steal

Pavement, Quarantine the Past

Fela Kuti, "Chop 'n' Quench" Batch

Buzzcocks, Another Music in a Different Kitchen, Love Bites, and A Different Kind of Tension

Frank Sinatra, Strangers in the Night

Next Stop... Soweto

Good God! Born Again Funk

Animal Collective, Campfire Songs

13th Chime, The Lost Album

Tin Huey, Before Obscurity: The Bushflow Tapes

Jawbox, For Your Own Special Sweetheart

Interference, Interference