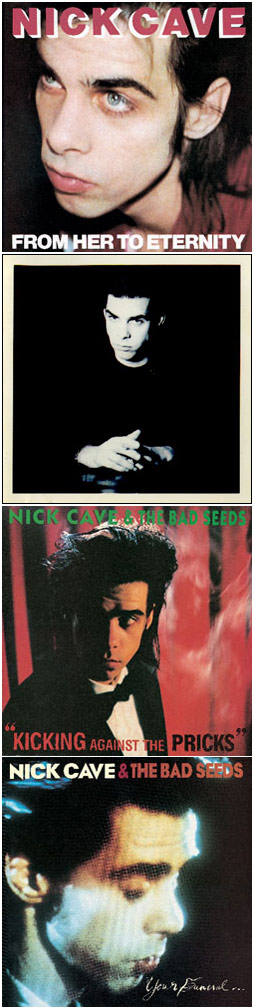

From Her to Eternity

The Firstborn Is Dead

Kicking Against the Pricks

Your Funeral... My Trial

Mute

There have been many Nick Caves over the years, and suffice it to say my Nick Cave is probably not the same as your Nick Cave. For me, he will always be the haunted warbler of the Birthday Party, a craven fiend strung out on gloom and doom. He’s certainly not the man we know today, a glorified lounge singer looking like someone’s dad. He long ago became a patsy, probably from associating with the likes of Kylie Minogue, and seems a pale ghost of his former self.

Of course there was a good span of time between the two persona, and Mute is bringing that period back into circulation with its reissues of Cave’s first four post–Birthday Party albums. It is was during this time that Cave’s affinity for Southern Gothic themes and rubbed-raw Delta Blues emerged from hinted-at fascination into a wellspring to which he has returned for the entirety of his career. With his Bad Seeds—fellow Birthday Party alum Mick Harvey, Einstuzende Neubaten’s Blixa Bargeld, Magazine’s Barry Adamson and Thomas Wydler—Cave established himself as more than just some deranged maniac let loose with a mic; he was a serious artist capable of lacing his songs with literary tropes and deconstructing rock archetypes in his own vision while still retaining an element of dementia.

Cave’s first issuance after the Birthday Party’s dissolvement, From Her to Eternity, is a record that cannot be overestimated. Here Cave coughs up a sun-baked hairball of the influences he could have just as well been digesting since birth. A cover of Leonard Cohen’s “Avalanche” begins the record, but Cave’s is unmannered and acerbic, devoid of Cohen’s poetic couture, but all the better for it. Better still is “Saint Huck,” seven minutes of Cave picking at Twain’s bones and creating a new template for Mississippi blues, one as murky as those waters, from his entrails. The album is almost enough to quell any nostalgia, and the Seeds’ feral scratchings far outweigh the grandeur they would eventually favor.

The Firstborn Is Dead is only a slightly lesser follow-up, if for no other reason than Cave’s delivery seems tempered by comparison. On this album he denotes his forefathers by name, or in the case of “Tupelo,” by location. It’s that song that leads off the record, a blustery detour from r&r memory lane. Similarly, “Blind Lemon Jefferson” rewires the blues, finding a certain amount of revelation in minimalism and Cave’s reverie.

It was with Kicking Against the Pricks that a wider audience discovered Cave’s solo work. In hindsight, it’s easy to hear the impending grandiosity on the dozen covers Cave and the Bad Seeds take on. The motifs here swing between country blues, even when reworking Hendrix’s well known paean to jealousy fueled rage, and noir-tinged cabaret. The loosely contained frenzy of Cave’s past work had largely dissipated by this point, replaced by more accomplished playing and slightly more ambitious arrangements. Though written by Johnny Cash, “The Singer” could be autobiographic, even if that would mean an inflated sense of self on Cave’s part. It’s probably not that much of a stretch, as he surely would like to be remembered with such reverence.

Your Funeral... My Trial, from 1986, is short but still sweet with Cave’s midas touch. “Sad Waters,” which leads off the album, echoes with reverb, like the band had been locked away somewhere by Phil Spector. The title track exhibits much of the same kind of ambience, and “Stranger Than Kindness” has a driving tempo that belies its haunting themes.

Of course, the albums have been given full reissue treatment as double-disc sets remastered in both stereo and surround sound with newly included B-sides and some short films. It’s the sound that matters most, as these records have only gotten better with age, but ’80s production hasn’t. Cave may not be who he once was, but these albums have remained the same—and just as captivating.

Stephen Slaybaugh

PAST PERFECTS

Dntel, Early Works For Me It It Works For You II

Cocteau Twins, The Pink Opaque

Ray Charles, Genius: The Ultimate Ray Charles Collection

Red Red Meat, Bunny Gets Paid

Chris Darrow, Chris Darrow and Under My Disguise

Beth Orton, Trailer Park

Various Artists, Downriver Revival

Isaac Hayes, Black Moses and Juicy Fruit (Disco Freak)

Death, ...For the Whole World to See

The Notorious B.I.G. Ready to Die

Zero Boys, Vicious Circle and History Of

Volcano Suns, The Bright Orange Years and All Night Lotus Party

Miles Davis, Kind of Blue

Swervedriver, Raise and Mezcal Head