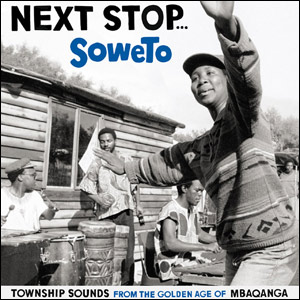

Next Stop... Soweto

Township Sounds from the Golden Age of Mbaqanga

Strut

Despite the unchecked corruption and crippling poverty that has plagued most African countries through colonialism and into the 21st century, it’s usually South Africa and the reign of apartheid that has represented the eternal woes of the Dark Continent. Be that as it may, the past decade’s effort to unearth African roots music from the ’60s and ’70s has primarily focused on Nigeria and Ghana, musics that had successfully appropriated Western funk and rock into the fabric of their respective cultures. Being witness to a renaissance of, what was for the most part, lost or unheard, and most importantly, authentic recordings from Africa, can be a dizzying undertaking. At this point, there’s so much being revealed it’s become hard to sift through it all and find the real gems. Further excavations have brought us Algerian psych, Sub-Saharan blues, Ethiopian jazz, but rarely do these compilations touch upon the boom of South Africa’s township jive.

Perhaps it has been the assumption of ethno-musicologists and Western listeners alike that South Africa was too assimilated with its oppressive Anglo influence at the time to create something as exotic as what was happening elsewhere on the continent? To some extent, the influence of Western jazz on Strut’s painstakingly comprehensive Next Stop... Soweto is not so foreign—big band horns swing in ragtime opulence, harmonicas and shuffle beats evoke zydeco, stunted rhythms align with the swagger of the best reggae—but it’s how they injected the local color and timeless tribal traditions that make this colorfully unique to the country. It was in the townships of Sophietown, in the shadow of apartheid, that this particular jive, Mbaqanga, thrived and existed until it was exploited for profit, lost the purity and became bubblegum. (There are two more albums in the series to show the evolution.) Here, though, are the fervent roots of township jive, constructed in the neighborhoods for the neighborhoods, fusing traditional Zulu vocal patterns and polyrhythm to Western instrumentation, and proliferating without the aid of radio and proper studios.

The bulk of Next Stop... Soweto is deceivingly breezy—music conceived on the spot. Whether made for late-night gatherings or sun-soaked beach romps, there’s a raw communal simplicity in the feel of each track here, though this is as linear and challenging as what their peers were producing across the continent at that time. The focal point of Mbaqanga orbits around the spiritual harmonies that circle in the center and the staccato melodies plucked out on sprightly guitars and well-worn pianos. Most township jive was celebrated for the singer leading the proceedings. Ubhekitshe Namajongosi’s “Umanduna Omnyama,” is grounded by his gruff, almost sermon-like cadence, and the choral highs of Boy-Nze Na Maqueens’ “ I’smodeni,” make for bubbling pop. Though the singers were the combined face of the music and the burgeoning stars of the community, it’s the guitars that are the heart of township jive. When the voices are cut, as on the instrumental, “Kuya Hanjwa” by S. Pilso and His Super Seven, a bright skeletal riff emerges that would make Vampire Weekend blush with guilt. Calling this stuff jazz is doing it a disservice. The “jazz” sounds like a side-note here, as if it’s intrinsic in their playing, reflective of their surroundings. The ultimate inspiration in township jive is taken from celebration, protest, and a higher power. When the song transcends to that mood, as on “Jabulani Balaleli (Part 2)” by Amaqawe Omculo, the music reaches a spiritual and equally abstract peak, making Next Stop... Soweto a necessary preservation as much as it is a survey in a social history foreign to most of us.

Kevin J. Elliott

PAST PERFECTS

Animal Collective, Campfire Songs

13th Chime, The Lost Album

Tin Huey, Before Obscurity: The Bushflow Tapes

Jawbox, For Your Own Special Sweetheart

Interference, Interference

U2, The Unforgettable Fire

Isaac Hayes, Shaft

Pylon, Chomp More

Nirvana, Bleach

Harmonia and Eno '76, Tracks and Traces

Fela Kuti, The Best of the Black President

Siouxsie and the Banshees, Juju

Gary Higgins, Seconds

Where the Action Is! Los Angeles Nuggets 1965-1968