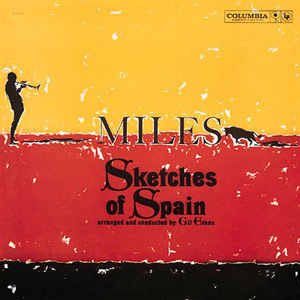

Sketches of Spain Legacy Edition

Columbia/Legacy

Miles Davis’ Sketches of Spain holds a good deal of memories for me—and not because I’ve ever set foot in the country of its title. I think I first heard this record when I was 17, coming of age and just beginning to realize that jazz wasn’t as square as I once thought, that there were musicians like Miles who were every bit as badass as my punk rock heroes. But this wasn’t an ordinary jazz record either, but something particularly out of the ordinary—even by Miles’ standards. With Gil Evens arranging and conducting a 20-some person orchestra, this was an album of a larger scope, jazz taken to the nth degree till it encompassed something greater. This was an album as narrative, so rich in mood and sound that each wordless composition seemed part of a bigger story.

For me, these flamenco-inspired sketches conjured some other world, some other time, one either long gone or simply foreign. Miles was a horn-playing matador of another era, conjuring cinematic visions of the old world, while Evans was a mid-century maestro, orchestrating the kind of record that could no longer be made in modern times. This album held an almost literary quality: Hemingway, Kerouac and Don Quixote annotated musically and etched into vinyl. More than that, made back when record labels housed their own studios full of suited session men, Sketches also symbolized a heyday of music-making, as well as that era at large: ’50s New York full of gin joints and smoke-filled diners and not douchebags and contrived hip.

Reissued and remastered to celebrate the 50th anniversary of its release (and the golden year of 1959 in general), Sketches of Spain has been given the typically great “legacy” treatment by Columbia. From the castanet-laden intro of “Concierto de Aranjuez (Adagio),” it’s hard to miss what Davis and Evans were up to, namely reshaping jazz, not into jazz to come (as Ornette Coleman did the same year), but into everything jazz could be right then. If this record is exceptionally resonant, it’s because not only does it succeed in reworking its flamenco influences, but because it’s part of a longer lineage, reaching back to the great compositions of the past century. Still, this is Miles Davis we’re talking about, and few players could color their tone with as much emotion and nuance as he could. As Richard Seidel touches on in his overly technical liner notes, it was the lyrical qualities that Miles possessed that made him unique. Amongst Evans’ arrangements, he naturally steps forward to provide the storyline or fades back into the scenery as each song dictates (best exemplified on “Solea”).

While a second disc that has alternate takes and “Maids of Cadiz” (a song recorded at the same time) satisfies some curiosities, there’s not much more that’s needed than the album itself. This is a record that continues to reveal itself to the listener, one that could be played almost daily for another 50 years without getting old.

Stephen Slaybaugh

PAST PERFECTS

Company Flow, Funcrusher Plus

Nick Cave & the Bad Seeds, From Her to Eternity, The Firstborn Is Dead, Kicking Against the Pricks, and Your Funeral... My Trial

Stark Folk, Stark Folk

Dntel, Early Works For Me It It Works For You II

Cocteau Twins, The Pink Opaque

Ray Charles, Genius: The Ultimate Ray Charles Collection

Red Red Meat, Bunny Gets Paid

Chris Darrow, Chris Darrow and Under My Disguise

Beth Orton, Trailer Park

Various Artists, Downriver Revival

Isaac Hayes, Black Moses and Juicy Fruit (Disco Freak)

Death, ...For the Whole World to See

The Notorious B.I.G. Ready to Die

Zero Boys, Vicious Circle and History Of