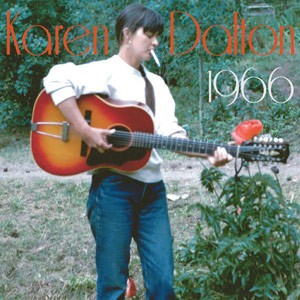

1966

Delmore

In the countless strands that connect our favorite artists to those unknown to us, Karen Dalton has had a thick web drawn to her from generations of musical history. She was Bob Dylan’s favorite singer at Cafe Wha?, but she soon gave up recording live. Similarly, she only recorded two albums (1969’s It’s So hard to Tell Who’s Going to Love You the Best and 1971’s In My Own Time), and it was unlikely that she would have recorded more had she not died of AIDS in 1993. Despite her associations, she was a true cult figure and like, say, Nick Drake, burned bright and was gone and forgotten until being reintroducted to a younger generation. She preferred a private life and private performances for friends to the role of the professional musician. Such an approach is exemplified by the intimate rehearsal recording from her remote Colorado cabin found on 1966.

Present here are versions of songs like “Katie Cruel” that Dalton fans have come to recognize. If you’ll allow me, Dalton was to Dylan’s folk scene what Shuggie Otis was to Quincy Jones’ funk and jazz scene. Otis popped with a hit, “Strawberry Letter 23,” but never realized his full potential as a recognized genre artist until the late ’90s. Dalton’s version of “Katie Cruel,” which threw her back into popularity in the early ’00s amongst the freak-folk scene, was her mark on the minds of folkies old and young. Bert Jansch recorded the song with youngsters Beth Orton and Devendra Banhart, and it’s obvious they culled their emotion from the Dalton version rather than pulling from the pre–Civil War tensions of American history. Like distant stars, Shuggie and Dalton both didn’t get their chance to shine visibly until we got a little closer to them.

Tim Hardin’s “Reason to Believe” leads of the album. It’s a pleasant surprise, because the way Dalton’s aching vocals lead the guitar through each passage is mirrored by Rod Stewart’s smash hit version off his debut solo record. Sure, it’s cute to see how clearly the pop star was influenced by Dalton, but listening to her version back to back with Stewart’s highlights the way the sullen croak in her voice adds a benumbed vacancy, a yearning for escape from the doldrums of life into the arms of a loved one, and far surpasses any other version of the song. Later, another Hardin track, “Don’t Make Promises,” appears. This song was also covered by the Beau Brummels, which you might know from the Nuggets compilations and might just draw another pretty cool string on the Karen Dalton web of connection. That steely, guarded, but heartfelt toughness is present here again in her vocal as she implores an imaginary lover to remain true: “Don’t think I’m not aware of what you’re sayin’. Is it hard to keep me where you want me stayin’? Don’t go on betrayin’. Don’t make promises you can’t keep.”

The most telling and honestly awesome moments on this record provide a voyeuristic keyhole view into Dalton’s personality and demeanor. Dalton and husband Richard Tucker’s duet, “Shiloh Town,” is a twisting banjo-led melody, with both singers trading off verse and chorus duties in rounds of lyrics about the town’s cold loneliness, and eventually, redemption. As the song ends with Dalton’s banjo, Tucker declares emphatically, “Wow what an ending! We just did it perfect!” Dalton, clearly disappointed in her partner’s exuberance over a not-so-exact take, mumbles, “No we didn’t. I didn’t know what you were doing.” From here, we get a 40-second reprise of how the ending of the song should have gone, and it may be the most beautiful 40 seconds in the history of folk music.

Michael P. O’Shaughnessy

PAST PERFECTS

Gaunt, I Can See Your Mom from Here

Alex Chilton, Free Again: The "1970" Sessions

The Lucy Show, Remembrances

Boddie Recording Company: Cleveland, Ohio

Smashing Pumpkins, Gish and Siamese Dream

U2, Achtung Baby

Can, Tago Mago

Leonard Cohen, The Complete Albums Collection

The Smiths, Complete

Void, Sessions 1981-83

Fac. Dance: Factory Records 12" Mixes & Rarities 1980-1987

Gregory Isaacs, The Ruler: 1972-1990

The Jimi Hendrix Experience, Winterland

Social Climbers