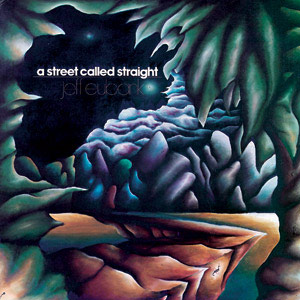

A Street Called Straight

Drag City

If it were 20 years ago, digging through the sale stacks and cut-out bins, it wouldn’t have been unusual to pass over a number of records that looked, smelled, and likely sounded identical to Jeff Eubank’s A Street Called Straight. Bad cover art, with a snapshot of a bohemian white folksman either mugging cocksure or contemplating vulnerably, private pressed in small batches and promptly given away or crammed into a dream-killing closet—A Street Called Straight in presentation alone would not pass the test. It was just another “boner” record (a term, I’ve learned, defines this type of album from the late ’70s and early ’80s) among a pile of equally unapproachable “took out a second mortgage for studio time” schlock. Even a casual listen, though, would have revealed there was a brief splash of genius embedded in the standard soft-rock trappings of the 1983 album, which would be Eubank’s only recorded work.

His story is per usual the singer-songwriters who had lost their way after ingesting what barbiturates were left from an era when Steely Dan and Fleetwood Mac still ruled the earth. Eubank immigrated to the air-conditioned, coke-infested, narcissism of post-boom Los Angeles and quickly found himself struggling as a covers man in dimly lit lounges. Not exactly thriving as the next Christopher Cross or Gerry Rafferty that he’d longed to become. Moving back to Kansas City was, at least for the sonic sake of this record, a blessing in disguise. By giving ample time for craft, what appears as an album filled with the forgotten cliches (new age lyrics, flute solos, phased acoustic guitars) of similar songwriters is actually a dark ambitious gem, brimming with invention and a freak stroke befitting other finds like Pisces or, better yet, Bobb Trimble.

A Street Called Straight is slick to the point of off-putting creaminess, and there’s little doubt on a track like “Summersong” that Eubank was heavy for Seals and Croft. Full of self-harmonized meadow-folk, Eubank was also high on the solo careers of mostly Crosby and Stills, not so much Nash and Young, as evidenced in “No Need For the Ground” and “To Make a Way,” but that was a given for the time. Where the record excels is on the songs Eubank claims “came from the ether,” not any kind of conscious songwriting. The completely leftfield synth and space sing-a-long of “Earthen Children” or Genesis by way of Gordon Lightfoot epic “Kamikaze Pilot” are companions in Eubank’s marriage of traditional exercises and slightly psychotic visions. Aliens, Mother Nature, the ambiguous power of love and adolescent daydreams all find sponsor in Eubank’s muse. Of course, the metaphysical voyage Eubank committed to his one and only masterpiece of lite psych would never escape Kansas City. Adulthood crept in even more profoundly than previously for Eubank, and the dream was gone. Perhaps it’s for the better that we’ve discovered it now, as in 1983 it may have been received with quizzical rejections. Too insular and shape-shifting for the squares, too awkward and inspirational for the heads, but priceless nonetheless.

Kevin J. Elliott

PAST PERFECTS

Destroyer, City of Daughters, Thief, and Streethawk: A Seduction

Big Audio Dynamite, This Is Big Audio Dynamite

Elliott Smith, Roman Candle and From a Basement on the Hill

Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds Reissues Part Two

Black Tambourine, Black Tambourine

Paul Revere & the Raiders, The Complete Columbia Singles

The Jon Spencer Blues Explosion, Dirty Shirt Rock 'n' Roll: The First Ten Years

The Plimsouls, Live! Beg, Borrow & Steal

Pavement, Quarantine the Past

Fela Kuti, "Chop 'n' Quench" Batch

Buzzcocks, Another Music in a Different Kitchen, Love Bites, and A Different Kind of Tension

Frank Sinatra, Strangers in the Night

Next Stop... Soweto

Good God! Born Again Funk