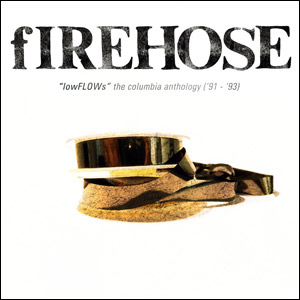

Lowflows: The Columbia Anthology (’91–’93)

Columbia/Legacy

The Minutemen have long been remembered as one of indie rock’s quintessential lynch pins. With records on the seminal SST and trailblazers as a band doing everything on its own terms, they have been held in high regard as much for how they did things as for what they did. It seems fitting that Michael Azerrad’s defining portrait of the ’80s indie rock underground, Our Band Could Be Your Life, took its title from the Minutemen’s “History Lesson—Part II” as the band’s ethos seemed to define the spirit of the time, even if neither they nor anyone else knew it.

The individuals who comprised the Minutemen—guitarist D. Boon, bassist Mike Watt and drummer George Hurley—no doubt thought the band was going to be their lives, even as they took a break from their grueling touring schedule in December 1985. Sadly, tragedy nixed those plans, with Boon killed in a car crash. Having known D. since they were kids, Watt was devastated and may have not ever picked up his bass again had it not been for a college student from Ohio, Ed Crawford. At the urging of Camper Van Beethoven, Crawford drove to California and convinced Watt and Hurley to form a new trio with him, fIREHOSE, named after the line in “Subterranean Homesick Blues” (“better stay away from those that carry around a fire hose”).

Surprisingly, fIREHOSE achieved greater mainstream success (at least on paper) than their predecessors, signing to Columbia after releasing three full-lengths with SST. They ended up only putting two albums out with the label before calling it quits, but five records in eight years and nearly as many miles on the road as the Minutemen once logged is nothing to shake a stick at. With the band reuniting this month to play a string of West Coast dates culminating with a performance at Coachella, how their legacy has translated to a couple new generations will surely become evident.

Listening to 1991’s Flyin’ the Flannel, the record seems less idiosyncratic than it once did, but no less improbable that it was released by Columbia in the days before Nevermind incited a signing frenzy. Indeed, the record’s loose stitching of ambling guitar nodes and gurgling rhythms has as much in common with the collegiate jams of Phish as the music of peers like Sonic Youth and Dinosaur Jr, so it’s hard to imagine it not finding a niche of listeners beyond the Watt faithful. Hell, “Epoxy For Example” even dabbled in worldly motifs, and “Anit-Misogyny Maneuver” wasn’t so unlike the punk-funk of the times. Then again, even Crawford’s spiel on jamming econo, “Up Finnegan’s Ladder,” mutates over the course of a minute, so there was no easy entry point to the band’s output. If the Minutemen stuck out amongst the SST roster, fIREHOSE was the black sheep in just about any context.

Live, as witnessed on the Live Totem Pole EP, included here, they were more roughshod like their indie brethren. Still, it’s not every band that covers both Public Enemy and Blue Oyster Cult in the course of one set. Mr. Machinery Operator, fIREHOSE’s 1993 swansong, benefitted from the production of J Mascis, even if the songwriting wasn’t as strong as on previous records. Crawford’s guitar sound is thicker, while vocally, there’s added husk as well. By this time, of course, grunge had taken hold of the music landscape, so it’s likely that—like many of their peers—fIREHOSE’s rockist instincts had been sparked. It’s sure hard to miss such inclinations on a track like “Blaze,” where roughneck guitars chug at a rapid pace. In some sense, this is fIREHOSE at it most conventional, but in breaking from their norm, this is also the band at its wildest and wooliest. Hearing the album now, it’s hard not to have a renewed appreciation for the record. The same could be said of fIREHOSE in general, and it’s comforting to know that the band is back to add another chapter, or at least an epilogue, to its story.

Stephen Slaybaugh

PAST PERFECTS

Poison Idea, Darby Crash Rides Again: The Early Years

Feedtime, The Aberrant Years

Roach Motel, It's Lonely at the Top

Tronics, Love Backed By Force

Archers of Loaf, Vee Vee

Metal Dance

Giant Single: The Profile Records Rap Anthology

Karen Dalton, 1966

Mighty Sparrow, Sparrowmania! Wit, Wisdom and Soul from the King of Calypso 1962-1974

Gaunt, I Can See Your Mom from Here

Alex Chilton, Free Again: The "1970" Sessions

The Lucy Show, Remembrances

Boddie Recording Company: Cleveland, Ohio

Smashing Pumpkins, Gish and Siamese Dream