“Zombie” Batch, Part II

Knitting Factory

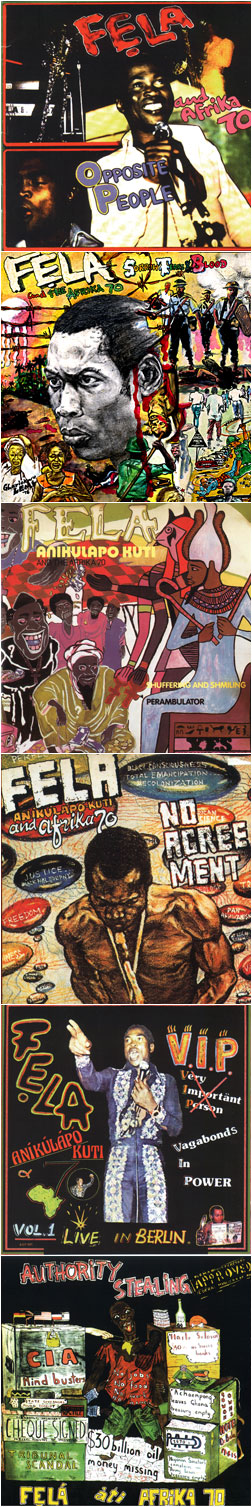

As we discussed a couple weeks ago, Knitting Factory Records recently released their third batch of Fela Kuti reissues, this one referred to as the “Zombie” batch. With nine albums on five CDs, it’s a lot of music to absorb in one sitting, and hence now we’re tackling the second half.

Another of Fela’s many releases in 1977, Opposite People is a two-song jam favoring social commentary over barbed attacks on the Nigerian government. Musically, on both the title track and “Equalisation of Trouser and Pant,” Kuti also favors his keyboard over his sax, lacing each cut’s frenetic groove with watery keyboard lines that pour over the songs’ introductory segments like molasses. He solos on his sax as well, though, transitioning into some of the longer horn parts to be found in his work. Indeed, much of his Africa 70 crew is given their own time in the spotlight. On the title track, it isn’t until 10 minutes into the song that Fela pics up a mic, singing about the contrariness of people in a rhythmic pattern. It’s one of his lighter moments thematically and works well with the song’s bouncing beat. “Equalisation” is less successful, if only for a less compelling countenance and Fela’s commentary being more obtuse.

Sorrow, Tears and Blood, also from 1977, is another two-track album, introduced with the well-known title track. Here, Fela is in top form, combining a bottom-heavy funk with lyrics that reference the Soweto Uprising of 1976 in relation to the brutality he experienced during the raids on his Kalakuta Republic home. The repetitive beats combine with his chant-like choruses of “Them regular trademark” in regards to police brutality. It is a watershed moment in his lengthy catalog, where his influences, ingenuity and intellect reach fruition. “Colonial Mentality” is less stellar, and not only by comparison. Not as concise in its melding of derision and a jazzy overtones, the song sprawls in too many directions at once.

The CD containing Shuffering and Shmiling (1978) and No Agreement (1977) is a highlight of this reissue campaign. The title track, which is one long 21-minute cut despite being labeled “Pt. 1 & 2,” is an epic moment in the Fela catalog. Consider this Kuti’s War and Peace or Moby Dick—only without the laborious passages. Here our hero plunges into a deep sea of syncopated rhythms and repeated motifs, letting the song find itself as it develops. Each passage has its own characteristics, a riff repeated for a few minutes only to never appear again, the bass suddenly taking the lead or a sudden burst of horns. By the time Fela begins to sing with an “Ah hah!” one is absorbed into the song’s insular realm so that when he says “Now, we’re all there now,” indeed we are.

“No Agreement” is one of Fela’s greatest sides solely for its loping groove, as played out on a few guitar chords. The lyrical content, a refusal to compromise, is almost inconsequential given the song’s fetching vibe. “Dog Eat Dog,” a completely instrumental cut, attempts to meld James Brown–like funk with a playful, jazz-like looseness, but subsequently fails to keep its focus somewhere along the way.

The last release in this batch pairs a live recording from the 1978 Berlin Jazz Festival (Afrika 70’s last live performance together), V.I.P. with Authority Stealing, an album from 1980. Listening to the live recording, one is immediately impressed by the immensity of the occasion. From the band’s introduction, which describes them as “the most wonderful political music that ever came out of any part of the world,” to Fela’s own explanation of how Africa is perceived incorrectly by the rest of the world (“I want you to look at me as something new that you do not have any knowledge about”), this set is extraordinary, not only for the 20-minute performance of the title track, but as an event of boundary-crossing importance. That the song itself is played with the greatest of verve only makes this recording all the more spellbinding.

Authority Stealing’s 24-minute title track is nearly as impressive. Here, Fela channels outrage at being attacked by Nigerian authorities into a cut that seems to mock the powers that be (at the time) with its ability to still sound joyful— if only musically—in the face of oppression. Indeed, that quality was one of Fela’s greatest gifts. Again and again he showed in his music that he was not to be broken as he wrapped his political rants in the most effusive bursts of jubilant sound.

Stephen Slaybaugh

PAST PERFECTS

Fela Kuti, "Zombie" Batch, Part I

Arab Strap, The Week Never Starts Around Here and Philophobia

Superchunk, No Pocky for Kitty and On the Mouth

Queens of the Stone Age, Rated R

Billy Squier, Don't Say No

Department of Eagles, Archive 2003-2006

Spur, Of the Moments

Concrete Blonde, Bloodletting

The Undertones

Oasis, Time Flies 1994-2009

The Cure, Disintegration

Shoes, Eccentric Breaks and Beats

Refused, The Shape of Punk to Come

The Jon Spencer Blues Explosion, Now I Got Worry and Controversial Negro