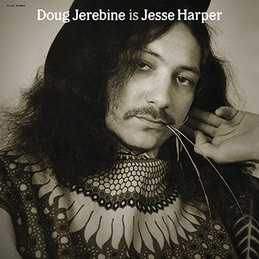

Is Jesse Harper

Drag City

With many reissues resurfacing records from the late ’60s and early ’70s, the stories of the artists behind those records are often as intriguing as the lost music. That’s certainly the case with Doug Jerebine and his instantaneous rise and fall in those halcyon days. Descended from a Maori father and a English mother and relocated to New Zealand’s North Island, Jerebine became a prodigy on the guitar before he even encountered rock music. By absorbing jazz, 78s of cowboy songs and the influence of mentor Bob Gillet, who taught him, among other things, Indian philosophy and how to play sitar, Jerebine had become a much sought after player among the burgeoning cache of garage bands in New Zealand. Eventually after successful stints with the Brew and (the now heralded) Human Instinct, Jerebine found himself in London recording with fellow countryman Dave Hartstone. Those demos, which Jerebine reluctantly recorded, caught the ear of Atlantic Records, who at the time were pining for the next Hendrix. They liked what they heard and signed Jerebine with the intent to recast him as Jesse Harper, but ended up leaving him without a record deal and the rights to his record by the time Jerebine had landed in America. Blame it on cold feet or Jerebine’s shady business associates, but the album became that of legend, never to be heard until now, 41 years later.

The Jesse Harper album more than provided the Hendrix that Atlantic was looking for. The comparisons are obvious, with Jerebine’s vocal cadence and his extra-sensory psychedelic blues playing not unlike his legendary predecessor, but Jerebine was much more, with a persona as distinct as any artist of the time. “Ain’t So Hard to Do” is emblematic of his style. It’s filled with a heavy monolithic tone, which surely acted as a force field to distance himself from the front his handlers wanted him to present. As much as Jerebine digs into Southern boogie and the country-tinged troubadour motif on songs like “Ashes and Matches” and “Thawed Ice,” he couldn’t have possibly made a dent in the mainstream Woodstock crowd. His music was just too amorphous and mysterious. Jesse Harper is warped by a miasma of rich psychedelic textures and hints of Eastern ragas, the occasional flash of jazzy percussion, and oddball narratives. As traditional as “Hole in My Hand” and “Circles” come across, as soon as Jerebine launches into his sinewy solos, you get the feeling his underground status as a guitar god is warranted. It’s a style on par with other lost heroes of the guitar world like Terry Reid and Randy Holden.

Alas, if there’s one thing to glean from Jesse Harper, it’s that Jerebine wasn’t cut out for—or in want of—the limelight. Soon after the disaster with Atlantic, Jerebine resigned from public playing and instead rejoined Human Instinct as a songwriter and spiritual guide. That band’s now classic Stoned Guitar displays the lasting influence of Jerebine’s style and tone twofold. Yet, even that wasn’t enough to keep Jerebine itching for success. He eventually became enlightened by Hare Krishna and retreated to India where he has been ever since. There have been the occasional one-offs, where Jerebine has joined long-time companions in nostalgic jams, but none of it has been as lucid and transcendent as the Jesse Harper sessions. Hopefully, with a new audience being introduced to this record, Jerebine will extract himself from his miserly existence and reward his listeners with a few more lost chords.

Kevin J. Elliott

PAST PERFECTS

Feedtime, The Aberrant Years

Roach Motel, It's Lonely at the Top

Tronics, Love Backed By Force

Archers of Loaf, Vee Vee

Metal Dance

Giant Single: The Profile Records Rap Anthology

Karen Dalton, 1966

Mighty Sparrow, Sparrowmania! Wit, Wisdom and Soul from the King of Calypso 1962-1974

Gaunt, I Can See Your Mom from Here

Alex Chilton, Free Again: The "1970" Sessions

The Lucy Show, Remembrances

Boddie Recording Company: Cleveland, Ohio

Smashing Pumpkins, Gish and Siamese Dream

U2, Achtung Baby