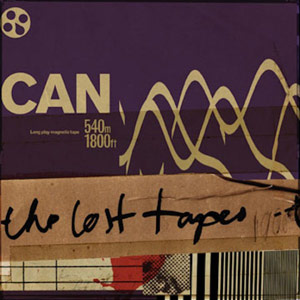

The Lost Tapes

Mute

The recent excavation of more than 30 hours of untouched Can was surely a eureka moment for keyboardist Irmin Schmidt and the band’s official archivist, Jono Podmore, when it was found abandoned in their Weilerslist studio. But for listeners, even though it’s been whittled to the three-disc Lost Tapes boxset, this discovery only adds to the enigma that was Germany’s most forward thinking band. Ever since its inception, Can has always been a dicey proposition. Either you believed in their alchemy—a rockist take on psychedelia, jazz, and avant-garde tropes that defined the bedrock for the new frontier better known as Krautrock—or what they did came across as a foreign language. The push and pull they exerted between moody and frenetic extremes was as experimental as they come. They were breaking boundaries, or as Podmore put it in a recent email exchange, they “opposed the banal copyism” that existed in post-war Germany and “digested European art rock and African-American music and tried to turn it into something new.” Podmore insists that in organizing the endless reels, which were filled with the building blocks that would inform classics like Tago Mago and Ege Bamyasi, what remained and appears here was picked because of quality. “There were a few pieces that made it through the net on the basis of their documentary value,” he says. “But the bottom line was, is it good enough as a piece of music, regardless of sentiment or history?” That said, after sifting through three hours of outtakes, soundtrack detritus, and choice live takes, instead of opening some doors as to how Can evolved, you begin to understand why much of this never made the cut.

Presenting both Can’s beginnings with Malcolm Mooney and the shift to Damo Suzuki, the first disc of the Lost Tapes is the real treasure. The 10-minute “Waiting for the Streetcar” may be the set’s most visceral moment, tapping “Sister Ray” as a blueprint for some quintessential Can jamming. Or perhaps it’s the explosive motorik chug of “Millionenspiel,” which shows the group firing on all cylinders. If there were an essence of Can, this would be it. Elsewhere, tracks like “Your Friendly Neighborhood Whore” and “Bubble Rap,” show Can as tireless pioneers of their own sound. Much of what’s intriguing here are nebulous experiments, rubbing primal blues up against reggae, fusion dabbling with mechanical funk, and avant-noise morphing into challenging psychedelia. But again, as Podmore says, “Can considered themselves a work in progress, improvising in a very conscious and organized way,” and that is more than apparent in the set’s exhaustive grooves. A lot of the tracks that were salvaged are simply germs and fragments that eventually blossomed into the Can we know and love. “On the Way to Mother Sky” is the jam that begat “Mother Sky,” and the lengthy, intricate “Dead Pigeon Suite” ends in an epiphany that would become “Vitamin C.” So in many ways these tracks don’t exactly stand alone, though they do provide a look at the innards of the Can clockwork. If that prospect is enticing, than there’s plenty to dig into among the Lost Tapes dizzying selections. It’s also telling that Can may not have wielded as much organic magic as once thought; letting the tape roll to snatch up every little bit of their evolution reveals them as more studied and less loose. Still, there’s no denying that what Podmore and Schmidt have assembled is a gargantuan undertaking, and though a bulk of this material is non-essential, it’s vital in telling the story of one of music’s greatest mysteries.

Kevin J. Elliott

PAST PERFECTS

The English Beat, The Complete Beat

The Guns

Lost Sounds, Lost Lost: Demos, Sounds, Alternate Takes & Unused Songs 1999-2004

This Ain't Chicago

Factrix

Silver Jews, Early Times

Codeine, When I See the Sun

Paul Simon, Graceland

Germs, (GI)

Eccentric Soul: A Red Black Green Production

David Kilgour, Here Come the Cars

We've Got a Fuzzbox and We're Gonna Use It

Medicine, Shot Forth Self Living and The Buried Life

Opeth, Blackwater Park, Deliverance, Damnation, Lamentations: Live at Shepard Bush Empire 2003