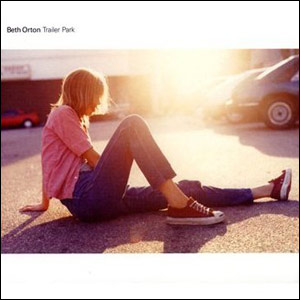

Trailer Park: Legacy Edition

Arista/Legacy

Before its release in 1996, few could imagine the breathtaking fusion of decidedly British folk and trip-hop beats and atmospherics that would mark Beth Orton’s debut, Trailer Park. Bert Jansch and Massive Attack were worlds (and decades) apart, but Orton drew equally from both those camps, constructing a record as ambient as it was intricate, as emotive as it was steely and ethereal. Orton might have spearheaded a new movement, much like the one that happened in Manchester earlier in the decade, if anyone had been brave enough to follow her lead. Few were, and other attempts at bridging the same gap came off hackneyed by comparison.

That may be overstating it a bit, but this album did have that sort of potential, as did Orton’s follow-up, Central Reservation. As it was, though, it was simply a brilliant record shining bright in a landscape of Brit-pop detritus. From the opening breath of “She Cries Your Name” (the record’s first single), Orton is revealed as a distinct talent, but just as importantly, she was also possessed with the unique wherewithal to enlist Andrew Weatheral to morph several of the record’s cuts from the raw folk that was her lifeblood into something entirely different. On the first of these, “Tangent,” Orton’s voice seems cast adrift in the abyss, her ruby vocals reverberating off of flanged tones and beats. In contrast, “Touch Me With Your Love” is more anchored, its bass thuds and syncopated rhythms rooting Orton’s voice in something more earthly. Funnily enough, though, the best of the Weatheral cuts is the one that shows his hand the least. For the most part, he leaves Beth on her own as she reinterprets the Ronettes’ “I Wish I Never Saw the Sunshine.” Funny because this, of course, was a golden opportunity to try on Spector’s wall of sound, but he was wise enough to let a good thing enough alone.

But Trailer Park is more than these three songs, and more than Weatheral’s post-production work. “Don’t Need a Reason” is another cut that shows Orton at her most translucent. Here, her wispy vocals move across a lilt of strings and fingerpicked acoustic, turning her melancholy majestic. It’s a simple song at heart, but it becomes much more detailed as the parts swell together. “Galaxy of Emptiness” ends the album proper in a more transient realm. Here the electronics go jazzy, creating the kind of groove a quartet might conjure. Orton’s voice doesn’t enter until midway through, and when she sings, “There’s a galaxy of emptiness,” she could be describing the disorienting vibe of the song itself. From here, she could have gone anywhere

But this edition doesn’t end there, tacking on a second CD of B-sides and EP rarities. Enlisting Terry Callier, Orton found a kindred soul; in the ’70s he had fused folk and jazz in a manner much like her own mixing of styles. Fittingly then the best from this collection come from the Best Bits EP on which he contributed. “Dolphins” and “Lean On Me” place his honeyed vocals amongst a mixing of fiddled violen and Ayers-esque vibraphone. Still “I Love How You Love Me,” a Barry Mann cover contributed to the Mojo soundtrack, outshines them both, Orton giving the song standard stature.

Trailer Park perhaps hasn’t reached the rank of other records considered more seminal, but listening over it once more, it’s evident how singular the album is in both sound and the persuasiveness of its sentiments. Orton found a niche centered squarely between two counter-running strains, and in doing so, created songs that transcended their stylistic habitats as much as they drew from them.

Stephen Slaybaugh

PAST PERFECTS

Isaac Hayes, Black Moses and Juicy Fruit (Disco Freak)

Death, ...For the Whole World to See

The Notorious B.I.G. Ready to Die

Zero Boys, Vicious Circle and History Of

Volcano Suns, The Bright Orange Years and All Night Lotus Party

Miles Davis, Kind of Blue

Swervedriver, Raise and Mezcal Head

Flipper, Generic, Gone Fishin', Public Flipper Limited, and Sex Bomb Baby!

Pavement, Brighten the Corners: Nicene Creed Edition

The Grifters, Ain't My Lookout

Blue Ash, No More, No Less

The Jesus and Mary Chain, The Power of Negative Thinking

New Order, The Collector's Editions

Kevin Ayers, What More Can I Say?