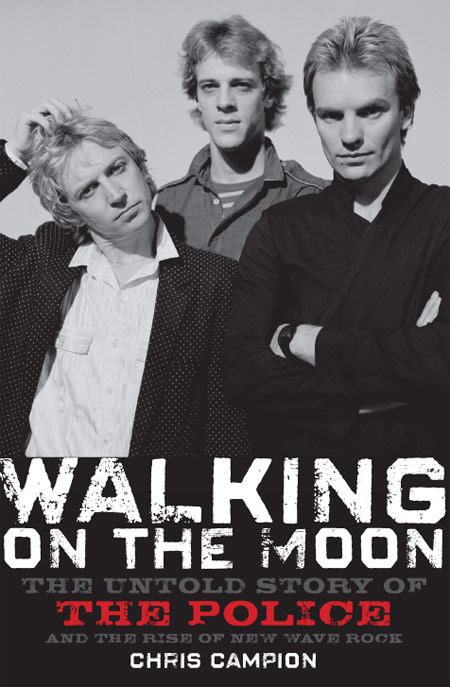

by Chris Campion

Wiley

In Chris Campion’s new biography, Walking on the Moon, it seems a little ironic that it’s the Police that come out looking like the bad guys. But the fact that all three members of the band seem driven by fame and fortune (instead of artistic accomplishment), and that the band’s career was largely orchestrated by über-capitalist Miles Copeland III, the head of IRS records and drummer Stewart’s older brother, helps explain why the band faltered during the punk explosion of ’77/’78, only to rise to prominence during the era of Thatcherism and Reagonomics. Campion ties all this neatly together in Walking on the Moon, which is as much Miles’ story as it that of his sibling’s band, and eventually devises a solid hypothesis for what he calls “the Rise of New Wave Rock.”

Campion’s treatment of the Police is even-handed, to say the least, and if the trio comes off poorly (which it does) it is the fault of their own egotism (not to mention a little xenophobia and an inability to bury grudges). Campion interviewed Stewart Copeland and guitarist Andy Summers for the book, as well as various associates, but Sting wasn’t as cooperative. Still, Campion finds evidence of his ego outweighing the worldly image he’s since painted for himself. In describing the band’s appeal in 1979, he’s quoted as saying, “I am married, I have a kid—what girls get with the Police is real sexuality. The Bay City Rollers was jerking off. Kiss me quick. With the Police you can actually get fucked.” That the peroxide blonde singer was referring to the band’s teenage female fans is more than a little uncomfortable. Summers for his part comes off jaded and old, which he nearly was when the Police started—only now he’s in his sixties. In his memoir written 30 years after the band took a slagging at the hands of NME writer Paul Morley, he is clearly still bitter, saying that Morley “writes well enough, although mostly with a morbid narcissism.”

Though Campion does make some embarrassing blunders (Greg Ginn was in Black Flag, not Big Black), the book is mostly an astute take on the music industry at the time, the Police’s place in it and Miles Copeland’s manipulation of both. As he puts it, “Just as the Police found their footing in the free enterprise culture of Thatcher’s Britain, new wave established its foothold during the Reagan era, with its bellicose politics and its brash promotion of America and American values, both at home and abroad.” Like new wave, the Police had embraced something of the punk aesthetic (Miles had shared an office with the publisher of notable punk zine Sniffin’ Blue) and DIY business model, but were dismissive of its brash sound and sometimes even brasher politics. While perhaps more organic than what is commonly thought of as new wave these days, the Police were a similarly safely watered down and commercially viable version of the punk polemic.

Ultimately, both Copelands, Summer and “the Sting” (to quote Morley), come off as little more than fashionable interlopers, as much as Campion tries to sing their praises whenever applicable. The book reveals a callousness that in retrospect undermines the cred that they culled from (purposefully) adapting the DIY work ethic of their luminaries. It’s a fascinating revelation, one that draws back the curtain on a seeming rags-to-riches story. Campion should be applauded for not pulling any punches, even when the hits are self-imposed by the Police themselves.

Stephen Slaybaugh

Soul Power

Prefuse 73 Live Review

Best Music Writing 2009

Sid! By Those Who Really Knew Him

Bomp! 2: Born in the Garage

When Giants Walked the Earth: A Biography of Led Zeppelin

The Devil Went Home and Puked: Robert Pollard's Rock Show

Skinny Puppy and Surfer Blood Live Reviews

Light: On the South Side

Eccentric Soul Revue Live Review

The Stooges: The Authorized and Illustrated Story

The Velvet Underground: An Illustrated History of a Walk on the Wild Side

Echo and the Bunnymen and St. Vincent and Andrew Bird Live Reviews

Faust and Os Mutantes Live Reviews