Drag City

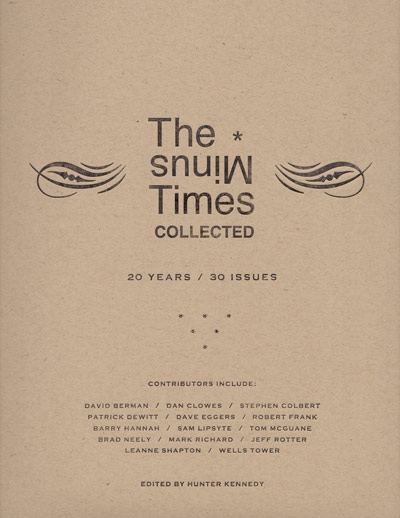

During the ’80s and ’90s, the zine was a vital cog in the mobilization of a counter-culture that was unplugged from the usual media outlets of the time. Be it thriving scenes of punk, metal, goth, indie or industrial, rambles from poets and pundits, factoids and propaganda from cultists, vegans and animal rights advocates, all used written words upon a page, cut and pasted with minimal funds and minimal experience, stapled and sent via snail mail, to get their message out of the underground and into to a far wider consciousness. Anyone born into the Google-able cyber-stream might find such an exercise fruitless and actually wasteful, seeing as we are spoon-fed endless bits of meaningless and meaningful information from even the most obscure reaches of the globe at an instantaneous rate. But for many the zine is a lost art. There’s a reason (beyond nostalgia) I still have back issues of The Offence and Moo, catalogs from Burning Airlines, and Zendik Farm recruiting pamphlets stored in tubs somewhere in the basement. There’s a reason even though The Agit Reader is a website on the internet, we strive to base our aesthetic in this forgotten realm. It’s because we appreciate something more than links, pull-quotes, and regurgitated press releases in our daily lives. That’s an edict Hunter Kennedy acknowledged when he started The Minus Times way back in 1992. Thankfully Drag City has recognized the wealth accumulated in the 20 years since Kennedy meagerly started the zine, and has collected all 30 issues into one deluxe package.

Though The Minus Times focused very little on music—think of the zine’s hodgepodge of surreal fiction, irreverent lists, deadpan humor, oddball illustrations, and existential interviews as a precursor to McSweeney’s Quarterly—there is certainly a punk ethos at work in Kennedy’s design. Little has changed since he began with Issue #1, which was a “one-page open letter crammed with stories and strange news clippings as well as occasional dispatches from the far corners of America,” other than the cache of his contributors and the length. Going chronologically back from the most recent issue, every piece is still torn from Kennedy’s 1922 Underwood typewriter, formatted by hand, and left with the foibles of an editor with an overloaded mailbox, which include misspellings, scribbles in the margins, and off-centered photocopies. Intentional or not, it lends an earnestness that is indeed missing in modern times. As for the content, it’s quite an undertaking to ingest this treasure trove in even a few sittings. I can only suggest flipping through and sticking on something that catches the eye. The collection is something you can come back to repeatedly without being bored by repetition, always stumbling upon a writer who emerges with a voice that at once feels familiar, but becomes a name you’ll start searching for on the bloody internet. There are selections from (now household names) like Dave Eggers (before he was responsible for the aforementioned McSweeney’s) and artist Daniel Clowes, and repeat prose from lesser-knowns (but no less important) scribes like personal favorites Hudson Bell and Brad Neely and plenty of musings from Kennedy himself.

The Minus Times eventually started to intersect with the music world, and many notable musicians soon began giving regular contributions, including poems from the Silver Jews’ David Berman, fiction by way of Royal Trux’s Neil Michael Hagerty, and interviews and mixtapes from the likes of Stephen Malkmus and Chan Marshall. If you were a record geek in the advent of indie rock, you’re sure to find a personality from that time you’re dying to read talk about their “last meal.” Giving specific weight to any one piece would be taking from the joy of discovery that should come for anyone encountering The Minus Times for the first time. Internet be damned, with an anachronism as hefty, unknown and inspiring as Kennedy’s Minus Times Collected, I might be logged-off for the rest of the year.

Kevin J. Elliott

Love Rock Revolution

September Festival Guide

Great Plains, Directions to the Party

My Morning Jacket Live Review

The Zombies and The Left Banke Live Review

King Khan and the Shrines Live Review

DJ Brad Hales

The English Beat Live Review

El-P Live Review

July Festival Guide

Northside Festival and Destroyer and Wintersleep Live Reviews

The Clean and The Cult Live Reviews

George Harrison: Living in the Material World

June Festival Guide