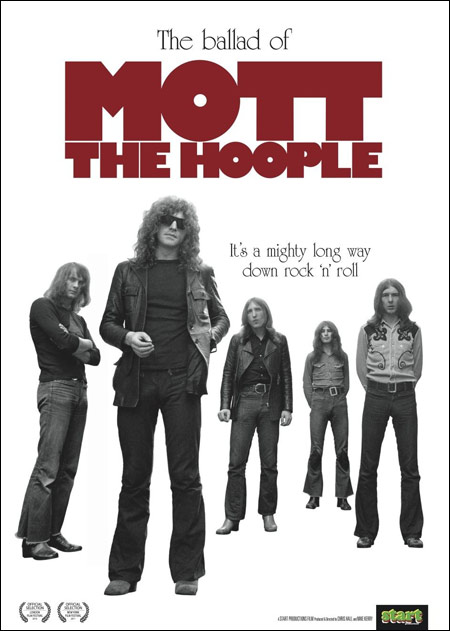

Redeye

The Ballad of Mott the Hoople is really a tale of two bands: the working class lads from Herefordshire, England who specialized in rhythm and blues boogie rock only to find modest success, and the mannish, glammed-up arena act that followed with a bigger-than-life facade. The documentary’s array of talking heads—from The Clash’s Mick Jones to Queen’s Roger Taylor—never settles on which side of Mott the Hoople was preferred, but it does consistently contend that the band was always ahead of the times and should be regarded among the heavy hitters of the British pantheon. Mixing a bounty of recently found footage of the group’s tumultuous career climb with a thorough retrospective provided by members past and present, director Chris Hill doesn’t rely on the stylized pomp that defined the band to tell the story. Rather, he allows the Mott saga to unravel in earnest, like a poignant love letter, warts and all.

It’s Mott’s origin that’s most intriguing. Discovered and guided by Guy Stevens (most noted for producing London Calling), the early version of Mott reflected the madcapped impresario’s love of American music. From Sun recordings to Motown and onto Dylan, Mott had the chops to pull off the Americana revue, and with Stevens’ addition of Ian Hunter to front the band, they became a well-regarded live act in the Northern UK, despite the lack of a hit record. Little is known about the band in this stage of their career, but the film gives details of how Stevens’ wild fancies never really gave them a voice during that period. There were highs (the punk precursor Brain Capers) and lows (the country-hippie disaster Mad Shadows) among the early catalog, and here each phase is met with an honest perspective (none of it was very good). None of that mattered once Stevens’ involvement dissolved and the rigors of touring forced the band to retire prematurely.

Mott the Hoople 2.0 is the version most of us know. Not yet a star in the States, long-time admirer David Bowie urged Mott to regroup, even giving them a couple of songs (the first being “Suffragette City”) to lift their spirits. The transformation of Mott came with the Bowie penned “All the Young Dudes,” where they instantly went from out-of-work working class slogs to critical darlings and the new face of glam. Though Mott had their biggest worldwide success under the tutelage of Bowie, the irony was they had become a parody of what they once were. Certainly not as theatrical as their glam peers, they no less sold themselves with the extravagance of the genre because, as Hunter claims, “everyone was doing it.” The problem lies in the shadow of Bowie, as “All the Young Dudes” became their only calling card, and most of the music made after that (largely written by Hunter) suffered in a vaudevillian camp. They may have had the chutzpah to proclaim themselves one of the world’s biggest bands, but their output pales in comparison to the true monsters of the time, like Queen, the Rolling Stones, and Ziggy Stardust himself. What is gleaned from this film is that Mott had a hand in shaping the ’70s style regardless of their status as poor man’s stadium rock. Despite that underdog attitude, history repeated itself, as inflated egos, rock & roll excess, and the addition of Mick Ronson (at Hunter’s bequest) drove the band to another implosion. Whether or not you were a fan, or in the case of most commentators in the film, willing apologists of Mott’s outrageousness, it’s hard not to smile at Ian Hunter’s confessional candidness. His remembrance of Mott celebrates the bawdy antics and gimmicky veneer of the band, but it also admits that enough was enough. Hunter was never one to bow to labels and producers for the almighty pound, and his constant head-butting is the reason for their demise. If anything, The Ballad of Mott the Hoople portrays a cautionary tale about a lifestyle that really no longer exists, and the full extent of British cult love for a shoulda, coulda, woulda band that probably doesn’t deserve the treatment and accolades they get over the course of 90 minutes.

Kevin J. Elliott

Lindsey Buckingham Live Review

Scratch Acid Live Review

Def Jam Recordings: The First 25 Years of the Last Great Record Label

Beats, Rhymes & Life: The Travels of A Tribe Called Quest

Put the Needle on the Record

The Karaoke Singer's Guide to Self-Defense

Are We Still Rolling?

Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark Live Review

The Raincoats Live Review

!!! Live Review

1991: The Year Punk Broke

September Festival Guide

The Jesus Lizard, Club

Retromania