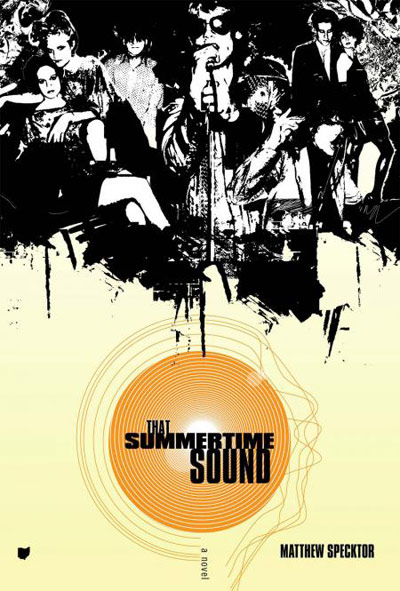

by Matthew Specktor

MTV Press

For those of us who had our first experiences with rock & roll crammed into the clubs and scouring the record stores that populated the strip of Columbus, Ohio’s High Street between Blake and King, the setting of the new novel from Los Angeles–based writer Matthew Specktor will seem immediately familiar. Set amongst the record bins of “School Daze” records, at the booths of “Perry’s” bar, and the dance floor of “Crazy Lady’s,” That Summertime Sound, as the title indicates, is a search through those dilapidated confines for a sense of place and meaning.

The book follows an unnamed narrator who is convinced by a friend, Marcus, to spend the summer of 1986 in Columbus on a quest to find the Lords of Oblivion and their singer Nic Devine. The band and the few 7-inches they self-released have become something of an obsession, and our hero makes it his mission to see the band play live at least once before the summer ends. While the Lords and the city of Columbus itself take on mythic qualities before the college chums even make it past the outerbelt, the narrator, and in a larger sense, the book itself, continues to propagate, rather than dispel, such urban mythology as further cultural heritage is revealed.

”My thought would be hopefully it’s not puncturing a mythology,” Specktor told me when I spoke to him on the phone. ”In the end, the idea behind the book is it’s necessary to mythologize a place to want to live there, that on some level we all create mythologies about the cities that we’re living in. Sometimes they’re exciting and invigorating mythologies, and sometimes they’re deadening mythologies. There’s no shortage of horrible, dulling mythologies about LA, for example. My feeling is that when one’s life is interesting or successful, you have one foot in that enlivening mythology all the time.”

Of course, Columbus has had its share of near mythical characters over the years as well, and half the fun of reading the book is spotting them. Gary Hauser, a clerk at School Daze and singer for the Plains States in the book, is obviously Ron House of Great Plains and Thomas Jefferson Slave Apartments fame, and the character Knobby is surely based on Daniel Ash, who used to date a Columbus girl and supposedly wrote the Love and Rockets song “Mirror People” about the patrons of Crazy Mama’s (Crazy Lady’s in the book). Reference is also made to zine The Attack, Agit inspiration The Offense in real life.

“One of the things that horrified me a little is that everything in the novel has an impulse toward cartoonization,” Specktor said. “The figures in the book who are based on actual people are steeply exaggerated in one way or another. I felt bad that I had to make Nic Devine and the Lords of the Oblivion be the only great band in Columbus and all the others horrible, at least according to the narrator. It was not true of my Columbus experience, and I’m actually a big Great Plains and Slave Apartments fan.”

Specktor was evidently a big fan of the Boys from Nowhere as well, as they were his inspiration for the Lords of Oblivion. But where the narrator eventually gets to see his idols play, Specktor never had the same luck in real life. “They were never active when I was in Columbus,” he recalled. “They were active in the sense of releasing a couple 45s while I was around, but whenever I was in town, Mick (Divven) never had a band together.”

It is when the narrator finally witnesses his heroes in the flesh playing live that is the book’s pivotal moment. Everything that the whole summer has hinged upon rests in that club: Will the band succeed? Will he get the girl? (Forgot to mention there was a girl, but there’s always a girl, right?) And will he even actually see the band play?

“The whole concert sequence is pretty funny to me,” Specktor explained. “While writing it, it was purposeful for it to feel more hallucinated than real. I hope it does. It’s like... on the most basic mechanical narrative level, you are telling a story and this concert is either going to happen or it’s not going to happen. It’s a yes or no question, like most narrative questions are. So the question becomes for me as a writer is how do you fulfill that contract without just being ‘I saw the band and they were fantastic,’ end of story and we ate cake and happily ever after? There’s a sense of the event being something he both gains and looses. You see it and you miss it at the same time.

“That’s part of the whole bargain of art,” he continued. “We go to art to give us these distillations of experience that tend to fly right past us or through us when we live them. It doesn’t matter what those are. One’s experiences of love or one’s experiences of anything tend to feel kind of vaporous, and art gives us that concentration and we have to be willing to accept that concentration without imagining it being presented to us as an actual substitution.”

One gets the sense that much of what happens in the book passes by the narrator or that he’s not even all that much there. “It developed as a point of strange urgency that the narrator not have a name,” recalled Specktor. “Not just to be coy or invent some deniability, but because he’s a strange absence in the middle of the story. You get a tiny slice of his other life, but he’s not seen and is barely described physically at all. He’s a void of sorts.”

It is this conflux of ideas of identity, place and memory that give the book its resonance and make it more than just an idle story about goose-chasing some band around. Instead, it reads like a coming of age story, or perhaps more accurately, a coming of drinking age story, where everyone is forced to find a home, a city, a band, a person or at the very least a moment to call his own.

Stephen Slaybaugh

Dan Deacon/Deerhunter/

No Age and Gang Gang Dance Live Reviews

Björk, Voltaic

A Cultural Dictionary of Punk

Pitchfork Music Fest 09 Wrap-Up

Man Man Live Review

Scott Walker: 30 Century Man

Michael Jackson 1958–2009

Robin Trower Live Review

Isis Live Review

Depeche Mode, The Dark Progression

Yeah Yeah Yeahs Live Review

Metal Machine Music: Nine Inch Nails and the Industrial Uprising

King Khan and the Shrines Live Review

Chrome Cranks Live Review