Sony Pictures Classics

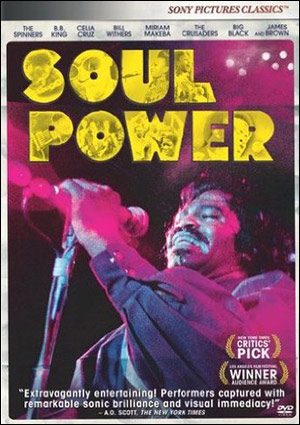

Working as editor on When We Were Kings, the Academy Award–winning documentary of “The Rumble in the Jungle,” the 1974 heavyweight championship fight between Muhammad Ali and George Foreman in Zaire, Jeffrey Levy-Hinte discovered another story that was left on the cutting room floor. There had been a corresponding concert engineered by the boxing match’s promoter, Don King, of great symbolic importance, and which also happened to be an astounding event in and of itself. As director, this is what Levy-Hinte sought to reveal with Soul Power, released theatrically in 2008 and on DVD and Blu-Ray last week.

The three-day music festival, billed as “Zaire ’74,” was conceived by African musician Hugh Masekela and concert promoter Stewart Levine not just to coincide with the boxing match, but to further emphasize the underlying theme of a return to the homeland by pairing African-American artists with their African counterparts. While the fight was eventually delayed to take place six weeks after the concert, Ali’s presence and the impact on both the city Kinhasa, where the event took place, and all that were involved make this latter connection vividly poignant.

Culled from hundreds of hours of film, Soul Power captures both the tenacity of the event’s organizers as well as the unbridled joy this symbolic pilgrimage instilled in all the musicians. While the clips of Ali and King grandiosely waxing on the significance of what they’re about to accomplish puts Zaire ’74’s impact in terms of red and black, there’s greater resonance to be found in the expressions captured candidly on the performers’ faces. The 13-hour plane ride is not an arduous battle with boredom, but an endless celebration, as the musicians jam while expectantly making their way to Zaire. Their excitement is palpable, and it carries over once the musicians leave the plane, not just with those playing, but into the streets of Kinhasa as well.

What Levy-Hinte and, of course, the original film crew capture is the natural kinship between the American and African musicians and the African denizens. One sees little difference between the street-corner bands of Kinhasa and those playing on the chartered flight. Similarly, the three days of performances, which ran the gamut between American artists like James Brown, BB King, and Sister Sledge and African performers like Trio Madjesi, Mirian Makeba, and Tabu Ley Rochereau, flow from one to the next, emphasizing the music’s shared heritage.

For all the film’s, albeit light-handed, social commentary, it is still the event itself that is the focal point. While each performance is top-notch, particularly BB King’s rendition of “Thrill Is Gone” and Celia Cruz and the Fania All Stars’ “Quimbara,” one can clearly discern both the concert and the movie mounting to a climax as James Brown’s headlining spot draws here. And the Godfather doesn’t disappoint. Backed by the JBs, he is in top form as he dances and struts while leading the band through “Payback” and, ultimately, “Say It Loud (I’m Black and I’m Proud), which appropriately closes the film. It is this final song that brings everything full circle, showing what was really at stake here—not money or fame or even accolades from fan or critic—but rather a shared heritage. And in that way, as Soul Power vividly shows, Zaire ’74 was surely a success.

Stephen Slaybaugh

Best Music Writing 2009

Sid! By Those Who Really Knew Him

Bomp! 2: Born in the Garage

When Giants Walked the Earth: A Biography of Led Zeppelin

The Devil Went Home and Puked: Robert Pollard's Rock Show

Skinny Puppy and Surfer Blood Live Reviews

Light: On the South Side

Eccentric Soul Revue Live Review

The Stooges: The Authorized and Illustrated Story

The Velvet Underground: An Illustrated History of a Walk on the Wild Side

Echo and the Bunnymen and St. Vincent and Andrew Bird Live Reviews

Faust and Os Mutantes Live Reviews

Passion Pit and Austin City Limits Music Festival Live Reviews

Yo La Tengo and Arctic Monkeys Live Reviews