The Bell House, Brooklyn, September 7

by Stephen Slaybaugh

Over the years, Steve Albini has proven himself to be of a prickly type, the sort who doesn’t play the music industry’s reindeer games or suffer fools gladly. While many thus take him to be some kind of asshole, I’ve always admired his honest approach, which seems to just reflect a hardboiled Midwest personality. One would think, though, that as he’s aged Albini might become an old crank, calling out bullshit at the most innocuous of offenses. But while the opposite hasn’t happened either, Albini has seemingly stopped paying the rest of us much mind and just gone about his business. That business has seemed to focus more and more on his job as head engineer at Electrical Audio, his recording studio in Chicago, and less on making records or touring with his band Shellac. The band’s only released two albums this decade and performances outside of the Windy City have become fairly infrequent.

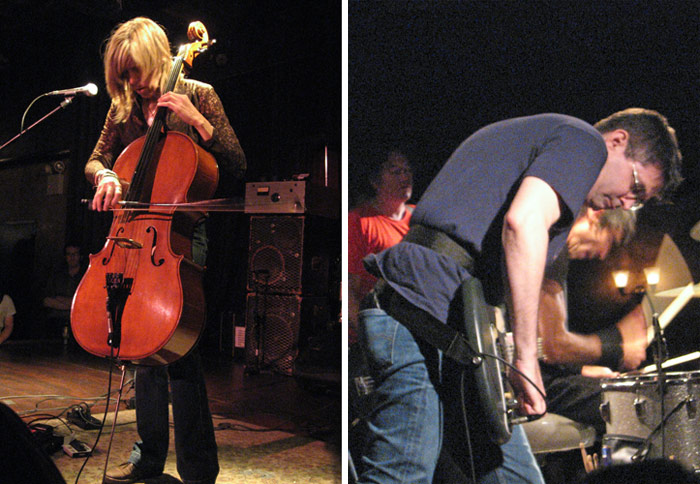

But having come east to play All Tomorrow’s Parties New York, the band scheduled some dates to coincide with the trek. Joining them for this short tour was Helen Money, the stage name for cellist Alison Chesley, a former member of Verbow. Opening the show, it was quickly apparent that Money’s MO is much different that the approach taken with Verbow. Where once Chesley’s cello was folded into the rock of Verbow, now taking centerstage, it was manipulated with rock effects (delay, flanger, reverb, etc.), but output a caccophonic din that was distinct as it was rockist. How many times have we seen someone take a bow to a Stratocaster? Too many of course, and here Money did the opposite by utilizing a strangely rare technique of playing the fretboard and four strings like some guitar. Sampling and looping herself while also applying other triggered effects, the half dozen or so instrumentals she created were just as visceral as they were cerebral, if not more so. By the third “Untitled” song, Money had proven that this wasn’t some avant garde recital, but rather just a case of kicking out the jams with an unlikely instrument. The crowd was won over by the end of her set, as she surely tapped into some of the same synapses that Shellac is known to fry.

Shellac—Albini on guitar, Bob Weston on bass on Todd Trainer on drum—transitioned from Money’s set instrumentally before delving into “Copper” and “Compliant,” a Weston-sung bout between the bass and guitar that the band has been playing out for a couple years without recording. The band was all business for the first third of the set, with hardly a wink to the sold-out crowd as they ran through “Be Prepared,” “Canada,” and “A Minute” (among others) with an aplomb derived purely from the veracity of their songs and their emittance from their no-frills set-up. Eventually, as they are wont to do, they opened it up to questions and answers. The best query was whether or not Steve was wearing a calculator watch, to which he replied that we was, but not the good one.

The set turned out to be a lengthy one, and cuts like “Prayer to God,” wherein Albini ad-libbed about baby Jesus getting off his ass for once, showed his wit to still be as sharp as the steely riffs he was playing. “Wingwalker” and “The End of Radio” were other highlights. While Albini paced his corner of the stage and Weston bobbed here and there, Trainer was the most animated. Each hit of his drums was accented by a contorted facial expression. He was the rhythmic equivalent of a welterweight boxer, a sweaty blur of precision jabs and uppercuts to his toms and cymbals followed by snare cracks. The show eventually ended unceremoniously: they came, they played, they rocked—and that’s all that was needed.

The Wexner Center, Columbus, September 7

by Kevin J. Elliott

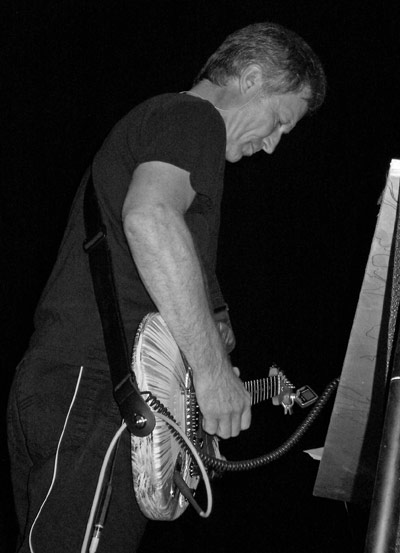

Krautrocksampler, the legendary tome written by Julian Cope and usually referred to as the bible to the influential genre formed by counterculture Germans in the late ’60s, certainly regards Neu! with the same regard as it does the other heavy-hitters from the time (Can and Kraftwerk), but only gleans over the importance of Michael Rother and Klaus Dinger forming the duo. In a BBC documentary released not long ago, the subjectivity of Krautrock is explored in reflections from the people who made it, subsequently placing a sort of hierarchy as to who was making this music with the purest intentions. You’d be hard pressed to part me from any record in Cope’s list of essential records, even if I have been indoctrinated with a different reality of what “really” went on and why. Years later we come to find out Amon Duul were just communal terrorists who later had money on the brain. Kraftwerk were caught up in the man-machine more concerned with product and image than creating soulful music. Can were stoned most days and way into the Doors, and Faust were simply freaks for freaks sake (and still maintain that persona). In hearing Rother’s take on the tumult that came in Germany’s “hour zero,” you get the feeling he was the only true visionary of the bunch, sonically building a new German landscape with his spacious tones, minimal guitar scribbles, and Dinger’s (before then unheard of) motorik heartbeats.

It would’ve been greedy to ask for more from Rother’s performance as Hallogallo, a trio including Sonic Youth’s Steve Shelley in place of Dinger (who passed away in 2008) and the Tall Firs’ Aaron Mullen on bass handpicked to play selections from the catalogs of Neu! and Harmonia (Rother’s equally innovative, if less definitive, side-project). It didn’t, of course, sound as it may have emanating from a Dusseldorf train station in 1971, but Rother assured it was the closest replicate he could craft. Back then it was mountains of analog equipment, knobs and levels, but now Rother relies on a laptop to work as the music’s canvas. Still omnipresent, though, are his improvisational guitar trips, each little journey bouncing around the room as if searching for an apex of melody and experimentation. This is definitely a live show that’s not for those looking for much of a connection with the performers, instead its music that lets the mind wander in endless directions. In that same BBC documentary, a shirtless Iggy Pop, drilling open coconuts on an unnamed beach, expounds upon the innate powers hidden in that first Neu! record, calling it a “pastoral psychedelism” one can use to speak with his own mind. That testimonial might be Pop babbling without a filter, but experiencing those electronically formed structures at the feet of their creator is something to behold. Rother could have very well took this tour on the road by himself, pre-loading everything down to those spontaneous guitar shreds onto a hard drive and warping the atmosphere with his neo-Theremin. Shelley look strained at times keeping the clockwork rhythms in check and Mullen was little more than an afterthought in his role, but without them the performance would have lost a certain depth. The center of this universe was, without a doubt, Rother’s stoic alchemy, as even when those seemingly infinite grooves carried on, they sounded as fresh and invigorating as they must have more than 40 years ago.

Rush Live Review

Neil Hamburger, Hot February Night

Clinic Live Review

Devo Live Review

Rush, Beyond the Lighted Stage

Pitchfork Music Fest '10 Wrap-Up

Here Comes Your Weekend Parking Lot Blowout Live Review

Tristan Perich, 1-Bit Symphony

Touch and Go: The Complete Hardcore Punk Zine '79-'83

A Live Evening with MGMT

The World Cup Top 10

Five Hundred 45s

Jello Biafra and the Guantanamo School of Medicine and Chrome Cranks Live Reviews

David Cross, Bigger and Blackerer