by Simon Reynolds

Faber and Faber

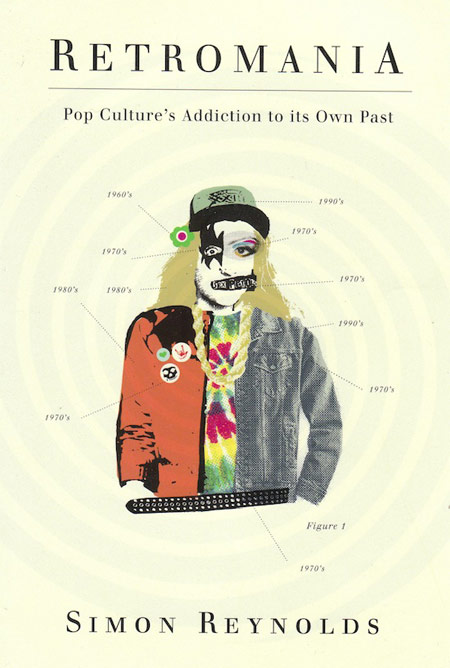

For anyone with the faintest of interest in pop music—and more broadly, pop culture—the title to the new tome by Simon Reynolds, author of one of the most engrossing music histories in book form, Rip It Up and Start Again: Postpunk 1978–1984, immediately resonates. Retromania: Pop Culture’s Addiction to Its Own Past is an examination of this past decade’s tireless recycling of the decades past and their cultural ephemera.

Only, as Reynolds explains, in the naughties (i.e. the 2000s), there is no cultural ephemera. Every artifact—whether trendy or overlooked during its time—from the past century has cultural currency. And while ideas of “retro” and “vintage,” as well as pop revivals like mod and trad jazz, sprung up in the latter 20th century, at no other time has so much of the past existed than the present. In fact, Reynolds ultimately argues that there has been a dearth of new ideas this decade, particularly in pop music, because so much of the past has been recirculated. As he sees it, aside from the minor blips in British rave culture of grime and dubstep, the first decade of the new millennium has been devoid of innovation and filled with recycled styles and sounds (see freak folk, emo, electroclash, etc.). And he’s right.

Of course, evidence with our current obsession with the past has revealed itself in other ways. The most obvious is the glut of bands reuniting. Though Reynolds himself has largely avoided reliving the music of his youth with his middle-aged contemporaries, he seems to side with the Stranglers’ Hugh Cornwell when he said, “We’re all tribute bands now. If you play the old catalogue, you’re a tribute band.” He sees the trend of bands reuniting and/or playing albums from their back catalog in their entirety as tied to the museumification of rock & roll, as well as the bizarre phenomenon of re-enactments, in which participants take painstaking measures to recreate specific moments in rock history like Bowie’s last gigs as Ziggy Stardust.

Reynolds goes on to show how these manifestations of cultural recycling are directly linked to the digital age and the rise of the internet. YouTube has essentially become an archive of pop visuals like concert footage and videos that were once confined to the instances they appeared on television or to bootlegged VHS tapes. Now, all those moments in pop history are at our fingertips. Similarly, recordings that once were hard to fine are now just a Google search away. In this way, everyone now has instant access to all manner of audial and visual documentation that was once a rarity.

It is the gluttony of information and stimuli that is crowding out new ideas. When once the limitations of money and space caused one to be selective about music purchases, the internet now provides an endless trough of sounds past and present at which to feed for free. And with the boom in reissues and boxsets, as well as the new economics of being a working musician, it is no wonder that current releases make up only about a third of the music purchased each year.

Ultimately, though, one might wonder why there is any cause for concern. As Al Gore tells us, recycling is a good thing, and besides musicians have always borrowed from the past, right? But in addition to byproducts like third-rate records being exalted for only their obscurity, the real dangers that Reynolds sees are the “directionless direction” and “febrile sterility” (both terms he borrows from other sources) of the current musical landscape. For those still looking for a “future-rush” (Reynolds’ term), it is becoming increasingly difficult to hear something utterly unique and new.

Reynolds ultimately seems optimistic, which is a relief given the depth in which he goes into our current obsession with the past. Retromania is packed with both the symptoms and the causes of this affliction. Reynolds doesn’t confine himself to music, but shows how similar fetishes with the past have surfaced in fashion and other forms of modern culture. His densely woven argument takes into account all manner of technological influences—from samplers to iPods—and cultural shifts, intricately revealing the many roads that have lead to where we are now. Though the book ultimately leaves one not feeling nearly as optimistic as the author, one is still bewildered by Reynolds’ skillful dismantling of the predicament.

Stephen Slaybaugh

Mid-Summer Festival Guide

Tedeschi Trucks Band Live Review

Wild Nothing and Twin Sister Live Review

Fungi Girls Live Review

Bob Mould, See a Little Light

Are We Still Rolling?

Northside Festival

The Indie Rock Poster Book

Blank City

Times New Viking Live Review

Aesop Rock, Danzig, and the Antlers Live Reviews

The Feelies Live Review

Surfer Blood Live Review

The Naked and Famous Live Review