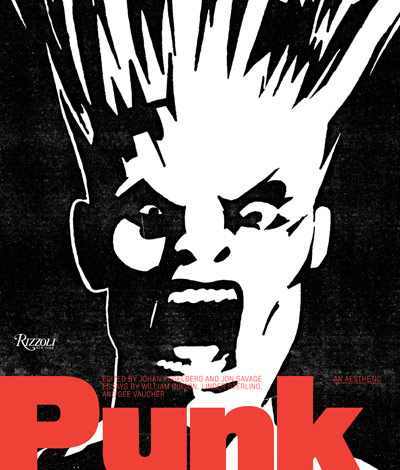

Edited by Johan Kugelberg and Jon Savage

Rizzoli

Before it became commercially commodified into a simplified mishmash of safety pins, mohawks and anarchy symbols, punk was as much about its wide range of visual signifiers as it was a kind of music. Taking cues from a wealth of influences ranging from Dadaism to pulp fiction, the aesthetic of punk was a pastiche loosely held together like so many torn t-shirts. The artwork found on flyers, fanzines, and the covers of singles and albums was as important as the many three-chorded songs in communicating the themes of nihilism, black humor and reappropriation in which punk reveled. And, of course, clothing and other fashion choices were at one time of great significance as a means of disassociating from the norm—until the norm absorbed them as accouterments of rebellion easily accessible at any mall.

It is this visual identity that Punk: An Aesthetic explores. Edited by Johan Kugelberg and Jon Savage, who have a similarly themed exhibit, Someday All the Adults Will Die: Punk Graphics 1971-1984, on view currently at the Hayward Gallery in London, the 352-page book presents a swath of imagery from before, during and after punk’s apex in 1976/1977. As Kugelberg, who recently founded the Cornell Punk Archive and has curated punk-themed exhibitions for the Steven Kasher and Boo-Hooray galleries in New York, states in the book, “The history of the punk aesthetic cannot be told, only shown.” To wit, through 500 images, the volume attempts to do exactly that, linking its many record covers, fanzines, flyers, photographs, and other ephemera through their visual language.

“Here, in presenting this book, Johan Kugelberg is pursuing what he does,” Gee Vaucher, visual artist and founding member of Crass, states elsewhere. “He collects, conserves, shares, and publishes historical evidence of a moment in history.” Indeed, punk may have been a moment that has already passed, or perhaps it is a moment, as Kugelberg suggests, that is continuing to be experienced over and over again by new generations. That remains up for debate, but it’s impossible to ignore its lasting cultural currency. Besides, it may be besides the point. “What constitutes the punk aesthetic? How did it come to be?” Kugelberg asks. “Does any of this matter? Did Luke know that Darth Vader was his father previous to his arrival? Did Malcolm McLaren invent punk? Did Ron House?”

Savage, who is best known as the author of England’s Dreaming: Sex Pistols and Punk Rock, expresses the belief that just as important as punk’s musical influence is its philosophical legacy, specifically the DIY approach it espoused, which has become so ingrained in youth culture these days as to be indiscernible. “Punk was primed for a samizdat economy: only that way could you find out what was really going on,” he says. “Punk fanzines opened up a whole image bank of possibility... and also fed into what remains the period’s most lasting achievement: the idea of do it yourself.” This assertion is backed up by examples from Sniffin’ Glue, Touch and Go, Noise, Slash, Search & Destroy, and Bored Stiff. As the book progresses, it’s hard not to miss the Xeroxed connection between such periodicals and Jamie Reid’s tabloid appropriation in his work for the Sex Pistols, Linder Sterling’s cut-up artwork for the Buzzcocks, and the flyers for gigs by the hardcore bands of the ’80s.

But punk was many things to many people, and the book’s myriad graphics reflect this plethora of ideas. Neuromancer author William Gibson shares his own personal discovery of punk, which consisted of connecting the dots between the Velvet Underground, Patti Smith, the Sex Pistols, and the music he heard at a club in Toronto. That is really how Punk: An Aesthetic reads, as the lines between punk’s factions scattered geographically and chronologically. Gibson describes not first hearing singles by the Sex Pistols, but seeing them, and the “shock of the new,” which he says can’t happen in today’s digital age, “Today we know what new things look like before we encounter them physically,” he asserts. “Usually we know what they’ll look like before they even exist.”

Of course, there is also some discussion of punk’s commodification and examples given like a Sex Pistols baby onesie. But largely that argument is left alone, as simply entering the discussion of authenticity is part of the punk experience. Instead, Punk: An Aesthetic is presented as a barrage of artifacts and imagery that suggest that the movement was as important as any other cultural shift in human history.

Stephen Slaybaugh

Public Image Ltd. Live Review

October Festival Guide

The Minus Times Collected

The Jesus and Mary Chain Live Review

Love Rock Revolution

September Festival Guide

Great Plains, Directions to the Party

My Morning Jacket Live Review

The Zombies and The Left Banke Live Review

King Khan and the Shrines Live Review

DJ Brad Hales

The English Beat Live Review

El-P Live Review

July Festival Guide