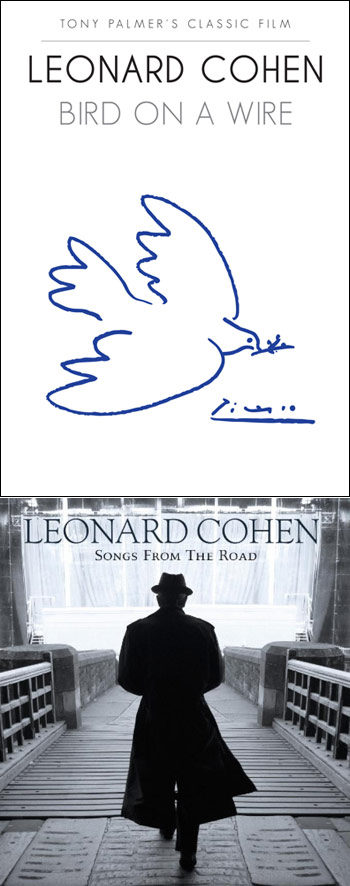

Bird on a Wire

Voiceprint

Songs from the Road

Columbia

While Leonard Cohen has enjoyed a career in music for more than 40 years (and as a poet even longer), he has seemingly shied away from the spotlight for a good portion of it. Until 2008, it had been 15 years since Cohen had toured and his releases had been intermittent over the last decade. In fact, from 1994 to 1999, Cohen had been in seclusion at a Buddhist monastery.

But then perhaps that has always been part of Cohen’s appeal: the recluse with the graven face and gravelly voice. Add in his taste for the poetic and his talent for dimly lit portraits of heroines and misfits, and its easy to understand his magnetism and legend.

Two recent DVDs look to reveal something of the Cohen mystique—or at least something about the power of his stage presence. However, shot more than 35 years apart, Bird on a Wire and Song the Road actually show a very different performer, even when he is playing the same song.

Bird on a Wire was shot by Tony Palmer, who was hired by Cohen’s manager at the time, Marty Machat, to film his 1972 European tour. Palmer originally edited the film himself and was set to sell it to the BBC when Machat nixed his final cut. (Machat had financed the project.) The manager asked Palmer for all the raw footage, and had the film re-edited and tried to release it to theaters after the BBC rejected the new version. It was only shown once in London and then seemingly disappeared off the face of the Earth. Palmer hadn’t even kept a copy of his version for himself, but last year 294 cans of film were found in a Hollywood warehouse. Much of the footage was damaged beyond repair, but with a good set of sound dubbing tracks, Palmer was able to put together a version of the film well representative of his original vision.

In 1972, Cohen was 38 and at one of the many peaks of his career. While in the U.S. he was mostly known as the author of Judy Collins’ “Suzanne” (her cover was a hit in 1966), he was much more more popular in Europe, with each of the three albums he had released at this point—Songs of Leonard Cohen, Songs from a Room and Songs of Love and Hate—making it into the UK Top 10. The film opens with Leonard inviting fans at a concert in Tel Aviv to come closer to the stage. Unfortunately, they’re greeted by over-eager security guards, who Cohen then admonishes for their brusqueness. It is indicative of the tour as a whole, as Cohen deals with blown speakers in Berlin (prompting him to improv, “Speaker, won’t you speak for me?”) and gradually starts feeling like he is unable to give his audiences a worthy performance the more he sings them every night. He seems to shun the adoration of his audience, just as he literally turns away some very forward offers from several female fans. You can feel his weariness, but he is wrong about the quality of his performances, with versions of “Suzanne” and “Sisters of Mercy” being particularly poignant. In Jerusalem, where he tells the audience that the show is the “last one (he’ll) be doing for a long time,” he cuts the performance short and only returns to the stage after a quick shave cheers him up. He’s still a wreck by the show’s end, crying backstage from both happiness and emotional exhaustion.

During one scene in Bird on a Wire, when asked by a French reporter how he measures success, Cohen says that “success is survival.” He was referring to how long it had taken him thus far to mount a career, but his comment is also prophetic. That is obvious when watching Song from the Road, a compendium of 12 songs recorded at 11 different concerts around the world. Curiously also beginning in Tel Aviv (with “Lover, Lover, Lover”), the film shows that now in his mid-70s, Cohen is now a confident performer. Where once his younger self worried about his audience’s comfort and the honesty of his singing, Cohen now comprehends the puissance of his persona and the power of song. With his voice now a darker and rougher tone, Cohen is these days more a torch singer than the folky chanteur of his youth. “Chelsea Hotel,” which he also sings in Bird on a Wire, is now smoked with raspy tones and fuller backing. And “Suzanne,” though its simple melody is still at its heart, is filled with angels’ breath. One can see and hear the 38-year-old in this wrinkled (but dapper) visage, but Cohen’s come to possess something else that once escaped him. It’s an intangible quality, but one can see the grandeur in his every gesture, the transcendence to be found in his musical offering. His success may be his survival, but his survival has been through his songs.

Stephen Slaybaugh

Shellac and Helen Money and Hallogallo 2010 Live Reviews

Keep on Running: The Story of Island Records

Rush Live Review

Neil Hamburger, Hot February Night

Clinic Live Review

Devo Live Review

Rush, Beyond the Lighted Stage

Pitchfork Music Fest '10 Wrap-Up

Here Comes Your Weekend Parking Lot Blowout Live Review

Tristan Perich, 1-Bit Symphony

Touch and Go: The Complete Hardcore Punk Zine '79-'83

A Live Evening with MGMT

The World Cup Top 10

Five Hundred 45s