MVD

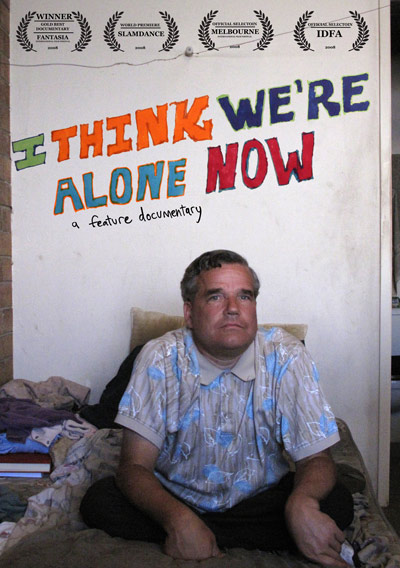

Given the ubiquity of documentaries in these hand-held digital days, there are an increasingly number of “directors” that simply stumble on some weirdo and their dysfunctional family, slap some salacious scenarios together, and go straight to DVD for portfolio purposes. Sean Donnelly, director of this sad, quite unsettling stalker story, made the wise decision to keep his portfolio-proper to 61 minutes. To drag it further might’ve stretched its intentions to freak show proportions. Sprung from the TMZ-ready tale of Californian Jeff Deane Turner—the blink-of-an-eye infamous stalker of ’80s pop star, Tiffany—I Think We’re Alone Now solders on another intense Tiffany fan, Kelly McCormick, an inter-sex individual from Denver.

Turner, and his two good friends who are brought in briefly, are the more classic high-functioning autistic types who can rattle off insane amounts of information and historical knowledge and joke of their lack of social skills. Turner’s “conversion” to Jesus is the usual flim-flam—or not, as he audaciously announces to his congregation that he mostly saved souls at a porn convention where Tiffany was appearing and that “Tiffany is the most Christ-like person (he’s) ever met.” His outlook—however addled by Asperger’s Syndrome and repressed abuse—is a startling affront to the phony baloney churches always peddle. Near the end of the movie, when Turner seems to be finally moving on from Tiffany (to Alyssa Milano), he is almost redeemed from his scandal sheet past.

McCormick is an even sadder study. Claiming, “I have the usual monthly cycle like any woman, even Tiffany,” she is on massive amounts of testosterone suppressants, and yet constantly talks of her athletic prowess and makes frequent pro football references. (Yeah, I know, lesbians like football sometimes.) McCormick fell into an accident-induced coma in her early 20s, dreamt of a woman who looked like Tiffany while in the coma, and was given a Walkman with a Tiffany song on it the moment he came out of the coma, and thus believes she’s destined to be with the singer.

If you’re already gobsmacked that there are two such incredibly intense Tiffany fans in the world, keep a bucket near the couch. In perhaps the most depressing scene, we see the admonitions of a number of seemingly “regular” Tiffany fans at an outdoor beachfront concert extolling the greatness of the mouse-voiced also-ran. Having the dough to actually use Tiffany’s hits in the film might’ve underscored this strange devotion. (Not to mention that the incidental soundtrack music is pretty uselessly “tortured.”) Of course as with any such stories, there’s no accounting for taste. And there’s no end to discovering how important a crappy one-hit wonder can be to an individual as they age far way from their developmental youth and closer to harsh, adult-awakened truths.

Donnelly tries to make visual connections between the two Tiffany-ites. They both wear fanny packs; they both had military dads; they’re both on disability. Well, probably a lot of mentally challenged people in their latter 40s could claim those traits. The way these two people “meet” was obviously a set-up, but then aren’t we all used to these “reality” shenanigans, to the point of expecting them? Whatever the manipulations, the ending scene of a Tiffany concert in a cheap gay club in Vegas is heartbreaking in a most unexpected way.

Asperger’s Syndrome wasn’t officially recognized as a certified diagnosis until about 1995. Had this documentary been viewed before that, who knows how this film would come off. As it stands—illustrative fonts, shaky modern digital camera “work,” desperate attempt to go out there and find some freaks to base a documentary on so as to get funding for a future, more involved documentary—this film has the whiff of the slumming hipster trying to disguise a condescension conundrum that goes back at least as far as Wesley Willis CDs.

Given that “queer cinema” is now a genre, this film finds a few new bends in that often dark and lonely road. It’s become easy to think that because a few sitcoms and cable fashion shows have out characters that all is getting right for closeted people. I Think We’re Alone Now is the kind of flick that might make you wonder about every person walking past you on the street and what complicated secrets they hold.

Eric Davidson

Keep on Running: The Story of Island Records

Rush Live Review

Neil Hamburger, Hot February Night

Clinic Live Review

Devo Live Review

Rush, Beyond the Lighted Stage

Pitchfork Music Fest '10 Wrap-Up

Here Comes Your Weekend Parking Lot Blowout Live Review

Tristan Perich, 1-Bit Symphony

Touch and Go: The Complete Hardcore Punk Zine '79-'83

A Live Evening with MGMT

The World Cup Top 10

Five Hundred 45s

Jello Biafra and the Guantanamo School of Medicine and Chrome Cranks Live Reviews