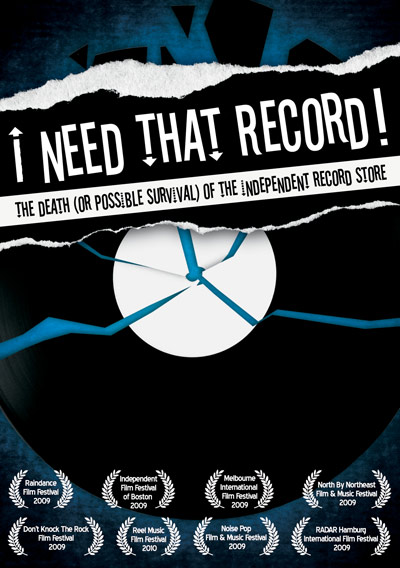

The Death (or Possible Survival) of the Independent Record Store

MVD Visual

Independent record stores have always been special places. There’s a reason why as a teenager, rather than go to the store at the mall that was practically in walking distance, I would save my paper route money and then, once a month, have my mom drop me off at one end of the strip of High Street that ran by the Ohio State campus to spend the afternoon record shopping. Aside from the treasures within, even the stores’ names—Magnolia Thunderpussy, Singing Dog, and Schoolkids, among others—held more allure than the local Record Mart (or worse yet, Record and Tape Outlet, where I worked for a short time).

It is the allure of such havens that filmmaker Brendan Toller celebrates in I Need That Record! With the consolidation of major labels and radio, the rise in price of compact discs, the advent of the internet and the legal and illegal downloading and online retail that came with it, and the loss-leading practices of big box retail, the independent record store has had a lot with which to contend in recent years. For many, it’s been a losing battle; more than 3,000 independent shops have closed their doors in the last decade. That stat should make any record geek worth his 7-inches vow complete allegiance to his local mom and pop.

While Toller focuses on a couple shutterings (Trash American Style in Danbury, Connecticut and Record Express up the road in Middletown), he also looks at the greater importance such stores play in fostering local music communities and breaking the cycle of homogenization. In many ways, the plight of the independent record is indicative of the retail landscape at large, with large chain stores forcing out local character across the country. Noam Chomsky reiterates this fact, drawing a comparison to the advent of supermarkets in the 1930s.

Chomsky is just among an impressive list of interviewees Toller calls on for commentary. From Glenn Branca’s curmudgeonly remark that “we’re not going to be going to stores anymore—of any kind” to Mike Watt’s misty-eyed zen meditations, the film presents both fatalism and optimism when it comes to the future of independent music retail. The latter is lacking to some degree; Toller touches on the increase in vinyl sales of the past few years, but not enough to explain how it may be just the thing to save these shops.

There is one scene, though, that sticks among all the interviews with shoppers, retailers, label owners and other musicians like Thurston Moore and Ian MacKaye. When Trash American Style is finally emptied out, owner Malcolm looks back and comments that it looks like any other empty space. One would never be able to tell that there was once a certain kind of magic that occurred there, one of discovery, shared interests and community. That this film captures some sense of that wonderment is really what makes it worth seeing. However, hopefully, in years to come, it will be simply a curious slice-of-life piece and not a remembrance of what once was.

Stephen Slaybaugh

The Antlers Live Review

Girls and the Wedding Present Live Reviews

The Big Pink and A Place to Bury Strangers Live Review

Jello Biafra and the Guantanamo School of Medicine and Joanna Newsom Live Reviews

SXSW 2010 Recap

Blank Generation

Leatherface, Pere Ubu, and RJD2 Live Reviews

The TAMI Show

The Soundtrack of Our Lives Live Review

Walking on the Moon: The Untold Story of the Police and the Rise of New Wave Rock

Bowie: A Biography

Soul Power

Prefuse 73 Live Review

Best Music Writing 2009