Directed by Celine Danhier

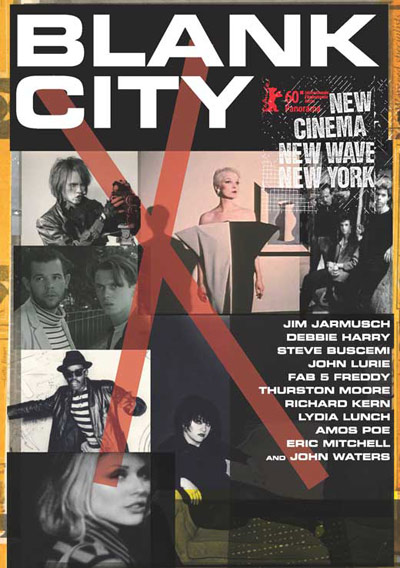

It’s Lydia Lunch’s talking head which provides the summative slogan for the documentary Blank City. When discussing the community of artists seen here, she says that “it was the ugly naked truth as they felt and lived it.” Though director Celine Danhier’s film does an exhausting job time-lining the entire current of New York City’s underground culture during the late ’70s and early ’80s—starting with CBGB’s punk scene onto No Wave and ending with the Cinema of Transgression—Blank City is not so much about the art that was being made as it is about the camaraderie and collaboration experienced between these characters whose passion it was to reflect both the broke desperation and limitless creativity that came with living on the Lower East Side. More than once Blank City’s wide swath of commentators refer to that beginning as a meeting of the minds and to their neighborhood (at the time an endless sea of urban ruin) as the perfect canvas upon which to create. From the outset, Danhier focuses on the scratchy Super 8–shot black and white shorts from the first generation of on-the-fly, off-the-cuff directors like Amos Poe, Vivienne Dick and Eric Mitchell. But as the film progresses the artists reveal that within this movement, the boundary between mediums was non-existent. Everyone was in a band and everyone made art and everyone starred in and helped produce everyone else’s films. In fact, it was Poe’s Blank Generation (depicting the rise and rabblerousing of the Ramones, Blondie, Patti Smith, and Richard Hell) which is credited here as the first real document of this film revolution. In hindsight, it was certainly that cadre of bands who took the spotlight for reinvigorating underground music, but as evidenced in Blank City, it was truly the influence of these filmmakers and their bankrupt debauchery that created far more of an impact in the years to come.

As disciples of Warhol, it was part of the ethos to expose this lifestyle as vivid, over-the-edge, and without ethos. But in no way opposed to the pop art or avant-garde schools, one of the defining qualities of movie’s like Poe’s The Foreigner was that there was no school and no budget. The director’s approach to filmmaking came from an anti-technique, where, as a consequence, bad acting and amateur cinematography was considered a focus on reality rather than a flaw. Building something out of nothing among this un-romanticized apocalypse is eventually what begat No Wave and bands like Mars and Teenage Jesus and the Jerks, who adopted the same un-stylized nihilism of these films and turned it into maniacal rhythmic expressions of the same raw creativity. From Danheir’s perspective, Blank City was the opposite of what we think of when we imagine the pretentious nature of the NYC art forum: it was an arena in which any freak could be a spokesman. And even as uptown Manhattan was starting to clamor for the work of Jean-Michel Basquiat or Cannes was celebrating Jim Jarmusch’s Stranger than Paradise, the artists of Blank City maintained a purity and a love affair with the depravity of their environment. In Wild Style, Fab Five Freddy introduced the world to graffiti, breakdancing, and hip-hop. Glenn O’Brien’s TV Party solidified public access as a channel devoid of censorship where this art could be seen en masse. And the No Wave musicians spawned an entire generation of noise and improv artists (perhaps the most notable being Sonic Youth).

Still, Danheir shows that there was an endpoint. The final third of Blank City details the dark, sometimes gruesome, and almost always sexually explicit films of the Cinema of Trangression, led by the charismatically doomed Nick Zedd. Along with Richard Kern and the aforementioned Lunch, these directors tended to reflect the surreal nature of the Lower East Side’s decline. The advent of AIDS, the influx of heroin addiction, the rapid and forceful gentrification of the neighborhood, all had a hand in killing the vibe quite literally. If anything the Cinema of Transgression films, hard as they are to watch today, not only dealt with the death and despair within the scene, but also grotesquely mocked the culture of celebrity and commoditization of indie film that was squeezing out the last breaths of the NYC underground.

Kevin J. Elliott

Aesop Rock, Danzig, and the Antlers Live Reviews

The Feelies Live Review

Surfer Blood Live Review

The Naked and Famous Live Review

The Walkmen and the New Pornographers Live Review

The Indie Cred Test

The Upsetter: The Life & Music of Lee "Scratch" Perry

Papercuts and Mi Ami Live Reviews

Pere Ubu Live Review

Edwyn Collins Live Review

Lemmy: 49% Motherf**ker, 51% Son of a Bitch

Paul Collins Beat Live Review

The Church Live Review

Tusk 33⅓