King of the Night Time World

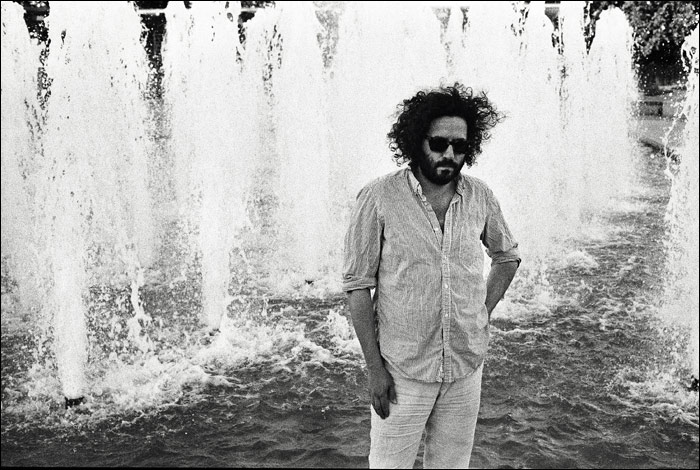

by Matt Slaybaugh

Dan Bejar’s had a hell of a run recently. Since 2006’s freaky masterpiece, Destroyer’s Rubies, he’s successfully sold poetry to the masses while increasing our tolerance for 10-minute songs. His contributions to each subsequent release—not only as Destroyer but with Swan Lake and the New Pornographers as well—have been greeted with ever-expanding fervor, and the influence of his music and his tastes continues to broaden.

Destroyer’s ninth record, Kaputt, continues the trend with another great album, but also takes a sudden left turn. Anyone who missed the Bay of Pigs EP will likely be stunned by the significant changes in the band’s palette. It’s a sound that is hard to describe without cliches about European lifestyles. Suffice to say, ambience takes priority. There’s also probably much more saxophone and trumpet than anyone was expecting.

Shortly after the new year, I was able to reach Mr. Bejar through the wonders of electronic mail. Fans of his tightly packed lyrical conceits will find his comments pleasantly confounding.

How do you describe your goals with this album? Are you moving toward something? Away from something else?

Dan Bejar: My goals were to make something people could talk over and to condemn said conversation. I think I’m moving towards something, yes: varying points on the spiral, becoming a real singer, less about the song...

Was the relative lack of openness of the song structures a goal or just the result of the process?

DB: Not sure exactly what you mean. Unless “openness” means “song structure,” in which case I totally know what you mean. What there isn’t a lot of is verse chorus, verse chorus, bridge, verse chorus, outro-fade, etc. That being said, it was all played on a grid—maybe that’s what you mean—and the grid was definitely the result of the process. It practically was the process! The lack of traditional strong structure in the bulk of the songs was just a result of me completely losing interest in sitting down and writing songs. So I went out of my way not to learn the songs, just follow the lyric cues, the vocal turns. It’s not the first time I’ve done this, just the first time I’ve done it so much. “Looters’ Follies” also springs to mind, though everything about that song rages against the album we are talking about here.

Everyone assumes that a new record that sounds differently from the last one must be the result of accumulating new influences. Is that the case?

DB: Maybe. I think on Kaputt it’s dusting off real old influences and also digging into instrumental music more than I ever have, specifically some new age ambient music, sad jazz music from the late ’50s and early ’60s, early free jazz, some movie soundtracks, New Order. So yeah, it’s half the case. If I could use a musical instrument to do anything besides just string together chords, I’d probably find a sonic voice I could commit to for life. I would prefer that. I would feel more confidant in the world of music. But as it stands, I’m at the mercy of all sorts of whims.

Have you been listening to a lot of ’80s music and European pop or is that just a coincidence? Or is this just the result of the band’s work together?

DB: I didn’t listen to ’80s music so much as think about the music of my teens, specifically when I first really started getting into music, before I gave a shit about lyrical matters. I would describe that era as 1985–1991, and it generally predates any real interest in American rock music, aside from Dinosaur and Galaxie 500 in my late teens. I started off kind of John Hughes-y, aside from a Psychocandy obsession, then got really into Manchester and then seriously into shoegaze. Then I heard Slanted and Enchanted and Sebadoh III and I pretty much closed the door on England for a few years. I think about European pop when I think about spending summers on the Costa Brava, hanging out with my cousins in Spain.

Do you give conscious attention the question of craft? Are you trying to “improve” as a songwriter? What would that mean? Is that something you worry about?

DB: I think about craft all the time, for years now—ever since I abandoned craft nine years ago. (I picked it up again briefly for the sake of an experiment being conducted, not for the sake of making a better or worse song.) I think to improve as a songwriter is to worsen as a writer and a poet, which is what all writing should aspire to (poetry). But I sometimes question this stance, which is good. To improve as a songwriter means nothing, the only thing that you can improve at is singing. That feels like a lifelong labor. And the act of recording, and the way things sound, and the way they are played, and the way two or more sounds fight each other. This is the work. An amazing song can suck shit so easily.

You’re somewhat renowned, one might even say notorious, for the ambition and density of your lyrics. Do you have any advice or other comments for those folks spending their Saturday nights trying to decipher the poetry and trace all the allusions?

DB: I don’t understand how reading poetry and reading a map is supposed to be the same thing, unless a map is supposed to be intoxicating. The words should have a physical effect on you, just like the music. I have no memory of ever consciously trying to allude to a single thing. In fact, if I’ve ever tried to do anything, it was to cut off all allusions to anything. Trouble In Dreams was the apex of that, probably the lyric sheet I’m proudest of, but the singing I’m least proud of. Kaputt is the opposite. Never try.

Somewhere you mentioned that Kaputt was influenced by Miles Davis’ 1980s albums. What do you find most gratifying about Miles’ 1980s work? Could you pick a couple of key tracks for people trying to understand the appeal of Mr. Davis’ late period?

DB: Well, I never said this. A press release said it. But I will say that the only words of guidance we gave to anyone playing on Kaputt were when John (Collins) and I told JP (Carter) when he was laying down trumpet on one of the songs to steer into an ’80s Miles feel—and then he actually did! But really, I think if John was being honest, he’d admit to being way more of an ’80s Herbie Hancock fan. When I think of ’80s Miles, I just think of that Siesta movie, and some of the more sublime turns of phrase in his “Human Nature” cover.