Gods of Thunder

by Stephen Slaybaugh

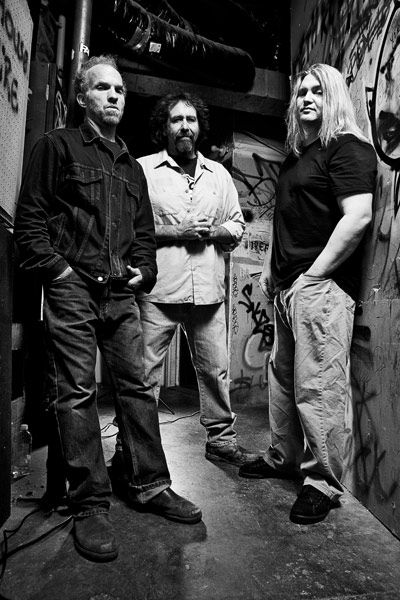

Since forming in Raleigh, North Carolina, in 1982, Corrosion of Conformity has stood at the divide between punk and metal. As evidenced on the band’s breakthrough second album, 1985’s Animosity, the band’s fierce attack borrowed from hardcore, thrash, classic metal—whatever influences seemed fitting—with little regard for genre distinctions. This liberal approach has become all the more apparent over the years as the band has explored a variety of directions as members have come and gone. While guitarist Woody Weatherman has remained in the group throughout its existence, bassist Mike Dean left the band from 1987 to 1993, and drummer Reed Mullin was absent from 2001 to 2010. At the same time, a number of other musicians have entered and exited the ranks, most notably Pepper Keenan, who joined COC in 1989 to sing and play guitar. But with Keenan becoming increasing busy with his other band, Down, Corrosion of Conformity has returned to its core of Weatherman, Dean and Mullin—the line-up that created Animosity.

It’s hard to argue with the results on the band’s self-titled album, which was released at the end of February by Candelight Records. The record is mean and lean like the line-up that made it. As such, it’s easy to compare the album to Animosity, but while it bears a similar ferocity, Corrosion of Conformity also incorporates the many lessons learned over the years into an amalgamation that hits with full force. I caught up over the phone with Dean, who was relaxing in Raleigh between legs of touring, to discuss the band’s then-and-now.

What was the idea behind going with a three-piece line-up? I understand that Pepper having other things to do instigated it, but was there a particular reason you didn’t get another fourth member?

Mike Dean: Yeah, basically the reason we’re doing it as a three-piece is because Pepper is really involved with Down. We had been waiting around to do something with him, but it never occurred to us to get another member because we spent a good chunk of time back in the mid-80s as a three-piece. That line-up had a good track record, and we thought we could do something new and interesting in that format. The smaller ensemble is more concise, and while it’s true that when you perform the material live you will have a sparser arrangement, the elements in that arrangement will be clearer and more featured. That’s how it has turned out and it was a good move.

I know you and Reed had been playing together outside of Corrosion of Conformity, but once it was the three of you again, did it feel particularly familiar?

MD: Yeah, it was definitely very natural and wasn’t like it had been a long time, even though it had been.

Playing live with this line-up, do you guys only do songs that all three of you were involved with recording originally?

MD: No, not necessarily. We dabble in a few songs from Deliverance and even occasionally play “Vote with a Bullet” just for fun and to toy with the audience. We do the song “Deliverance,” and I think every person that was ever in COC wrote a part of that. I just happen to be the one who sings it. But for the most part, it’s material from Animosity and Technocracy or it’s brand new material from the new record.

The way this record has been promoted is as being by the line-up that made Animosity. Do you see a relationship between that record and this record?

MD: Originally when we were talking about making a record as a three-piece, the idea was that Animosity would be the basis and the jumping off point. Once we started putting music together, though, we wanted to be true to being in the moment, and the music we came up with was quite a bit different. But it was inspired by and informed by Animosity because we had learned to play those songs again for some live shows in 2011. That got us dabbling with faster temples and trying to make that much noise with just three people, but the record branched off pretty far from there. Still, I think if you listen to it, you can tell it’s the same people a few decades later.

Back when Animosity came out, there were clearer divisions between what was “punk” and what was “metal”...

MD: Not to us!

Yeah, that’s my question: did you think of what you were doing as one or the other or were you very conscious of the fact that you were blurring the lines?

MD: We were pretty conscious of it. I mean, we thought of it all as just music, but we were aware of the little genre and sub-culture divisions. Those things were silly because it was all just music to us and we just liked a lot of different flavors. It was fun, though, because you’d get people talking and complaining. I guess we were kind of attention-driven and that type of attention was rewarding our behavior so we continued to indulge in it.

I think I first heard you on a Thrasher comp. Do you guys still skate?

MD: I can’t really skate too much. The ankle on the board gets a little tired. But I was never really that good to be honest. I was a little shy to get out on the ramp. But getting some hard wheels and going down hill and doing a powerslide to save your life before you go out into the intersection was more my kind of thrill.

Where did the skull insignia come from?

MD: It was an idea that I had as an iconic hardcore/metal thing. I couldn’t render it, so we asked a friend of ours to draw it. He did it pretty much as described and added his own flair to it. We had an early song that was called “Poison Planet,” which had some good 1980s nuclear war scenarios, and it seemed to sit with that. That design took on a life of its own, and it was almost as key to people knowing about the band as making good music.

Any particular reason you decided to self-title this album?

MD: It is mostly because we had gone for a long time in a configuration with Pepper doing much of the vocals. He was perceived by the public, and especially by people in the business, as being the brains of the operation. Pepper made some great contributions and his contribution is still felt by us even when we’re not playing with him, and people thought that we weren’t going to have a good album in us reverting to a three-piece. We were anticipating some skepticism, even though to us we were reverting to the origins of the band and it’s just as real if not more so. So we wanted to come out with two middle fingers blazing and make a statement that if we are going to make a record it’s going to be a defining work, like this is COC and we’re not going to coast along and make a record that rests on our past laurels or exploits the name. We’re going to do something creative and new, and do our damnedest to make something worthy.

Do you ever worry about confusing your fanbase with the way the line-up has shuffled around over the years?

MD: I think a little confusion keeps it interesting as long as you’re keeping the quality up. And we do what we’ve got to do to make that happen.

In that regard, as far as creating the music and songwriting, how do you keep that consistent? Has there been consistency with people coming and going?

MD: With this latest record, while it stands on its own as a unique group of songs, you can see stylistic tendencies that go right on back to the beginning. There are certain devices that we jumped on as kids that you can still hear in evidence in this new stuff, just maybe a little more refined.

But the group has experimented with several different styles in its own way. I think the most dramatic shift happened when I was out of the band, when they met up with the producer John Custer and did the record Blind, which incorporated a lot of crazy classic rock influences. It might have surprised somebody who heard it, but it didn’t surprise me. Back when I was in the band and we were driving around touring with Bl’ast or whoever, we were listening to Deep Purple and Thin Lizzy and stuff like that. It just took awhile to incorporate those influences into the sound. Once they met Custer and had Karl (Agell) singing, they were able to take hold of that and utilize it. I was pretty impressed with that record.

Would you attribute the different styles of each record purely to the different personnel or were there distinct intentions going into each record that made them come out differently?

MD: Most everybody concerned over the years was drawing primarily from the same broad set of influences. When we made In the Arms of God, the idea was to do something diverse and psychedelic—that was intentional. For this one, the intention was to do faster tempos and reinterpret Animosity. With Blind, I’m sure it was deliberate to integrate the classic rock influences. So there’s always a fair amount of deliberate intentions at the outset, but that’s not always how it turns out because we’re not that good at being calculating.

You mentioned In the Arms of God. It’s been seven years since that record. Was there ever any question that you’d make another COC record?

MD: It was definitely a question mark. For me, it was about whether it felt right. It’s not one of those things you can wish into existence. If it was going to to happen, it was going to happen. If you’re lucky enough to get the opportunity, then you have to roll up your sleeves and get to work.

Do you feel like having these different permutations of the band has contributed to its longevity?

MD: Yeah, probably. It’s hard to get burnt out on a story if you’re still figuring out the plot. It definitely adds interest. It has for us because it’s not the same grinding repetition as it might be if we were married to a formula.