Motor Away

by Stephen Slaybaugh

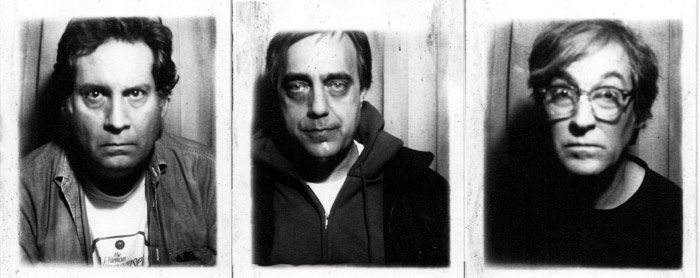

Since forming in Boston in 1987, the Cheater Slicks have spent the last quarter century refining a murky take on the kind of primordial rock & roll equally informed by bluesy primitivism and punkish fuck-all attitude. In their early days, the band featured the Real Kids’ Alpo Paulino then GG Allin’s brother Merle on bass, but eventually guitarists (and brothers) Tom and Dave Shannon and drummer Dana Hatch figured out that the instrument was entirely unnecessary for the greasy sounds they were creating. Throughout the ’90s, the band issued a handful of records for lauded imprint In the Red—including the Jon Spencer–produced Don’t Like You—each one showing the trio’s idiosyncratic ruckus growing tighter.

By the end of the millennium, the band had relocated to Columbus, Ohio, where their output became more sporadic if no less potent. After 2002’s Yer Last Record, they parted ways with In the Red. In the subsequent years, they released only one “proper” full-length, 2007’s Walk Into the Sea (Dead Canary), though they issued the improvisational Bats in the Dead Trees and a couple live records, while their shelved first album, Our Food Is Chaos, was also recently reissued. With a new album waiting in the wings, the Cheater Slicks were ready to celebrate their 25 years of noisy existence when Hatch suffered a heart attack. However, as they say, what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger, and with their new album, Reality Is a Grape (Columbus Discount), clearly being one of their best, the Slicks seem poised for a resurgence. I caught up with Tom Shannon, whose been working on getting his Master of Library and Information Science degree, on the phone to talk about everything that went into the band’s new album.

How’s Dana doing?

Tom Shannon: Dana is doing incredibly well. The lasting effects were almost nonexistent in terms of permanent damage, and he’s bounced back really well. He’s got more energy than ever and is taking his health more seriously. For a terrible situation, it worked out as best as it possibly could. He’s lost a lot of weight. It was more than a wake-up moment—it was much more serious than that. It’s a genetic thing with him, and he had a procedure to open up the arteries.

And he’s back to playing the drums again?

TS: Yeah, I couldn’t believe how quickly he recovered! The first month was rough, but after he got over the initial complete exhaustion, he made a really quick rebound and we were doing shows six or seven weeks after his heart attack. We went down to North Carolina and Atlanta and did some shows, and we’ve played quite a few shows up here. His drumming has been more energetic than ever. It’s been really good. The things they do now are amazing.

It sounded like as far as the scenarios of having a heart attack go it was the best possible.

TS: The main thing in his favor was that he had the heart attack in the ambulance so they were able to immediately make sure there was no damage to the heart, and they got him to the hospital very quickly and did the procedure. The heart wasn’t deprived of oxygen—which isn’t to say it wasn’t an extremely serious situation—but it was good timing.

You guys were supposed to do that show with the Bassholes...

TS: Yeah, that was four days after. It was really a hard thing. I went down to the show, and at that point we didn’t know how Dana was going to be. We knew he was going to be okay as far as it wasn’t something that was going to kill him, but we didn’t know how he was going to rebound. It was an odd feeling to have that planned.

That was going to be my question: did having that coincide with this event to celebrate 25 years of the band change your thinking at all? Did it reaffirm the band or make you question doing it?

TS: It’s strange because we had recorded the record already. It was all mixed and was sitting ready to be released, so you don’t get any sense from the record that we were slowing down. We haven’t been. Dana had been given some warnings from doctors before that he needed to straighten up in terms of diet because he had this genetic defect and it was something he had to watch. We didn’t give it much thought in our daily goings-on, but when I heard he had the heart attack, I wasn’t completely surprised. So especially at that show, I was very doubtful and I was having a lot of anxiety myself about everything. When something slaps you in the face that hard, it makes you think about a lot things and kind of freak out. Since then, it’s not like we are suddenly going gung-ho, but we are definitely grateful that we are able to continue. We would have ended the band if Dana couldn’t do it because it wouldn’t be the same thing. Now that we know Dana is doing well and David and my health seems to be fairly good, we’ll squeeze a few more years out of it. We still really enjoy playing music—we always have. We never lost the passion for playing together. We haven’t always wanted to go out on the road and those kinds of things, but playing together in the basement every week, doing a few shows around town and out of town, and writing songs, we still have a lot of enthusiasm for it.

Did you think the band would have the longevity that it has when you started?

TS: This band has always had a weird feeling about it, so yeah, I did have the feeling that it would last a long time. We enjoyed what we did so much and had a strange chemistry when we played. It’s always felt like there was more to be expressed than what we could do at any given time. I don’t know how to say that exactly. It’s like we were always at a level in our playing that we felt like we could somehow get better or do more. I think that’s important when you are in a band for the long run: you have to feel like there are some ideas ahead still to pursue. That’s always kept us motivated. There’s miraculously always something that takes shape into a record. It’s slower now than it used to be, but that’s no problem.

Do you feel like you could have made this record 10 years ago or 15 years ago or 20 years ago, or is it always that one thing leads to the next?

TS: It’s always strange how they come about. This one was done in the midst of so many other things going on in our lives that we had to squeeze it in here and there. We did a lot of work before I got into school, but once I got into school, my first semester I was completely overwhelmed and could barely do any band stuff. Once we continued with the process of recording the songs, we did different sessions to see how we were progressing with the songs. Those sessions were done with Adam (Smith) at the studio, and we’d basically do a whole studio record as a demo version. We did that two times before we came up with the final versions of the songs that we used. It wasn’t like we were slaving over them, but there was a long passage of time in seeing how they evolved.

How long ago did you did those demos?

TS: The first one, if I had to guess, was May 2010, then we did another session in 2011. The final versions were done early in 2012, then we slowly did overdubs over the summer. So it was three years of going through a recording process, and that was after two or three years of practicing the songs in the basement before getting to that first stage of recording. And that first recording was doing the songs instrumentally with no lyrics or vocals. It was a long process. It’s funny for a band who sounds so loose and improvisational, our process is just the opposite. But because our band is so chaotic, it takes a long time to hone it down into something listenable.

Was that process dramatically different than making, say, Walk Into the Sea?

TS: Walk Into the Sea was completely different. Where everybody was in their lives—Dana just had kids and David was getting involved in a serious relationship—I worked a lot on that with Will Foster alone. We recorded it as a joint effort, but when it came to the production work, it fell on my shoulders. This record was more of a complete group effort, but in terms of how we go about writing songs, it was about the same. Actually, that one was kind of the same in that we did many, many recording sessions until we got one that we thought was good. Will would come over and set up in our basement, and we’d record something then reject most of it. It’s pretty much always been the same since we’ve been in Columbus. When we were in Boston, it was completely different. In Columbus, there’s a feeling of cooperation with the people you are recording with, whereas in Boston it’s all business and you pay by the hour. I think it’s helped a lot to be able to do the demoing to get closer to what we have in our heads.

I read an interview with you online where you were talking about songs forming out of the aether and you guys being conduits...

TS: Yeah, that’s a cliche that a lot of people say about creativity, but that’s truly the case. With writing progressions, I have no idea where they come from.

Are things delineated in the band? Are you the conduit for certain songs and Dana is the conduit for stuff he sings?

TS: The way it works is I write all of the progressions. All of the basic foundational stuff comes out of my head, but I never say that I write the songs because they go through a complete transformation when we start to play them as a band. Then, to answer your question, Dana will claim a song that he will work a lot more on and it will become his song. We will divvy them up, then David will work out his guitar parts over a long period of time.

It sounds like the technology used to make the record from start to finish was all old-fashioned analog technology. Do you take a hard stance when it comes to the analog versus digital debate?

TS: No, I don’t take a hard stance because people have to do different things to achieve what they want in the studio. But I will say that I’m not crazy about the sound of digitally produced records, especially on the high end. There are people putting lots of money into digital production, but I don’t think anyone likes that. It’s not an interesting sound, especially not for a band that’s raunchy like we are. After working on some of our reissue projects, Adam had the idea that he wanted to make us sound more like in the early ’90s, pre–Jon Spencer, when we were doing things on our own in little studios and it was all analog because there was no digital at the time. One big difference with this record was we did very few overdubs, so it’s us playing raw, which he was interested in getting us to do. As far as the analog thing, it was mainly because he had the equipment there and Musicol was there. On the other projects we’ve done with Adam, we’ve used digital here and there because you have to sometime to transfer things. Obviously, the album had to have been digitized at some point because it’s on iTunes. I don’t even know how he did that! But we mixed it down to 1/4-inch tape to make it heavier and dial it up to the point of being saturated. Then Musicol did a great job mastering it. Even the cutting lathe there is not digital, which even when doing vinyl isn’t the case a lot of the time. Vinyl is the unit that we sell so we might as well as make it as pure as we can.

In terms of the songs, it seems like you are working in terms of extremes. If you listen to something like “Jesus Christ,” it contrasts sharply with, say, “Current Reflection.” Was the intention to mix it up?

TS: Yeah, we always try to put a lot of different types of songs on a record. We’ve always been that way. We try to do things that are ballet-oriented, things that are really heavy, things that are blown out, things that are less noisy... I don’t like records that are one-dimensional in terms of sound or song-style. Lyrically, it takes us awhile to write songs because I don’t like the lyrics to be always the same or cliche. It takes time to find what the song wants, and again, sometimes it comes to you out of the air. With “Jesus Christ,” Dana had written the lyrics to the song and I had this one thing I wrote one day, and we combined them and it worked out really well. It wasn’t thought out at all; it just happened to fall into place.

Did doing the Bats in the Dead Trees record influence this record at all?

TS: Yeah, that was a really good thing for us to do because afterwards we played differently. It allowed us to loosen up to a certain extent and be able to stretch out more than we allowed ourselves before. Now we can go off and be wilder in the studio than we had previously allowed ourselves to be. I’m probably more rigid than the other guys and it was good for me to be able to let things fly and not worry about it. That record helped point us in a new direction and when it came to writing the new songs, we were able to let them remain loose for awhile without worrying about their structures. It was a good break. You can be accused of being overindulgent for doing something like that record, but we always had an improvisational aspect of our music. It allowed people a glimpse into that part of our process. I couldn’t play any of those songs now. They were improvisations. We did play them once live, but we haven’t played them since then and they won’t be played again. It was an exercise, really.

Do you think people have certain expectation for Cheater Slicks records?

TS: I am always confused about how people view our band and what they expect from us. I’m very happy by how this record has been received. For a Cheater Sicks record, it’s selling pretty well. It seems like our profile has come up a little bit. Maybe it’s the internet. The internet is good for a band like us because our stuff is hard to find. Now people can stream songs to hear them, whereas before it took some effort to hear one of our records. People seem to respect us for what we’ve done for so long and the purity we’ve kept to it. I’m happy there’s enough people out there to allow us to feel like we’re not playing in a complete void. From about 2000 to 2008, we felt like we were playing for ourselves. There was no problem with that, but leaving In the Red set us back. Maybe that’s what needed to be done, though, as it drove us in a different direction. Everything had a set pattern when we were on In the Red. When that was disrupted, we decided to be completely ourselves, and I think it worked out well.

Yer Last Record was your last record on In the Red. Did you know that was going to be the case when you titled it?

TS: No, I did not, and it wasn’t until a couple months ago that I realized it. None of the things we ever do are premeditated. Of all our records, that was the most difficult to make. It was a really bleak time. David Katznelson came out and he was having a rough time, and the songs were really heavy. That’s a strange record. It was so bleak—that’s why we called it Yer Last Record. We thought people would play it and commit suicide.

It’s like the lyrics of “Current Reflection.” It’s all about this guy who is falling apart and his lips are bitten raw and his eyes are bruised. I looked at the cover of the record and realized that the guy on the cover is a complete reflection of that song. David had that photo from an old TV show. Even specifically in the lyrics it says, “I raise my hands to my lips,” and he’s raising his hands to his lips. That’s weird stuff that I don’t know how it happens. Maybe it was subconscious, because your mind relates to certain patterns. It wasn’t premeditated, but then that’s an exact replica of the lyrics.

You were talking about making music for yourself. Then or now, what is it that motivates you to make music? Is it just a desire to make art?

TS: I really do think that’s what it is. Self-expression is a part of it, but it’s mainly a drive to make something. That’s how I view it: it’s an ongoing, evolving pursuit to make something, and until it feels like there is no evolution left, we’ll keep doing it.